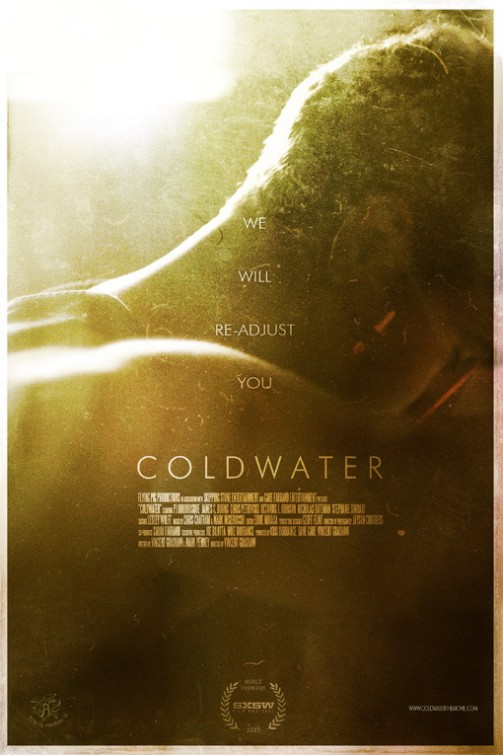

Something within writer/director Vincent Grashaw led him to come back to his passion project from high school. He wanted to tell the story of juvenile correctional camps, and it kept pestering him. Eventually, after he broke onto the scene after producing writer/director Evan Glodell‘s Sundance breakout Bellflower, he moved forward with what was to become Coldwater, which premiered at SXSW earlier this month.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Grashaw, his stars P.J. Boudousqué and James C. Burns, and executive producer Joe Bilotta shortly after the premiere. Together we chatted about whether they had the chance to cast named actors instead of the mostly unknown cast, the casts expectations going in, whether they went back to the Bellflower investors again, the pressure of submitting an unfinished work to a festival, and much more. Read the conversation below.

The Film Stage: Dealing with juvenile boot camps and rehabilitation, one of the things that I’m curious if you looked into was how medicine can help a lot of people and if you diagnose, especially early on, you can get a pill for it. Can you talk about that research?

Vincent Grashaw: Off the bat, in terms of medicine, I’m not most qualified person to talk to about that. I do know a lot of people growing up that were on medicine whether it was anti-depressants, and those kind of things can be dangerous and prescribing kids those kinds of things so young because then you’re pretty much dependent on it. To me, I don’t know, it seems a little dangerous. I think that conversations of kids and mental health is a huge thing going on today; it takes a lot more than just trying to think of a pill or one solution to handle everybody. It’s more of an individual process and a lot of care and attention you know. It’s not easy to solve and that’s why the problem is such a big issue. There’s no easy way to solve it.

Vincent Grashaw: Off the bat, in terms of medicine, I’m not most qualified person to talk to about that. I do know a lot of people growing up that were on medicine whether it was anti-depressants, and those kind of things can be dangerous and prescribing kids those kinds of things so young because then you’re pretty much dependent on it. To me, I don’t know, it seems a little dangerous. I think that conversations of kids and mental health is a huge thing going on today; it takes a lot more than just trying to think of a pill or one solution to handle everybody. It’s more of an individual process and a lot of care and attention you know. It’s not easy to solve and that’s why the problem is such a big issue. There’s no easy way to solve it.

P.J. Boudousqué: I also think there’s a stigma behind it today related to youth. A lot of times you know you don’t want to address that there is a chemical imbalance or something or innately unbalanced or wrong with you. Parents often mistake acting out with just lack of structure and lack of respect and really there’s an underlying issue. I feel like sometimes parents have concern, they paint with broad strokes and they often don’t think therapy will fix it or maybe that’s just not enough or maybe they have the wrong therapist or they need to address to the medication. So because of that they’re more compelled to send someone away, that’s who can take care of you.

Joe Bilotta: I think it’s really important in this particular context that everyone understands that we’re not preaching with this film, and we’re not trying to set examples with this film. We took a cross section of everything that they just discussed, everything from in and out of control children to possibly chemically imbalanced children to hazing situations to the Peter Principle and even explored the fact where someone’s promoted beyond and we wrapped this all into a big bow with a really pretty picture and great music and great acting; and we put forth not a message film but just an entertaining feature that could leave you with a thought provoking issue in the back of your own mind of something you had to deal with.

I know when you went ahead and came out with Bellflower at Sundance and all of a sudden it took off, I can only imagine that you had a cut of that film ready well in advance of Sundance, correct?

Grashaw: Uh, no not necessarily. We basically submitted them a rough cut and I would say it was a couple months later when we found out we got in and in between that rough cut stage and when we got in we were probably in the darkest place making that movie. We were just in a big hole: we had no money, we didn’t know how to finish it and we were at a place where we loved it but we really didn’t know what to do with it. Then it got in and we obviously rushed to get it done for the festival.

I’m curious about that process, since its so different from the Hollywood studio system. They’re financed, they’re set with a release date and you make that release date. Nobody has to approve of it necessarily out of context. It’s finished and then it gets released. Whereas you’re submitting an unfinished product and coming in with a finished product. How scary is that to know and how much does it give you confidence because when you get accepted all of a sudden it’s like, “I can do this so much better”?

Grashaw: I mean, to be honest, the festival should be scared more than us when they do that because they don’t know what you’re going to come with if they saw a rough cut. They’re assuming the rough cut that you sent is going to be cleaned up if not come out better which in Bellflower and in this, it definitely came out a lot better. We had the time, this time around, to actually go through the process of the mixing and all of that. We were never really pressed for time but it came down to the wire to get it out here in time for them to screen it. Yeah I don’t know how much it scared us because we already had that stamp of approval so we knew we were on the right track just from being accepted it was like, “ OK, now we just got to get it done.” Even then it’s not done until the distributor buys it and puts it out, so there’s notes there and you still make changes, if not then it’s picked up and released. It depends who wants your movie.

Bilotta: But in regards to this film, what we submitted and what you saw on the screen was just the same thing but just—the music was surround sound, and all the colors jumped off the screen because we were fortunate enough to shoot in 5K on a RED camera. So you look at the woods and the colors and the trees and the skin tones. We got to do that after we had submitted the film.

Grashaw: Yeah we managed to submit it and cut it down to picture lock but not color or mix or anything. That process happened in about a month and a half. We had to get all that done which is not horrible, it’s a good amount of time.

With Coldwater, I know you did some interviews before the film was even a finished product. How interesting is it to have no interest, with press asking you about, “Hey, what’s coming up?” to all of a sudden, “Oh, I have to give an answer for that”?

Grashaw: Yeah. You know I think kind of, in a way, when Bellflower happened you’re almost invited into a community where people are actually interested in knowing what you want to do. I think with all filmmakers and actors you just want work, that’s kind of like the dream all of us had you know in all of our careers, we just want to work and do good stuff. It’s nice to have people that want to know what you want to do. More people want to get involved like when Joe came on he saw what I’d gone through in Bellflower and he was definitely interested in talking to me and reading the script and then therefore this is why the movie was made.

Did you have the opportunity to cast people with bigger names because of how big Bellflower became and how big that conversation was? Because I know you did a lot of unknown casting and it seemed like you wanted to kind of almost stick to that.

Grashaw: That’s actually a good question. I mean we definitely could’ve made this movie with names and we could’ve made another movie with names but the fact that we were going to move forward with this, I think we all really felt that it was important to keep the cast unknown so we can focus on the reality behind the movie as opposed to just seeing huge stars.

Bilotta: As it turned out, we have huge stars, just people don’t know them yet.

Grashaw: Good way to put it. But yeah the opportunities are there now, other features down the road it’s nice to be able to reach out through agencies and people you meet at these festivals. You actually meet the talent, the stars out there that you can actually communicate with and will listen to you, talk to you.

For you all, you’ve gotten involved in this process with coming up from Bellflower and it’s such an intense, very visceral film. What did you expect coming into this and what was the difference or maybe, was it pretty much what you expected?

Boudousqué: It’s interesting because I remember, it was probably a year before I auditioned for Coldwater, I read an article I think L.A. Weekly about Bellflower. It was showing at the theatre on Olympic and I thought, “Oh that sounds fascinating I want to check it out,” but I never did. Then I auditioned for this and after I booked it, I didn’t know anything about Bellflower or the cult acclaim that it had. I started picking up the pieces when I started working with these guys and talking to Vince and then meeting Evan, who did some stuff with the movie in terms of special effects, and Joel [Hodge], who did the EPK, was the cinematographer for Bellflower. When I saw it, I mean it was incredible. Yeah, I don’t know, it really didn’t have any weight on it until I was already in the midst of really working on the project. It gave me something to kind of – you know like this is a monument behind you and it’s something to be proud of, to be part of this group of filmmakers and I love that about these guys. I grew up playing a lot of punk rock as a kid and one thing it instilled in me was DIY, right? It doesn’t matter how you sound you just have to love doing it and get out there and do it. People aren’t going to make it happen for you, you have to care enough to get out there every day and make it happen; and that’s what these guys do. Really it’s amazing, I’m very proud to be a part of that family. I don’t know. How do you feel?

James C. Burns: About you? I think you’re great. I wish I could hear your punk rock. I have a very strange little career and I work a lot. This came up, we’re in the middle of shooting Call of Duty, which is like a full time job and I had wrote this role off of a wonderful little film called Dangerous Words for the Fearless in Utah for six or seven weeks and then went back in. We met like in April and then I had to go away for the film and then I had to go back to do Call of Duty for three weeks in a row and we barely had a chance to meet. So I really didn’t know anything about Vince until we started talking and he told me he was a hockey player and that sold it for me! I didn’t know anything about Bellflower because I don’t really have time to do that kind of research, not to mention it was my sixth film in the last year. I’m always rolling through things. I just get the script, feels good, let’s meet, I like him but I have work so, “OK, let’s do it!” You know, when you’re working you can’t get outside of that tunnel, you just want to keep working until it dries up. I liked the script a lot, I liked him, Joe not so much. [Laughs]. So I ended up just out of the sheer momentum with what was going on, again like they said in interviews, this role is sort of like a next extension of Woods from Black Ops II. If Woods got a promotion and retired this is what he would be doing. So it was like, “Wow that’s really creepy.” Oh, and his name was Frank. Frank Woods, Frank Reichert, you know what I mean? It’s just so many little nuisances. This is going to be great.

Boudousqué: Does that actually help you set into another character? I mean similarities in terms of names on a basic level, just being recognized as that.

Burns: Well what was great was you guys started calling me Colonel as soon as I walked on set, “The Colonel is here.” “Yeah he is motherfucker, that’s right the Colonel is here! Look out, let’s roll, the Colonel is ready to go!”

Boudousqué: Yeah, I think everyone shit their pants his first day on set. We had shot two and a half weeks before we started shooting him and there was all this anticipation because I mean everyone read the script and knew that he was this key role and they’re like, “What is this guy going to bring? What’s he like? I don’t know.” Literally, James walked in kicking the door down, it was unreal.

Grashaw: To your question about Bellflower and Coldwater and the differences, as a filmmaker I’m not like, “Oh I’m only do it yourself and down and dirty and f*ck the system.” I think the difference is you can thrive to find great results from the do it yourself, down and dirty. You’ll get great results because everyone is very passionate and obsessed with that product at that time. With a film like this, you’re put in an environment where its’ like, there’s deadlines and there’s rules and you follow them. There’s a structure that has been going on forever, like all the union rules and shit like that and put them in an environment. As a filmmaker, I had our composers and an editor on set, editing the film while we’re shooting. I mean that is a luxury that if you’re a filmmaker, you don’t usually get that and the movie can thrive because of it.

Burns: In retrospect, now that I know Vince and knowing my own, making Bellflower was his indication if you can do that you can basically do any fucking thing. I was listening to Quentin Tarantino in an interview and he’s saying that he actually wrote Natural Born Killers before Reservoir Dogs. He couldn’t get it done so he wrote Reservoir Dogs to make $20,000 and he says, “My film school was the five years I spent making my first low-budget film, which was not very good because I learned how to make movies and all the stuff around it by trial by fire.” And I had a feeling that’s this experience. When I work with Vince, Vince has got the ability to be magnetic because he has a confidence about what he’s doing and you only get that by basically picking up sandbags and digging yourself out of a hole in these initial levels of business. You can tell when a guy’s done that or someone’s come out of USC and dad gave him a million bucks for his first film. There’s a level of visceral content that is generally added because I’ve done films like that. It doesn’t have the same kind of balls and that’s what he brings with him, Bellflower was his trial by fire and he has a big set of cojones.

Grashaw: Yeah, and don’t ever want to go back to those kind of ways sometimes. I mean, it’s about keeping the family together but also proceeding to the next stop where you’re actually reaping some of the benefits of killing yourself over the last one. You know?

Burns: You kill yourself in other ways.

Bilotta: Part of that is due to me because I met Vince in an extremely roundabout way. Someone that he knew was working, I was managing as a music studio and a lot of composers, so Vince came in and I saw Bellflower and I thought it was wonderful for what it was. I saw Vince’s talent and he gave me his script and it happened to be about—I went to a military college and I experienced hazing and I understood a lot of the personalities and the structure with them. I also looked at it as an opportunity for my people to engage and give Vince something that he didn’t have in Coldwater and that’s this whole musical studio and editing facility that was a cradle for him to go off and do what he wanted to do. So, as a result of it, it worked out so well because he could control the musical environment as well as the visual environment. I think that the film definitely speaks to all of that.

I’m curious because you mentioned how you want to take advantage of the achievements that you basically earned, that you’ve suddenly unlocked and move to the next stage. I’m curious if you went back to a lot of the same financiers that you had with Bellflower and basically said, “Hey! Come on.”

Grashaw: There’s a number on the Bellflower budget but there was never any time where it was like, “Here’s $17,000.” It was like, “Here’s $0.” We’d make money and we’d shoot, we’d make money, we’d shoot and we shot most of it in a block of three months but there was never a budget, there was never an investor. We had a few friends that gave us a few thousand dollars here and there, and then when we got to Sundance we needed to finish it properly that’s where we got more money from friends because it was like, “ OK, now they really need it and here’s why.” But yeah we never had a budget, I didn’t need to go back to them because they were friends and it was like we paid them all back, they were very happy about that and they’re making profits on the movie, so they’re happy. They’re just like, “Holy shit. We helped these guys.”

Yeah. “We’re getting money back? Wow, alright.”

Grashaw: And they came to set a couple times and there was this little camera and it looked so hokey to them because they were just like, “Oh, what are we doing helping these guys?” But yeah, luckily I don’t have to go back to them for money because I wouldn’t do that.

Bilotta: The answer was: I paid for it all.

Grashaw: But for this movie he was our investor.

A lot of people took a lot of interest in the Bellflower car obviously, and a lot of people were actually kind of disappointed that you didn’t create a camera rig specifically for something in this film, just do something that lasts beyond the film itself. The Bellflower car I remember seeing it at Comic-Con if I’m not mistaken, so that thing kind of got around and made the rounds.

Grashaw: Yeah, we brought it here too for that festival. Evan’s a filmmaker that does things that blow people away; that’s why I plan on producing his films because he comes with a vision that I don’t think people have ever seen before including building those cameras that he did and the car and all of that. That’s his niche, I differently like to tell stories more about human condition and the choice that people make and the consequences they have for those decisions, a little more intimate. We’re totally different filmmakers so I wasn’t really interested in doing anything like that; I wanted the film to look beautiful and stand out on its own.

Bilotta: We just can’t carry the camper. The camper is our car.

Grashaw: The flamethrower is mine. But yeah, you know, I guess we’re just two different filmmakers. I don’t know what people expect in terms of building a new camera system, his next movie will have one though and a lot of new toys.

You mentioned how you’re coming into this film and being a very different director from Evan, you all working off of each other and keeping it in this collective group that you call basically your production company. So, what is it that you’re looking for? Have you found anybody that you’re kind of giving a hand to, to maybe get them into a step in the right direction?

Grashaw: As far as other filmmakers? Yeha, I mean it’s funny we’ve been reached out to a lot. Evan and I got an email the other day and it was from a kid that is studying in Florida, actually those kinds of things we love to get. I mean we’ve gotten a lot of those and it would be just a personal email from them and they’ll have a bunch of questions for us and we’ll spend the time doing that because we were there not even that long ago. You know actually one of the kids in this movie who plays one of the lead roles, Nick Bateman, he made a film on his own like down and dirty when he was 19; and he sent us that movie because he saw Bellflower, he had heard of Bellflower and he saw the way we did it and sent us that movie and Evan was really blown away by it and sent it to me and I watched it. You could see this kid was a very talented guy and so when I was casting I couldn’t find this one role and I’m like, “What was that one kid’s name, we watched that movie?” So I reached out to him and sent him the slides and he put himself on tape and we cast him off that. So I think, everybody’s got a place or heart for people who are passionate that aren’t quite there. Film right now, independent film, is changing so much like very quickly where I don’t think everybody knows where it’s going to end because self-distribution, crowd funding, all that is kicking in; where I think a lot of companies are scrambling like how is it going to be. It’s kind of a similar thing to how music changed and it’s great. I think it’s the best time for people who want to make movies. As a painter you have your tools you can do whatever you want; this is the first time for movies that you have all your tools very easily. Yeah you need a group of people but not like you did 20 years ago where you needed half a million dollars easily. Now you can make a movie with 50 grand and it looks great and you have people that will work on it.

Bilotta: Now you say that.

Grashaw: Well intimate in a Bellflower way. But you know what I mean; it’s a great time for independent films.

Speaking on the fact that you had so much success from Sundance with Bellflower and where you’re going now, do you feel that kind of level of pressure to succeed at this festival and any other that you premiere at? Or is that level kind of already been reached so you just know, “I’m working off of what I’m doing now.”

Speaking on the fact that you had so much success from Sundance with Bellflower and where you’re going now, do you feel that kind of level of pressure to succeed at this festival and any other that you premiere at? Or is that level kind of already been reached so you just know, “I’m working off of what I’m doing now.”

Grashaw: One of the things with Bellflower was when we first got into Sundance we didn’t know anything that was going to happen after that, then it got bought and then we found out what our campaign was going to be and then we did SX; it was like a domino. And so from that high went to another high to another high up to everything that happened. I think I always revert back to the fact that that we were accepted to SXSW; that was a homerun for us. Now it’s just reaping the benefits and pushing forth the next step that needs to happen and being familiar with it so I don’t think you should ever look at what happens as a failure though.

Boudousqué: I can’t say enough like how crazy this experience has been. I mean for my first movie I couldn’t have asked for more. I’m from New Orleans; I grew up in Louisiana and I always heard of SXSW as this music festival, this big music city and I never really knew too much about it. I had some friends that played here over the years. It just seemed like one gift after another; just booking the part, obviously in itself, and getting to get to know the guys involved which was just an unreal experience and finishing the film and seeing the work that was being done which was like, “I can’t believe I’m a part of this project.” Then finding out we were accepted into SXSW. As an actor you don’t expect that, at all. So it’s been so exciting and to get here and see what it’s like and to experience this whole festival. I think homerun is a great way to put it. I don’t think Evan, speaking for all of us, could be happier to be here. It’s an unreal experience.

Burns: And we all love barbecue.

Coldwater premiered at SXSW and is currently seeking distribution.