We are carnivores. That’s a proven fact, right? Where a moral code of honor in our interactions with animals existed at one point—and still does in some cultures—the present slaughter of animals for human consumption has become a business. It used to be we made sure to use every last bit of our furry prey so as to ensure its death was not wasted. We’d eat its meat, capture warmth from its pelt, and shape tools out of its bones. Animals were sustenance and survival inside a convenient package it took skill to hunt, raise, or train. With increased technology, however, these creatures have become nothing more than genetically bred, faceless commodities bought and sold without regard towards their individual lives. For many this truth is in need of rectification.

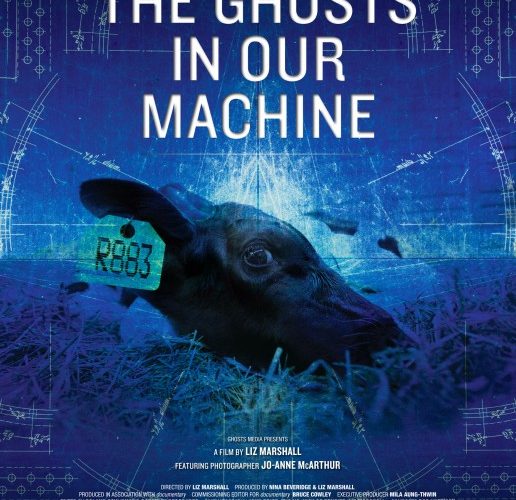

This is where documentaries like Liz Marshall’s The Ghosts in Our Machine come into play. By putting the harrowing images of factory farm-born animals tortured and malnourished on the big screen for all to see, they attempt to tug at heartstrings and our almost nonexistent compassion towards anything beyond our own species so the masses can band together and create change. But where the abuse of mankind is impossible to watch, not everyone finds himself closing his eyes when a cow comes towards them on a conveyor belt to get a captive bolt pistol pressed against its forehead. Our society has been desensitized because we’re ingrained from a young age to believe in our superiority as intelligent creatures. These animals are our food source and will continue to be until they rise up against us.

I’ll admit I’m one of these people. I love the taste of red meat and frankly don’t care enough to find out the details of how it came to be cooked and seasoned on my plate. Does this make me a bad person? To portions of our society, yes. These activists love to inundate non-believers with extreme depictions of violence, pools of blood surrounding infectious animals awaiting their death, and the fear of isolation in these creatures’ eyes through the metal latticework of cages and then wonder why we’ve become numb. They’ll equate the disparity in rights between man and animal with slavery and women’s rights. But while such an easy comparison seems apt in an emotionally generalized sense, it fails since cannibalism wasn’t a factor in either injustice. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t.

In this respect I applaud Marshall and her subject—photojournalist Jo-Anne McArthur—for not going too far into that sort of mind-numbing rhetoric I generally ignore. Instead they take more of a stance based on the ethics of treatment rather than fully resorting to indoctrination of veganism as the one true religion of protein consumption. Yes, it’s intrinsically there when dealing with a ten-year vegan as the film’s star and a place like Farm Sanctuary in New York posting signs to please not consume animal byproducts while on the property, but it’s kept on the periphery. When Temple Grandin’s voice is heard over the imagery to talk about how we need to find a way to give these animals a life whether we kill them still or not, I began to appreciate the film’s goal.

We all know zoos and marine theme parks aren’t the greatest environments for animals to live within. We’re fully aware farms with deplorable conditions are raising foxes and minks for fur or cows and pigs for meat around the world. And yes, America and western nations probably have their hands in the pot. This stuff isn’t new and those who care have been or will be exposed to the concept soon enough. What The Ghosts in the Machine hopes to focus on instead is the identities of the animals. Through McArthur’s still photography and Marshall’s video we are introduced to rescued Beagles and cows with names and faces. They appeal to our natural adoration of cute furry friends to counteract the frightening imagery at the start of those they could not save.

Herein lies my major gripe, though. While I enjoyed experiencing the warfront metaphor of what McArthur endures to capture her images, the film ultimately becomes a story about her rather than them. Billed as a “documentary that illuminates the lives of individual animals living within and rescued from the machine of our modern world”, The Ghosts in Our Machine is actually about Jo-Anne McArthur and her fight. While noble and worthwhile as a narrative, it’s not what we’re told we’re getting. Those eloquent enough to stand by their convictions could argue the film exploits the plight of these creatures for financial gain because while McArthur genuinely does this for the right reasons, moments depicting people telling her she needs to advertise herself more come completely false when remembering they’re in a film about her.

But hey, I’m a meat-eater who doesn’t see any future in which I won’t remain one. So I’m not necessarily the target audience. Objectively, however, while a beautifully produced documentary showcasing a photographer who puts a ton of emotion in her work and truly believes in her cause, I’m not sure the film gives anything we don’t already know. My interest was in the idea of compromising and learning to think about ways to improve the dairy and meat industry rather than dismantle them altogether. I’d love to know the meat I eat comes from an animal raised compassionately. I also like how McArthur uses her work to raise awareness by documenting rather than liberating. The bond she makes affects her immensely and the pain leaving them behind only makes the mission more important.

In the end, though, seeing cows Fanny and Sonny saved by the Farm Sanctuary or watching cute little Abbey the Beagle find a caring home after months of vivisection won’t make me turn vegetarian. Maybe plants have souls too. This subject is rooted in spirituality and religion and the film’s constant look into the eyes of these sad, soulful animals to push that agenda becomes a bit much to stomach without a slight smile at its over-wrought manipulation. The Ghosts in Our Machine tries too hard to be too many things and should have solely focused on McArthur breaking into fox farms and working towards animal rights or solely with meeting saved animals personified by the love given to them. Both concepts compete for attention here and the whole suffers as a result.

The Ghosts in Our Machine screens at Hoc Docs April 28, May 1, and May 4.