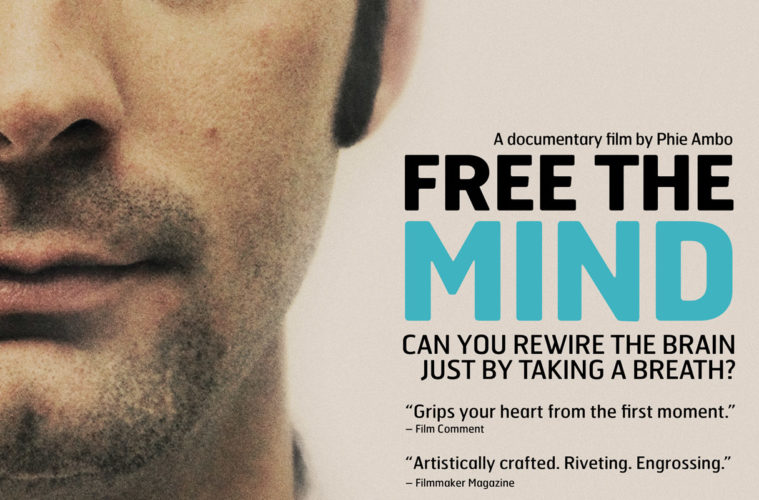

As Richard Davidson states in Phie Ambo‘s documentary Free the Mind, the human brain is the most complex creation in the universe. Here is an organic super computer that handles everything we do, feel, think, and dream and yet we’ve constructed a myth positing how we only use about twenty percent of its grey matter. But while such a baseless statistic may be false, scientists such as Davidson are starting to ask the question of whether or not we take intentional control of its power. No, he isn’t talking about digging into our brain to turn on some switch with which telekinesis is made possible — maybe that’s something a future film could touch on. Instead his goal is to see how compassion, meditation and breathing can help troubled souls rewire how they handle information.

Speaking about the concept of emotional intelligence as a more important tool than the normal cognitive one we teach in school, Davidson’s research seeks to discover a way to control our feelings. He’s proposing that we are capable of achieving a higher level of clarity and emotional understanding to those around us through meditation and yoga. With a team of neuroscientists and “mindfulness” teachers he conducts simple breathing exercises in groups of preschoolers and war veterans. Just as kids diagnosed with special needs like ADHD find it difficult to overcome anxieties and fears about concepts they don’t understand, soldiers suffering from PTSD due to their actions in Iraq and Afghanistan can’t cope with the memories burned into their minds. Meditation looks to provide a way to separate reality from thought by introducing a universal calming technique.

It’s an intriguing idea to say the least and the main subjects partaking in the test onscreen are definitely troubled by what’s happening inside their heads. For three-year old Will the thought of riding an elevator cripples him to tears as breathing constricts and panic takes over. Bouncing off the walls, unable to sit still, and constantly slapping himself in the head for no apparent reason other than boredom and attention, this young foster child turned adoptee struggles with the ability to interact to those around him. And while you’d think it would be hard to compare Will to men like Rich and Stephen just back from the Middle East, they too can’t survive in normal society without pushing loved ones away until their guilt ravaged memories are all they have left.

This is why Davidson has taken on the task of introducing meditation as a secondary treatment to conditions like ADHD and PTSD in lieu of pharmaceuticals. A closeted practitioner of the eastern technique, it wasn’t until he met the Dalai Lama and was asked why neuroscience wasn’t being used to measure concepts like happiness and joy alongside depression and anger that he decided to bridge his passion with his vocation. Seeing the rising numbers of returned soldiers committing suicide, he wondered if he could unlock their torment and alleviate their pain. And if meditation could work to calm them, how young could he go? Herein was the opening to teaching children as well in order to gauge how early the technique could prove effective and whether the effects would last.

Unfortunately for the film, however, the brevity in its depiction of the experiments and nonexistent look at comparison with the control groups makes it hard to blindly accept its success. The tests are only a week and during them we see how Richard, Stephen, and Will cope with their thoughts. It’s easy to throw around statistics that explain the effectiveness of the study, but showing actual examples is much harder. For the Army men it’s more believable as we hear them speak about better sleeping habits and a more conscious understanding of how they treat the ones around them. The breathing does appear to help improve demeanor and attitude as they learn what it means to live again by no longer clouding their thoughts in regret.

It isn’t as simple for Will as the process of overcoming fear is a natural byproduct of growing up. Watching him fidget and not pay attention during breathing exercises makes you wonder if they did anything to help his cause. Showing him snatching a bucket of dirt from a classmate and than the aftermath of a teacher asking whether he feels sad when seeing the other boy cry proves nothing about his compassion. Kids know what they need to say to feign empathy and get authority figures off their back and looking at Will’s face when he says he feels sad doesn’t necessarily read as authentic remorse. With cameras stuck in his face and a ton of attention, I’m not sure the film gives proof his newfound confidence isn’t an act of transformation due to the spotlight.

Ambo’s documentary is a nice story depicting real people overcoming obstacles, but generally glosses over the science with effectively fun chalkboard animations in the process. Delving too far into the human-interest angle, it subverts the work being done to create a more moving cinematic work. Did Davidson’s science help these men? Probably. Does the film provide the evidence necessary to convince me? No. Free the Mind has a lot going for it on the surface—especially with gorgeously atmospheric internal brain depictions similar to the music video for Massive Attack‘s “Teardrop”—but it’s way too cautious about going deeper in fear of alienating its audience with too much scientific jargon. This is the polished and packaged film hoping to captivate the lowest common denominator. I wanted the one a scientist would make for his peers.

Free the Mind screens at Hoc Docs May 2, 3, and 4.