When it comes to sex, things can get real complicated real fast. While the act itself may be dictated by the most primal of instincts, questions of morality, legality, gender, power, not to mention that funny little thing called feelings often ensure that no bodily liquids are exchanged without consequences.

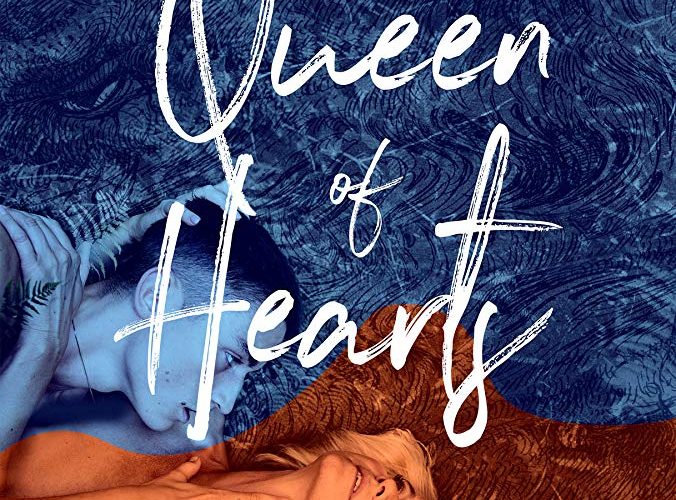

In Danish writer/director May el-Toukhy’s gripping, thought-provoking erotic drama Queen of Hearts, problematic sex happens at an unlikely place. Middle-aged Anne (the ever-remarkable Nordic screen goddess Trine Dyrholm) is an intelligent, compassionate, happily married attorney who specializes in sexual abuse cases. She stands up for young, traumatized girls and defies professional rules of conduct to confront their predators in private. Not only revered by her peers, she’s actually loved by her clients. Besides a prosperous legal career, her success extends to the personal front as well with loving husband Peter (Magnus Krepper) and their twin daughters. By all appearances, this is an exceptionally accomplished woman who’s found fulfillment in life. But then Peter’s teenage son from a previous marriage, Gustav (a breakthrough star turn from Swedish actor Gustav Lindh), enters the picture.

The screenplay, co-written by Maren Louise Käehne, is careful not to build Anne’s transgression on something as simplistic as instant infatuation. During the first hour of the film, she pretty much sees Gustav – a dashing young man with a troubled past – as her husband’s child, a new member of the family. If anything, Anne is tough on Gustav, going as far as to blackmail him into behaving. This refusal to just blame the hormones makes the eventual affair between stepmom and -son all the more compelling.

Of course, an element of desire is there, awoken perhaps by the dates Gustav brings home – audible reminders that this “child” is a full-blown sexual being. But the way the two (female) screenwriters approach (female) sexuality is way more sophisticated than surface-level kicks and kinks. Through subtle hints at a difficult childhood, we get to know Anne as someone who’s had to overcome a lot to be where she is. This explains her discipline, willful character and unforgiving sense of justice. But it also paints a picture of an obsessive, lonely perfectionist. In the words of her husband and her boss, Anne has trouble taking orders from anyone or admitting to her own mistakes. For her these are probably signs of weakness which she’s learned to never show. When this irreverent punk of a kid shows up, however, Anne gets a taste of what it’s like to venture out of her immaculately, tirelessly kept world, and the seduction of risk, danger and not being on top of things 24/7 might have finally proved enough to call her bluff.

It’s awfully refreshing to see a sex-themed movie which not only features older-woman/younger-man dynamics, but puts the woman in the position of power. Despite ageist, misogynistic stereotypes entrenched in contemporary culture, Anne is at no point the more vulnerable party of the story. She owns her wealth and influence as much as those lines on her body. Even when she submits herself in the most literal sense to Gustav – and el-Toukhy makes it a point to communicate this visually via blunt, graphic sex scenes – she’s still unmistakably the one calling the shots. This striking role reversal deepens into a fascinating, un-moralistic psychological profile in the last act, when Anne is confronted with the affair and reacts in a surprising, unsettling manner.

In addition to the sharply female-centric point of view, Queen of Hearts deserves further credit for not dealing in categorical labels of aggressors and victims. Although Anne is positioned as the one who “should have known better”, the film challenges you to pass judgment on her. Did she simply have a lapse of judgment? At what point does that become a moral offence? A crime? You realize while watching the drama unfold how everyday terms like “consent” can be wildly inadequate when applied to such intimate, intricately human matters as sex. What you also realize is how you’ve come to be complicit in the verboten relationship so that, when Anne’s sister hisses “He’s a child” to her in a later scene, it feels like such a violence not just for the hot, barely contained indignation, but how shockingly absurd that statement sounds.

Dyrholm and Lindh are both superb. She delivers yet another utterly fearless portrayal of a flawed, arresting character, leaving herself so physically and emotionally exposed you can’t help but identify (if not agree) with Anne’s every impulse and regret. Kudos to Lindh for going toe to toe with one of the great European thespians and very much holding his own with an intense but completely unselfconscious charisma in a risky role. Krepper is also excellent as the torn husband/father. One of the final scenes finds him shushing his wife in one swift, decisive movement, and the unspoken understanding between them is devastating to watch. The movie, with its potentially scandalous subject matter, wouldn’t have worked without such soulful, truthful, painful performances.

Queen of Hearts, which has been submitted by Denmark for Oscar consideration in the Best International Feature Film category, looks great too thanks to the delicious production design by Mia Stensgaard and Jasper Spanning’s resplendent cinematography. Spanning, who also lensed the single-room claustrophobic thriller The Guilty last year, proves his talent again in a drastically different setting. Working with wide open spaces in nature and an upper-class designer home this time, he captures the allure of secrets in polished, golden frames. Shots of the bright green forest, in particular, are beautifully suggestive of all the amorous folly forever hidden among the woods.

In this sometimes fanatic #MeToo era, Queen of Hearts adds a nuanced commentary on gender, sexual abuse and the importance of truth. It’s a cautionary tale that does not moralize. What it does is taking you on a hot, messy ride and asking you to check if all your easy moral convictions are still intact.

Queen of Hearts screened at the 2019 Filmfest Hamburg and opens on November 1.