There’s something about childhood memories that’s inherently sweet, hopeful—how we saw and remembered the world before we learned about loss and disappointment. Multi-hyphenate Kenneth Branagh’s autobiographical drama Belfast, told through the perspective of his 9-year-old self, has that innocent good cheer in spades. It also touches on the Irish fate of leaving and pays tribute to those who did so in search of a better life. From a formal stance, there’s not much here to blow one away, but the film’s heartfelt sentiments and polished production should have no trouble appealing to the general audience.

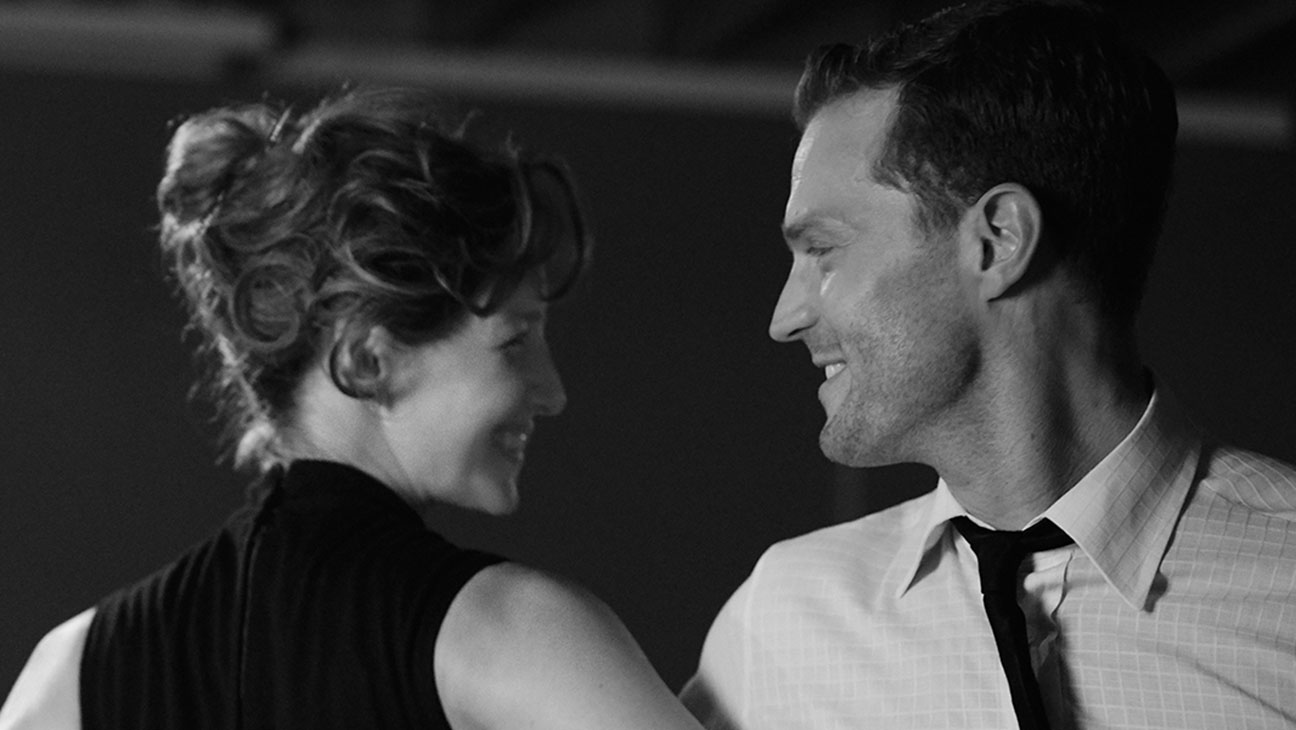

Set in 1969, Belfast takes place in a working-class neighborhood of the Northern Irish capital. The times are simpler: people dance in the streets, kids run around unsupervised, everyone knows everyone. But the times are also changing. Tension between Catholics and Protestants is rising, the economy is flailing, restlessness and frustration fill the air. In the middle of all this is Buddy (Jude Hill), age 9. When Buddy’s not plotting to marry classmate Catherine, he spends his days with Pa (Jamie Dornan), Ma (Caitriona Balfe), Pop (Ciarán Hinds), Granny (Judi Dench), and observes every mysterious thing that goes on in the adults’ world. Why are people vandalizing their neighbors’ houses for going to another church? Why does Ma get sad whenever the mailman comes by with an official-looking letter? Why is Pa saying they should move to the other side of the Earth to start over? Will he have to say goodbye to Belfast, the only place he’s ever known?

Branagh’s screenplay is peppered with cute little anecdotes, like the short montage where Buddy half-cheats his way to better scores in order to sit closer to Catherine, only for the plan to backfire completely. Or his many exchanges with his incorrigibly brash, cheeky grandparents. It also includes many lines that pack true poignancy, for instance Pop telling his grandson about being kept safe by a certain thought. These scenes work because you can tell they come from a real place. The humor isn’t sophisticated but all the more relatable for its lack of design, and the words of epiphany or wisdom feel profound because of how simple, unpretentious they are—like realizations of people who have really lived.

While often amusing, Belfast‘s script only succeeds on an anecdotal level. It’s a string of well-written moments that don’t necessarily add up to tell a good story. It essentially starts with a riot scene that establishes the boiling conflict between local residents of different faiths. But then the subject is dropped for long stretches of time to make room for Buddy’s various pursuits and discoveries. Similarly, the themes of leaving one’s home—of knowing oneself no matter what—don’t seem integrated in the overall narrative enough to gain momentum. Instead, it’s interrupted now and again by interludes that bear little significance outside of being funny scenes themselves. A work like John Crowley’s Brooklyn—obviously very different overall—does a better job sticking to what it wants to say about Irish immigrants.

Branagh’s latest directorial turn is more episodically impressive than wholly successful. When Belfast works, it’s like a beautiful nostalgic breeze or a pang of pure love that goes straight to the heart. There is much to admire in later parts that give Balfe (and especially Dench) more to do––each actress gets a splendidly shot monologue that, yes, very much feels like their Oscar clips, but more importantly communicates such tenderness towards their city that the setting really comes alive. There’s also that shot of Dench behind a glass door in Belfast‘s final scene that’s so expressive and all kinds of heartbreaking.

Outside these truly affecting moments, however, Belfast is often trying too hard to please. We all enjoy reliving the carefree days of childhood, but many of the more casual scenes are so aestheticized and sweetened in tone—complete with a delightful if relentlessly feel-good soundtrack by Van Morrison—they start approximating high-gloss commercials. But what may be my biggest issue is Branagh failing to create a sense of place and time which should be the raison d’être for such cinema of memory. Whether it’s 1950s Taipei in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day or 1970s Mexico City in Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, the viewer feels transported, immersed in an atmosphere entirely its own. In part due to the over-aestheticization, which immediately creates distance, those feelings are largely absent in Belfast.

“Let people enjoy things” has become the most common attack of film critics, and I understand that sentiment completely. That being said, I also think imperfect things can be totally enjoyable. Belfast is ravishing (shout-out to cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos) and endearing to a fault, which won’t––and shouldn’t––stop it from being embraced by moviegoers far and wide.

Belfast screened at Filmfest Hamburg and opens on November 12.