“Paul Schrader’s Los Angeles has changed,” writes Nick Newman in our review of The Canyons, the aforementioned helmer’s first film since 2008’s Adam Resurrected, as well as his first portrait of Los Angeles since 2002’s Auto Focus. Schrader’s relationship with the West Coast is an interesting one: the city played a major role in two of his earliest directorial efforts — 1979’s Hardcore and 1980’s American Gigolo — but it wasn’t for another two decades until he’d return to helm another project set in the film industry nucleus.

In fact, when considering Schrader’s entire oeuvre in the context of setting and locale, the picture one gets is fascinatingly varied. He grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as part of a devout Calvinist family in which activities like going to the movies were strictly prohibited — all biographical details that inform Hardcore and many of his other films to an explicit, significant extent. Along with the Midwest and L.A., Schrader’s name will forever be synonymous with New York City, thanks to his celebrated screenplays for Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver and Bringing Out the Dead; Raging Bull, to a lesser extent), as well as films of his own, including 1992’s Light Sleeper.

His identity as a storyteller, therefore, is spread across a wide selection of environments — just one of numerous traits that continue to make him such a vital cinematic voice. Taking The Canyons as our cue (since attempting to cover everything in a single sitting would likely be futile), this piece aims to track Schrader’s various representations of the City of Angels over multiple decades, starting with the fabulous Hardcore and culminating with the already-controversial new film.

Hardcore (1979)

Though you might be thrown off by the porn industry details and snuff film sordidness, Hardcore is one of Schrader’s most personal works as a writer-director, taking as its subject a direct challenge of the very values he was raised on as a child in Grand Rapids. George C. Scott’s Jake Van Dorn — a scrupulous, successful Michigan businessman (we see his name plastered on both a greenhouse and a manufacturing plant) — is surely a stand-in for Schrader’s own father; in the film, he raises his daughter (Ilah Davis) alone in a strict Calvinist household. Hardcore‘s opening minutes are all gospel hymns and reverent looks at a Grand Rapids family celebrating Christmas, smiles later filling the screen as Jake and his brother-in-law send their daughters off on a California-bound church group retreat.

But a distressed phone call, in which Jake is informed that his daughter has gone missing, sends the typically poised man into a spiral of sex, sin, and lies. He heads to Los Angeles and hires a seedy private investigator (Peter Boyle), who quickly turns up footage of Jake’s daughter acting in an 8mm porno; one of the film’s most lasting images has Scott screaming in rage as the projected sight of his precious daughter being violated reflects off his hardened face. This anger leads Jake further into the pit of Los Angeles, thereby solidifying Hardcore as a film of extremes: on the one hand, we have snowy Grand Rapids, with its family values and church-going habits; and, on the other, we have California, with its nude magazines, flashing lights, loud music, and naked-body wallpaper.

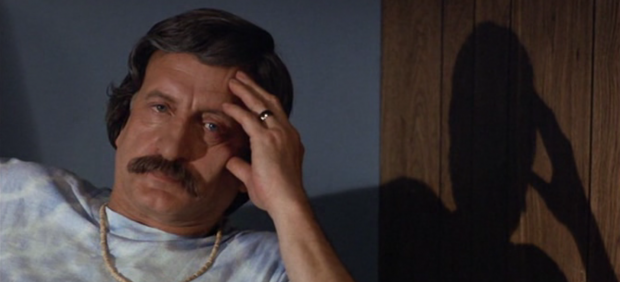

This radical transition is reflected in Scott’s appearance, too: it isn’t long before he trades in the crisp, workmanlike suits for colorful, open-collar dress shirts and a porn-appropriate moustache. (An intense brawl leaves him scarred under the eye, and he thus often wears chic sunglasses to cover up the wound.) Stylistically, Schrader embraces the gaudiness of Los Angeles: Jack Nitzsche’s score becomes increasingly pounding as the movie reaches its wall-smashing climax, and Michael Chapman’s cinematography registers intense blues, greens, purples, and reds on a regular basis. For all this early-career formal ingenuity, however, Schrader never fails to turn the emotional microscope on himself: in the scenes between Scott and Season Hubley’s Niki, you can practically feel the helmer reckoning with his own personal history.

American Gigolo (1980)

Perhaps the closest thing we have here to a clear ancestor of The Canyons, this stylish Richard Gere-starrer anticipates some of the sensations Schrader would bring to Bret Easton Ellis’s screenplay: a removed point-of-view that discourages simple emotional identification in favor of a colder, more ambiguous attitude; carefully sculpted bodies whose forays into intercourse are as professional as they are personal; and a treatment of potentially erotic material that is more discerning and precisely judged than people might otherwise anticipate. It’s telling that American Gigolo would perhaps be remembered more for Giorgio Armani than Gere’s naked body — more often than not, the man is wearing his clothes.

As our Canyons review points out, though, certain aspects of American Gigolo — hearing Blondie on the opening credits, as well as the electronic pulses that occur throughout — exist firmly within the mold of the 1980s. Even though it, too, takes place in Los Angeles, the movie can also be seen as a departure from the world of Hardcore. Whereas the earlier title featured a middle-class man diving into a sleazy red-light district, American Gigolo is a distinctly upper-class study, its high-priced vantage point illustrated in the film’s convertibles, limousines, marble floors, and beach houses. And, save for a late dance-club sequence that contains strobe-lit tracking shots and dominating swaths of red and blue, the movie doesn’t much look like Hardcore, either; it’s more steely and muted, rigid architecture included, and cinematographer John Bailey occasionally incorporates noir-like shadow schemes into his compositions. (Hardcore’s genre genes hew closer to the Western.)

Narratively, the movie appears rather simple, first acquainting us with Julian’s (Gere) regular routines as a pricy escort (he’s a meticulous dresser, and a fastidious learner of languages), and then documenting his unwitting involvement in a murder investigation for which he’s being framed. Scenes of Julian’s budding affair with Michelle (Lauren Hutton), an unhappy politician’s wife, are leveled with interactions between Julian and Detective Sunday (Hector Elizondo), who, because of the evidence at hand, suspects Julian of the homicide. But Schrader and Gere — the latter of whom plays this character as a floating enigma, drifting between scenes as if in a daydream — almost go out of their way to call Julian’s innocence into question, thereby creating a kind of hazy uncertainty. Julian has to give specific performances depending on who he’s with, and this concept of fluctuating identities is something Schrader would return to in The Canyons.

Auto Focus (2002)

Auto Focus is the most conventional-looking entry in Schrader’s Los Angeles canon, perhaps a result of its period piece design qualities. Tor the most part, the movie — which begins in the city, circa 1964 — tends to defer its stylistic requirements to the realms of costuming and production design, with both departments leaning heavily on thick, bold blotches of color. The movie, based on a book by Robert Graysmith (who was portrayed by Jake Gyllenhaal in David Fincher’s Zodiac), also happens to be a true story, and the character beats of Michael Gerbosi’s screenplay emerge in a fashion that’s typical of the biopic genre. But there’s a friction between the sanitary imagery and the lewd material that makes the movie compelling.

The subject of Auto Focus is Bob Crane (Greg Kinnear), a struggling radio personality who found fame as the star of Hogan’s Heroes, a CBS sitcom set during World War II in a German POW camp. A number of the film’s early sequences are warm in a movie-friendly way that generally isn’t the case with Schrader’s Los Angeles: glimpses of the Hogan’s Heroes set, combined with a voice-over from Kinnear that explains the show’s weekly production schedule, carry an almost inherently entertaining behind-the-scenes appeal. A similar inside-baseball charm informs the first scenes involving Willem Dafoe’s John Carpenter, a camera junkie with an uncanny knowledge of “VTRs” (video tape recorders).

From there, however, Auto Focus descends into a decidedly depraved register, as Carpenter’s sex fiend instincts work their way into Crane’s head, transforming the clean-shaven Kinnear (whose all-American looks are brilliantly exploited by Schrader) into something of a world-class sex addict. Schrader details the duo’s nighttime haunts — which they record, often without telling the women, and then later edit / watch — with startling commitment, indulging in the obsessions of his main character without eroticizing them. This pays off in the fallen-star final act, during which Schrader finally allows his style to decline according to Crane’s downfall: the handheld camerawork becomes increasingly rough-hewn, and the bright colors of the opening hour are replaced with bleached, shrill lighting.

The Canyons (2013)

One of the most surprising things about The Canyons is that it’s a movie concerning the death of cinema, or at least the death of the traditional theatrical experience. After reading for months about the on-set disasters orchestrated by Lindsay Lohan (acting opposite adult film superstar James Deen), I was rather shocked to be confronted with opening credits that depict nothing more than a series of abandoned, deteriorating multiplexes. This is clearly a gambit that originated with Schrader (rather than screenwriter Bret Easton Ellis), and this tennis-match relationship between director and screenwriter comes to define The Canyons: while Ellis appears content to examine the surface exploits of his characters, Schrader is attempting to make a film about the “post-theatrical era.”

Comparing The Canyons to Schrader’s previous Los Angeles-set titles is no simple task, since it exists so resoundingly within a 2013 worldview (an admirable, revealing achievement for a director who’s almost 70). While the film’s conversation-heavy opening scene offers its share of empty, Internet-age dialogue, the main source of activity is the characters’ reflexive, robotic smartphone-surfing. The emotional distance this creates recurs throughout the film, as the attentions of characters are always divided across several planes (talking, texting, calling, spying). A sly feat of the film is that it uses this focus on technology to attain an ensemble-like nature, despite the fact that most of the scenes simply consist of two people, alone, talking in a room.

The movie wears its $250,000 budget on its sleeve, crafting a digital sheen that is comatose and, maybe, even dead in its overwhelming greyness. But it proves unsettlingly gripping: cinematographer John DeFazio realizes Schrader’s vision of a departed city with painstaking cleanliness. Aside from the shredded movie houses and a handful of standard exteriors, The Canyons is predominantly set inside the homes of its characters, and the compositions draw on every inch of the exacting architecture to keep the movie visually dynamic. (The scenes between Lohan and Deen feel like they take place inside one of the houses from The Bling Ring.) If Schrader never quite seems to be authentically invested in Ellis’s stale narrative, his personality is felt in the film’s essential iciness, as if that expedition into the world of Kickstarter was less an embrace of the current culture of filmmaking and more a resigned sense of disillusionment regarding the city in which he started honing his craft nearly a half-century ago.

The Canyons will be released in select theaters and on VOD on August 2nd.