Instead of filming a biopic of overlooked fossil hunter Mary Anning’s life, director Francis Lee adapted the little of what’s documented about Anning with a sweeping lesbian love story of his own creation, Ammonite, starring Kate Winslet as Anning and Saoirse Ronan as Charlotte Murchison.

Anning was a working-class woman born into poverty, so despite her achievements as the unsung but leading paleontologist of her generation, very little was written about her because she was poor and because she’s a woman. Lee decided to honor Anning by writing her a fictional love story with a woman, because in her world, men undervalued and overlooked her.

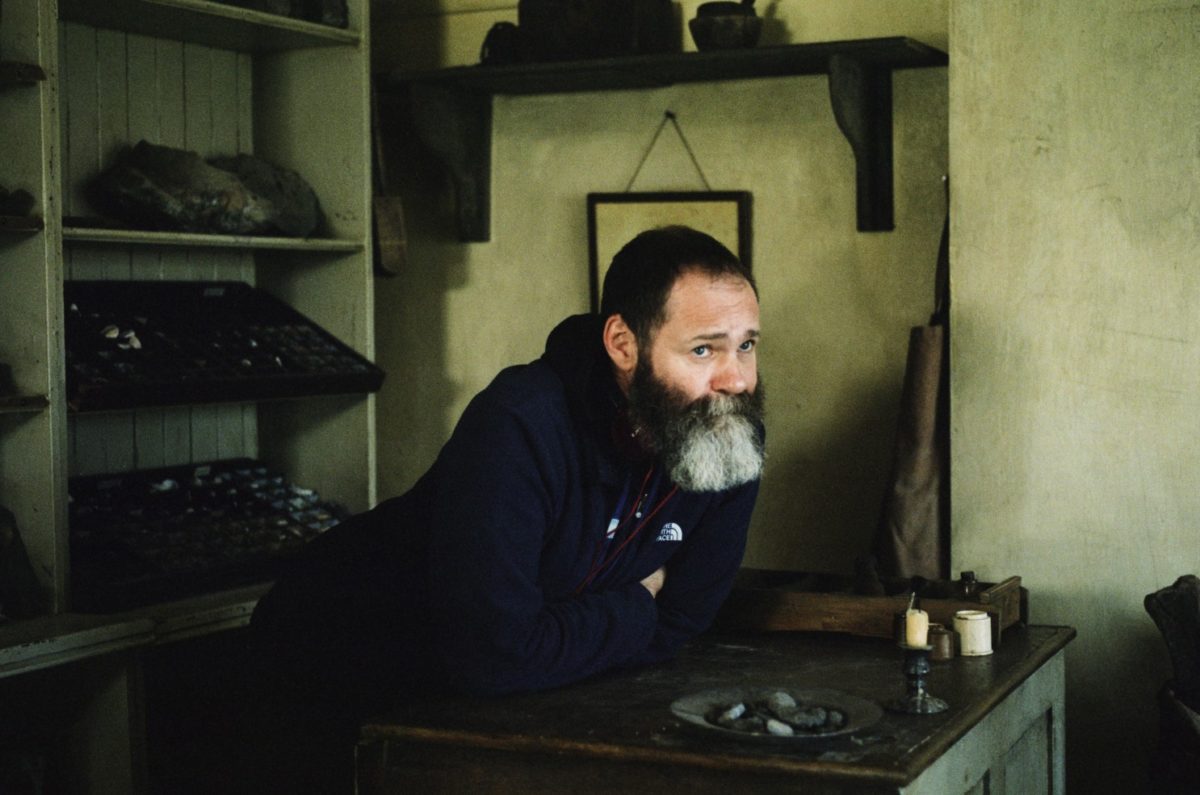

I spoke with Francis Lee about blending biographical and fictional elements in his story, learning how to develop characters from Mike Leigh, his viewpoint of Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, and as Lee calls it, his “obsession” with class and gender.

The Film Stage: You spent a lot of time acting before you got into directing. Did you learn anything from directors like Mike Leigh, who you worked with on Topsy Turvy?

Francis Lee: I was not a good actor. I was quite a bad actor. And I’m very happy to say I gave up acting about 15 years ago. Or it gave me up, I don’t know which. I went into acting, because when I was a kid growing up in Yorkshire, in the middle of nowhere, I didn’t have a great education. A very working class background. I knew I always wanted to write and direct but I just didn’t know how you did that. And I didn’t see anybody like me writing or directing. The only other option I felt was available for me at that time, because I liked telling stories, was going into acting because I could see the route to that. I could see that you could go to drama school, you could graduate, you could get an agent, and hopefully you’d get some work.

So I secretly held on to that desire to write and direct, but I was never confident enough to put my hand up and say, “I would really like to do this.” I was very lucky. As I say, I wasn’t good. I was very lucky. So I did work with some amazing directors, and Mike Leigh being one of them. Mike taught me so much about character, and about how you develop character, and the details of character and the environment. I did take that forward with me when I eventually got to being about 40 and thought, you know, if I’m never going to write and direct and I’m gonna have to get on with it. That’s when I first thought about writing a short film. Obviously, I couldn’t afford film school or any kind of film education. So I learned about filmmaking really from watching films.

There’s so little documented about Mary Anning. You get to reintroduce her to the world and you get to create her character based on what we know, but also what you can imagine. So why did you choose to explore her story through the context of this imagined relationship with Charlotte Murchison?

When I first came across Mary Anning back in 2017, and realized there was but there was virtually nothing written about her by contemporaries at the time, I was instantly drawn to her mainly because of those circumstances that resonated very personally with me. She was a working class woman, born into a life of poverty, in a very patriarchal class-ridden society. She had very little education. And yet somehow, through her own determination, and own sense of discovering these fossils, rose to what we would now call the leading paleontologist of her generation. That journey really resonated with me. I figured that there was so little written about her by contemporaries because she was a woman, and she was a working class woman, and here she is in this patriarchal class ridden society. I knew I wanted to elevate her. And I wanted to give her a story that felt worthy of her. I knew I didn’t want to make a biopic, but I wanted to make an imagined snapshot of what her life could have been.

Also, I’m very obsessed with intimate human relationships, and the machinations around that. So I knew I wanted to tell a story around a deep, intimate relationship. So when I started to look for who I thought Mary might have a relationship with, it didn’t feel like it should be with a man. Because in her experience, and in her life, men had overlooked her. They had, in a sense, reappropriated these incredible fossils she found. So it didn’t feel like it would be an equal relationship. But a woman felt like it would be an equal relationship. And at the same time, I was reading about same-sex female relationships in the 18th and 19th century, particularly an academic paper written by Carol Smith Rosenberg, which documented female relationships through letters that they were writing to each other. And here, what was the evidence of these passionate, emotional, loving relationships between women that had gone unnoticed, as it were. I wanted to highlight all of those things, but mainly to give Mary Anning a very respectful, elevating relationship.

I’m rather touched by the story of making your first film at 40. That you had to scrape everything together to make it all work, through blood, sweat and tears, no less.

A lot of tears, Josh.

Do you think that shapes the stories you tell and how you make them?

I think you’re probably right. Both of the films I’ve made are about characters we don’t generally see on screen: working class people, queer lives, and people who often live at the fringes of society, cut off. Films about loneliness, and those are all the things I experienced when I was trying to make a film. I gave up acting, got a job in what you would call a junkyard. I worked seven days a week, to try and scrape together enough money to try and make short films, because I couldn’t get any funding. I wrote my first film before I started my shift at the junkyard at 9 AM. So I’d get up at 4 AM and write for a few hours every day, not knowing then how you made a film. And also, it made me very determined, rightly or wrongly, but very determined to tell films in the way in which I want to tell them, and to have my process and the way in which I see it, because I fought so hard and sacrificed so much to get to that point. I just thought, if I’m gonna put these stories out there, I want to make sure that when I’m finished with them, I can stand next to them and go, yeah, that’s the film I wanted to make. Because otherwise the sacrifices I made, which were huge, and in the middle of my life––well, hopefully in the middle of my life––would’ve counted for very little.

A few weeks ago, there was an interview circulating with Kate Winslet saying that she moved the sex scene with Saoirse Ronan to Saoirse’s birthday. Will you elaborate?

[Laughs.] I have to tell you, Josh, and I haven’t read any press, but that’s a lovely anecdote.

I can’t remember to be honest. I can’t remember. I remember it was Saoirse’s birthday and I remember we shot one of the intimate scenes on that birthday, but I don’t remember the conversation leading up to it.

Clearly, Ammonite and Portrait of a Lady on Fire are incredibly different movies. But marketing being what it is, the most similar things about movies are what’s highlighted to the public. Did you see Portrait? And what did you think of it?

Okay, so I was totally unaware of Portrait of a Lady on Fire, until it was announced it was going to play at Cannes. At which point, I was halfway through the edit on Ammonite. I love Céline Sciamma’s work, Tomboy, Water Lilies, Girlhood are some of my favorite films, so I was really excited to see it. But it didn’t come out in the UK until March this year. I’m afraid I’m quite old fashioned and a bit of a purist. So I like to see my cinema in cinemas, and it came out and just as I was about to go and see it, the UK went into lockdown, and all cinemas closed. So unfortunately, I still haven’t seen it. Cinema is my happy place. I save all those movies up to go and watch in a cinema in that kind of experience. Maybe that will have to change, Josh, if cinemas don’t reopen?

Will you talk about what you call “your obsession with class and gender”?

I was born into a working class family in the north of England, in Yorkshire. It’s something that has played out throughout my entire life, whether that is access to good education, or financial stability, or social interactions. There’s been so much that I personally have struggled with and fought against because of who I am and where I come from. Therefore, it’s something that I constantly think about, even now, I constantly think about when I’m looking at work, and when I’m looking at characters. Even now, before COVID, when I had to go to a social event, or an award ceremony or a dinner or drinks thing, I get very nervous because I still worry about what I’m meant to do in a social situation. You know, what happens if I pick up a wrong glass or I say something inappropriate, or I drink too much? There are things that still impact on me. I couldn’t go to film school. I couldn’t go to networking sessions because I was working to make money to pay my rent. The idea that I’m a queer man, I understand and see how you can be looked over, and how you can be pigeonholed or put down because of who you are. So yeah, all of those things inform the work I’ve made, and I think will continue to inform the work I continue to make.

Choice is at the heart of the film; choosing how we live, where we live, who we live with, and also the inability to do that. Will you talk about exploring this idea of choice in the film?

This film is very personal to me so it comes from a personal perspective of not always having a choice. Not being able to make those decisions because of your desire or because of what you want or where you want to be. I think those are hard things for people.

What are you working on next?

I’m writing two things. My favorite genre is horror. I’ve always wanted the opportunity to make a really, really fucking scary horror film. So I’m working on that. And I’m working on another personal project. I guess that’s all I can say at the moment.

Ammonite is now available digitally and in limited theatrical release.