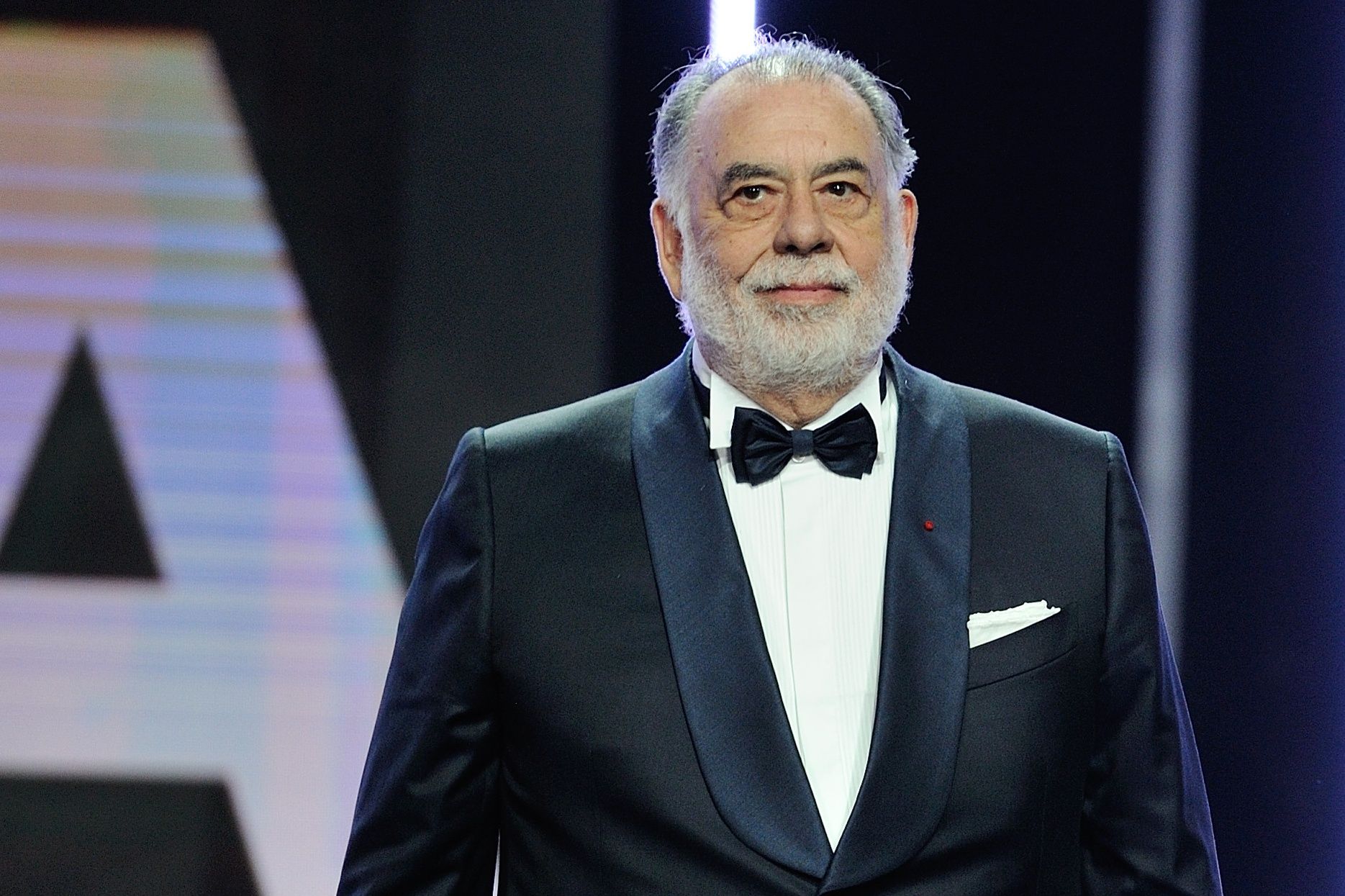

One of the biggest names attending this year’s Marrakech International Film Festival is also one of the most recognized filmmakers in the world: Francis Ford Coppola. Having directed some of the most influential, acclaimed films in American cinema — including The Godfather, Apocalypse Now and The Conversation, to name only a few — his name is synonymous with a kind of filmmaking simply not seen today.

This year he is the head of the international jury, judging the films in competition, and we got the chance to speak with him about a wide variety of topics — cinema-related and otherwise. The man’s encyclopedic knowledge of film history, compounded by his theories on the evolution of the medium, make him a true force. During the roundtable interview, the luminous director generously discussed world politics, violence in film, working with Marlon Brando, what it was like creating some of cinema’s greatest masterpieces, as well as what direction he sees the form moving towards.

There’s footage of you at a press conference for Apocalypse Now with all of your children, and you make the statement that world cinema will be electronic. “It will be digital, it will bounce off satellites, and it will create the screams and hallucinations of the world.” Is there any cinema in the future from this point on?

Definitely. Cinema is in its infancy. The thing that makes it difficult, I think, is that we imagine the cinema as it is now and how we’ve been comfortable with it for the last fifty years. The truth of the matter is it will, like everything else, it will evolve and change, like the theater. We say the theater is thousands of years old. And the novel is maybe 400 years old. The cinema of the future, it would be fun to talk about it, and I do have thoughts and I do think about it, but very definitely, the golden age has not yet come, of the cinema, really. Certainly in the hundred some years it’s been such an abundance of greatness when you think of it. Really, in such a short time to have produced the work. I’ve often thought that the cinema was an art form that was waiting to happen, and of course needed technology to make it possible, and great artists like Goethe – he was a scientist, he was a dramatist, he was a poet, he would have been a natural, but it didn’t exist yet technically. So when it did happen, there was this rush of creativity that produced arguably 12 or more masterpieces in the silent age and then so many more in the subsequent years.

When people say, “What’s the greatest movie ever made?,” I say, “Well where do you want to start? Do you have the time to talk about it?” So it is a rich, rich literature that has already been produced. I always feel like it’s already beginning. That requires that we loosen our idea of what a film—we’ll call it a “film,” still, because it has that name, even though it’s not film anymore – but we have such a specific idea of what it has to be that we perhaps don’t allow what it can be or what it will be. I always like to imagine you sitting here, not even films you’ll make, but your great-great-grandchildren will make. How marvelous it would be if we could even get an inkling. But, no, I feel there’s a wonderful cinema in the future.

Also, you brought the kids with you to that press conference, and I wonder what you’ve done to raise filmmakers? What do children need to become a filmmaker?

I love children. I always have, but when I was 16 or 17, I was a drama counselor in a summer camp, and I would do plays with little children. I would do a play every week. With the 6-year-olds, I’d do a play; with the 7-year-olds, I’d do a play; and then all the way up. And then, with the teenagers, then I would do a musical with the boys and the girls from the girls’ camp. So, you know, I’ve always… when I had my own kids, it was such a treat for me, so I had a rule with my wife, that if I was ever going to go away on a job, I would take them out of school and take them with me.

Most of the time, like if we went to the Philippines, we thought we were going three or four months, but we ended up there for a year-and-a-half. So these were long stays. And I’m sure I messed up their academic abilities to some extent. But being in these exotic countries, we put Sofia in the Chinese school in the Philippines, so they learned other things. And the crews, and the people working on them, as they were often the same picture, became like their uncles and their aunts. They would come to the set and the costume department would make little costumes for Sofia’s dolls, and they’d play in the makeup department. We were like a circus family. Of course, as you know, that’s how circus arts are passed down from family generation to generation.

There’s so much legend surrounding the shooting in the Philippines and Apocalypse Now. And now, looking back, it’s part of the folklore of cinema. Looking back now, what was it like with Martin Sheen and that craziness, and Brando coming, and having him doing what he wanted to do?

You know, there’s a lot of misunderstanding, certainly about Marlon Brando. I think in the way that it’s gotten down, I think it hurt his feelings, the way I talked about him arriving overweight, and he was a very sweet man. He was a very affectionate man, and a genius. I don’t mean as an actor, but the way he saw life, and what he was interested in, and what he would talk about, it was pretty wonderful to be able to just listen. Although he did arrive overweight… you know, no fat person is comfortable with being fat. I, of course, had very practical problems, like what kind of costume should I put on him. He was supposed to be a Green Beret colonel. They don’t make those kinds of uniforms in his size. So I was in a pickle. But he was very forthcoming in his wisdom about life, and indeed, we sat… we had a three-week deal with him, and I just listened to him talk about termites and life and issues. And then I would write up stuff at night and bring it back to him and try to work it in. A lot of the dialogue as Kurtz at the end was his. But really, sometimes out of context, he was talking about other stuff, and I would always try to get it back that it could be you.

Our main experience was as someone who adapted. I was a screenwriter who was good at adapting novels or literature, so I was good at adapting Marlon Brando to be that role. But he had a terrible memory, which is why his acting style was very much “mmmmm.” He was trying to remember the lines! [Laughs] So we did a deal where he would record these little monologues, these little passages that I wrote based on stuff he had talked about, and he would press the button and listen to the lines and do it. But he was a great guy, no question about it. He was an affectionate man — he loved animals, he loved children. So basically I was very scared, because I was on the hook in two ways. I was not only on the hook of this imminent creative fiasco, but at the same time, I was basically the recipient of the debt. In those days, interest was 29%, so I was facing obliteration. I was always willing to accept the responsibility in order to make the film in the way that I wanted to make it, but that was just bluff. There were times in Apocalypse where I was pretty scared. That’s the only word I could use to describe how I felt.

Is there any bad side about having several of your films live as some of the greatest ever?

Well, I have to go back to those days. It’s true that I made The Godfather, The Conversation, The Godfather Part II, and Apocalypse Now pretty much in a row, in a run of, I don’t know, five years. And The Godfather was this tremendous success, even though it was critically a little batted back and forth at first. But the other films weren’t immediate – thought of well. And I, like all filmmakers, was prone to getting really depressed about the reception of my films. Like people ask me, “Do you care?” Well, yeah, of course. I like to cook, and if I make a dinner for all of you, and then you go out and say, “That was a terrible dinner,” that makes me feel horrible. So I was very despondent during those years. It was only over time that some of them… like, Apocalypse Now was very dicey when it came out. It was not… people were interested in it, and people went to see it, but it was slow, over years, it was more accepted as something more worthwhile. So I didn’t know that these films might be thought of as classics.

Consequently, films that I made even more recently, you see there’s a process where the public or the evaluation changes over time. So now, as an elderly person, I look back and think, “Isn’t that strange? I was so suicidal over that or I was so miserable.” It makes you realize, if you’re younger: just do it. You never know what’s going to happen. It is odd to me that some of those films are thought of so well. I think what I did have was that I wasn’t afraid. When you make a film, sometimes you rub people the wrong way, because it’s different from what people – like painters in the Belle Epoch, they were doing these pictures and they couldn’t sell them on the street corner, and yet the paintings that were sold by the Academy, we don’t even know their names, but Manet and Monet and all those guys, they couldn’t get arrested. I think always it changes very quickly. I like to say the avant-garde art becomes the wallpaper. It just changes. And that’s happened with film now. Even with films we see now, more hold back what they’re saying and make you work to understand. That seems to be more of a common… and I agree, if you use the audience to fill in the spaces, I agree, it’s more wonderful for the audience, but when we were seeing Antonioni films, like L’Avventura, what happened? What was it about? It was so different. But as time goes on, things change.

What do you think is cinema’s role in bringing some order to the chaos in the world as it relates to terrorism? And secondly: we saw Bill Murray saddened by Paris and San Bernardino over these massive gun massacres, and shift to introducing his film about automatic gunfire. Do you think it’s an overreach for people to consider some of Hollywood to be critical of these things when there’s so much violence in the films?

I absolutely don’t think it’s overreaching. It’s obvious that films that have action — and action nine times out of ten means violence — are common and fill up the commercial pictures. I know the producers say that’s what the public wants. But I don’t agree with that. Did you ever see a movie called The Burmese Harp? It’s a beautiful, beautiful film after the war. But a real pacifist film is filled with love and doesn’t have any violence in it. I would go further: it’s not only that movies and the automatic gunfire and film after film, but it’s also the press. I really wonder what would happen, say about ISIS, if CNN and CNBC and Fox would all agree that they shut up about it and maybe just on Sunday at 6:00 have a report of it. That everyone knows that television that the Islamic jihadists get is what is holding them up.

I have no doubt that if we’re not going to watch it, take it off the air, that their recruitment and their funding and their energy would just disappear. It’s so easy to do. Because I was wondering during the last ridiculous Afghanistan War, I would notice CNN would show the jet bombers taking off, and I knew it took 11 minutes. I was like, doesn’t the enemy know it’s coming? What happened to surprise in military? It’s so funny what’s happening in our country that is making this possible. Not to mention the roots of it, which probably go back to WWI, the resolution of things when England gave the same piece of property to the French that they did the Jew, the Belfort Agreement, and to… before Saudi Arabia, when it was King Hussein. It isn’t hard to understand the struggles. They go back a long way.

Who was it who said it? It was either Descartes or Voltaire said, who believe in “absurdities commit atrocities.” They have these fundamentalists taking the wrong parts of these religions, and I don’t even know where to find what they’re taking. I did a little study on my own. It seems to me – I am very hopeful for the future, but from the point of view – people say terrorism, what is terrorism? Terrorism is when you don’t have an army and you use anything else you have. We were terrorists, the United States. The Jews before Israel were terrorists. Terrorism is a word that’s used on these people, and that’s horrific, as some of these news sects are. Sometimes what’s called terrorism is a last resort for those of who don’t have jet planes so they use what they have. That being said, I’m as heartbroken as myself, we should be busy in our world building this Utopia. We’re still dealing with these ancient issues. I’m by no means a political expert, but I know a lot about the Middle East, I know a lot about Islam, and it seems to me we’re not confronting the threat as effectively as we might.

So the answer of what cinema can do, getting back to your question, is education. Most people don’t know anything about the so-called enemy, they don’t know anything about Islam, they don’t realize that it was the height of civilization in the 13th century, or that the Quran and Islam is full of – when I said when I first spoke – the first page of the Quran is about God as righteous and merciful, and it stresses it over and over, it repeats that. And it says, “Go the way of that he has been blessed.” Which must mean righteousness and mercy, and not those who are misguided. So I feel education and learning about these things, which are being portrayed as evil, would be helpful. If we know more, if everyone knew more about what was going on, about what the issues really are. Perhaps that would be of help. Perhaps someone could do that instead of having gun fights.

Do you feel now in your career you want to focus on these issues? You were saying earlier how Hollywood is too violent, but a lot of your early films have violence in them.

That’s why they were successful! I was just a hireling. The Godfather was a book and they hired this 27-year-old guy because he was Italian-American and he would take the heat, and Italians were insulted by it.

But you said you were researching things like terrorism. Is this a kind of subject that interests you?

When I say researching, I mean I wanted to learn. I’m fascinated with the Middle East, and how it came about that so much rankling and anger. It’s not hard to understand why people would be upset by certain things.

You talk about a future in cinema that’s handed down through generations. Does that involve the type of things that interest you?

What you say makes me wonder, because I was looking at the New York Times and all the movies, and it occurred to me that they all look like sausages. Here’s this movie and then there’s this movie. And it’s like – now that I’m old and it doesn’t matter, I was thinking, I really don’t want to make a sausage. I just want to make a stream about what I’m feeling and what I’m thinking about and what I’m feeling about, and maybe cinema for me will be one long project, and maybe I’ll make only one more film while I’m alive, and it will go on and on, and it will change and go into this and onto that.

Do you think that this project is also possible for a younger generation of filmmakers? Because you said you’re old and you can always do what you want.

I’m very sad in that I think it’s harder for a young person to make a more personal film today than it was when I and colleagues of my age were struggling. And if you do get to make it, because you get the money somehow, then it’s hard to get it released, to get distribution. I am certainly admiring the young filmmakers, not only for the beautiful work that they’re doing, but with so much against them, to try to get it released; it’s so difficult. You know, I read a lot now, and I have a rule never to read anything related to a possible movie — not that I even have a possible movie.

‘So my reading is this strange: I was reading about the assassination of the Israeli Prime Minister, and now I’m reading George Orwell’s Burmese Knights, and I was reading Donkey Heart just recently. So my reading is just kind of rows or rivers, maybe it would be nice if I could have a film like that, in that sort of way. But I have an idea of the future that I speak of, related to your great-grandchildren. I have a hunch about the directions it could go in, just as 34 years ago I knew for sure that it was going to become digital and have digital effects, and CG and all that stuff. But I have a few hunches about that.

Would you elaborate on one of them?

I’d be happy to. What I believe is that — and it was all sort of hit by the harp – what was the 3D movie that came out? Avatar. It was around, and everyone was saying this is the future of the cinema. It’s 3D. I said, “The cinema, we had 3D in 1952 with Bwana Devil and House of Wax.” 3D with glasses cannot be… the cinema is too interesting and too big for 3D to be anything. And there were announcements, you remember, “All movies are going to be 3D” and executives were saying this. So I started thinking about it and I realized that what we’ll call cinema of the future will change in a couple of areas.

As always there’s writing, and by that I mean the screenplay. What are screenplays? I don’t mean the form of a screenplay, but the act of committing to paper of what you movie will be. Just as the theater or dramatic writing changed over many years. And the novel changed over many years. In terms of areas of point of view, of stream-of-conscious with Joyce and Virginia Woolf. So the very screenplay, how we approach — and we’re starting to see it even with the movies I’ve seen here — how a screenplay is organized and the project put forth in writing is a tremendous opportunity for innovation and evolution as with the novel. So that’s one area.

Then the phenomena of the documentary, and the documentary form that we think of. If you go back originally, it was always, it was never really purely documentary. They did retakes and staged things; you have to. But that form has such a wonderful effect when it’s used to tell a fictional situation. I speak of Sarah Polley’s film called Stories We Tell, where this thing comes around and it becomes so personal. That, to me, seems like a very exciting feature, the reconciliation of the documentary form with the classical fiction form. And then there’s the fact that cinema is now digital, meaning the projectors are digital. They’re pretty impressive when you think of what they are now compared to what they have been, and the fact that they don’t take cans of film means that they aren’t edited, they don’t have to be edited. They’re digital files, and, if they’re digital files, that means they can be different every night, or they could be performed live.

So that takes me to another branch which I would call live cinema, for lack of a better word. Which is very different from live TV. Recently what I’m speaking of is that I’ve had a piece writing for some time, and I took 30 pages and I went to school in Oklahoma, and they gave me 70 students, because I had a big stage, and I did 20 minutes just to sort of feed what I was talking about. A lot of times in my career, I’ve done a lot of things without really knowing, as you might have guessed. When I went off to do Apocalypse and I had to do that helicopter scene, I was like, “What was I thinking? How do I do this? I have no idea how to do this. I have to have all these helicopters blow up a village and stuff.” So I sort of learned by doing, as we often do. So when I went to Oklahoma and I started to do what I thought was live cinema, it was sort of the same thing.

It was so interesting when, in an attempt to do it, I learned about it. I learned so much in the little 30 pages, in what turned out to be a transmission of 54 minutes. And as I was working on it, I kept thinking, “This is not theater, this is not movies, and this is not television. It’s something different.” Because live television really always… and, in its greatest time, it’s about coverage of an event, be it a sports event or a play. What’d they do, Peter Pan recently? Cinema, just as in writing, the basic unit is the sentence. In cinema, it is the shot. Live cinema is, if you can imagine, like if you saw a storyboard from a Pixar film and the actors were poking around the storyboard doing it as a film with shots and cars and everything we are used to, but in the end it was a performance.

That’s sort of what we did, and it was so exhilarating when I realized that this was possible, because the technology that’s been invented for sports has only been used for sports: football games, soccer games. You could use it for storytelling, and it does some very magical things. So all in all, I’m extremely enthusiastic about these. Not that the whole cinema has to be. You gain a lot by having the control of having takes and being able to edit. But there’s also something that’s always wonderful about performance. Like when they did those operas in the 18th century, they were like huge productions, but they did it for them live. I saw Aida the first night. That you could have in film, too. All in all, I just want to have… the horizon is very wonderfully big, and there are many possibilities. Only our own prejudices of what a film shouldn’t be will hold us back.

You said that you know a lot about the Middle East and Islam. From where does that knowledge come? I hope not CNN.

Oh, you wouldn’t get it from CNN. The only place knowledge can come from is reading. For example, I don’t know if anyone… we talk about Syria, because Syria is such a beautiful country, as we’ve had the pleasure of seeing it before this destruction. And after WWI, you remember Lawrence of Arabia? Alec Guinness’s part? That was Faisal II. Faisal II was the son of Hussein, who was before Saud — which would become Saudi Arabia. He was of the Hashemite Kingdom, and Faisal II went into Syria through their own military with Lawrence, who was like a spy, and became the king of Syria. I read his biography, and he was such a great man, and the first thing he did was try to understand all the groups. There’s the Druze, there’s the Alawites — so many people, that he started to really be a king.

And he was very generous. They would come and discuss and stuff. And then the British had given, with the Sykes-Picot Agreement, or Peko, had given it to France, and France sent the military and evicted Faisal. So Syria had a government, in a way. It was a monarchy, but he was a very enlightened man. Great man, from the book I read. So the British felt bad about it and made him the king of Iraq, and he started to do the same thing in Iraq. So whenever there was the opportunity of a real government that was appropriate to a land that had been dominated by the Turks for 400 years… so, no, my knowledge is from reading. CNN, you wouldn’t learn anything. I wish CNN would just shut up about the Middle East and breaking news. That’s not at all breaking news.

Val Kilmer recently made a joke tweet about Top Gun 2. Did you read that? He joked that you were going to direct it.

Yeah, but the Internet is like that. They say so many things that are not true, but you kind of chuckle. It’s not of any importance.

I wanted to go back to cinema for a little bit and ask if there’s literature or other forms of visual art that inspire you, where you look at it and you see possibilities to take to cinema.

Well, it’s true, reading a lot of fiction, and non-fiction as well, I’m always struck with how more interesting they can be in that format. I go see a movie, even a good movie, and how it’s got to do it all in two hours, and how it has to make the part melodramatic in order to satisfy the audience. I wonder when cinema can really grow up to be the literature of our people, of our time, because it’s not. It could be literature, but it’s not even classified as that; it’s entertainment. And certainly the filmmakers have no control over it whatsoever. They’re just trying to get another job, unless there’s the one or two who are… even if there’s the one or two who are, but very few. Even Steven Spielberg, who is arguably certainly at the top of the thing, he has to wheel a deal and cut the budget to make something. And now, with the big Chinese population being moviegoers and having the affluence now, they love action film more than anything, so it’s gonna make it worse for a while.

Today you have two kinds of movies: big, box-office movies and small, independent movies. And Steven Spielberg and George Lucas said there is nothing between those two extremes, and the system is going to explode because of this. Do you agree?

I feel that the changes that you put your finger on… that really isn’t television anymore. It’s all become one cinema, and it can be under a minute or it can be over 100 hours. I believe that the entire business and industry will have new ownership in three or four years that won’t be owned by the people who own it now. It won’t be those businessmen, and it will be owned by a different group who are desperate for content, because they have a lot of money, and of course all the internet companies. I mean, you look at Yahoo floundering, and even companies that are successful — like Facebook and stuff — they’re all based on advertising and always more. Anyone who’s been on Facebook, if you’ve been on it for a few years, you’re thinking, “I’m never going to go back and it’s a waste of my time.” So they’re going to be all in the movie business. And whether that will be better, I don’t know. [Laughs]

Like Sony: when they first became a movie company, the first thing they did was hire all the old Hollywood executives. But I believe there will be a changing of the guard of the owners and the way it’s distributed. And the idea that there’s movies in theaters, separate. Movies will be… the movie that you go to the theater with, which will still be a wonderful option, you’ll be able see at home again that night. The idea that theater owners want to make a window, what they call a window, the public will have what they want. So I think you’ll see a lot of changes. By virtue of new owners, maybe some smart people and this work will be available anywhere. You can see it in your hotel room. You can see it in a movie theater or a church, or a community center. For lack of a better word, media will be available everywhere.