Filmmakers Amp Wong, Ji Zhao (directors), and Damao (screenwriter) have taken the Chinese fable Legend of the White Snake and reformatted it into a prequel/remake with sequel possibilities (if a mid-credits sequence is any indication). The concept of reincarnation keeps the characters the same despite letting them meet five hundred years in the past. That’s how long snake spirit Blanca (Zhang Zhe’s Xiao Bai) has practiced Taoist magic while waiting to achieve Immortal status alongside her sister Verta (Xiaoxi Tang’s Ziao Qing). Rather than be five centuries since her creation, however, this wait begins after a test of her moral fiber upon being tasked by her Master (Wei Liu) to assassinate an evil General (Yaohan Zhang’s Guo Shi) maliciously siphoning the vitality from snakes to augment his dark arts power.

She doesn’t remember this at the opening of White Snake, though. Instead she’s shown forlornly wondering why it has taken so long to ascend to the status she’s strove to honor her entire life. It’s only when Verta gives her sister a hairpin she says was Blanca’s all along that the memories come flooding back via flashback. We’re taken from the serene majesty of these demon spirits in human form wading through water to a fast-paced action scene where Blanca clandestinely moves closer to the General’s headquarters, that hairpin a magically flying weapon taking aim at his back. Before it can stop him from draining her brethren of their souls, however, his right-hand (Boheng Zhang’s Little General) interferes. Blanca then suddenly awakens elsewhere without her memory.

Her new setting is ironically amongst snake catchers—the very same who supply Guo Shi his means for power as taxation. The young man (Tianxiang Yang’s Xu Xuan) who came to her aid isn’t like the others, though. Not only does he dabble in divination (he’s an I Ching pro) and medicine, he’s actually afraid of snakes and thus never captures any during a hunt. So it’s no surprise that he starts to fall in love with Blanca once danger helps manifest her unknown magical powers, the fun they have while returning to the spot where he found her bonding them despite the cultural impossibility of a union between human and demon. It’s a strong enough connection to even endure Xuan’s inevitable discovery that Blanca is a snake.

It can’t matter to him once they realize her identity has put them in the crosshairs of Little General and Blanca’s Master simultaneously. He wants to set an example that nobody gets away with attempting to murder his boss and she can’t be certain her once famed warrior hasn’t defected if rumors of human fraternization are confirmed. Luckily for Blanca, Verta volunteers to lead the hunt—hoping to reclaim her sister alive when any other snake spirit might have just killed her on sight. And as the “White Snake” regains her memory, the war between who she is and what she now wants (Xuan) can’t help but risk tearing her apart on the road to the reckoning that is an impending collision of their two worlds.

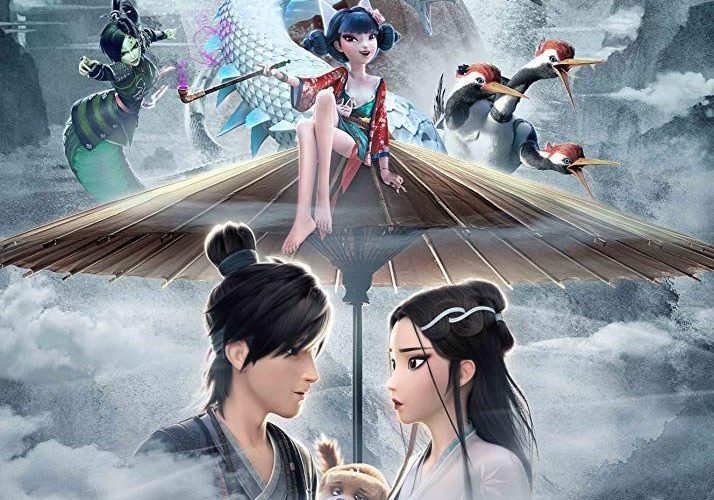

The fable isn’t unique in its forbidden romance tropes, but what fable is? This is an ancient story that’s been made into numerous films, operas, and television shows while also being copied and appropriated by other cultures around the world. Rather than fault its familiarity, you must either accept or reject it. I don’t think the former is difficult to do considering the kinetic action, fantastical surroundings, and often-beautiful animation (I say “often” because there are some moments where characters look like flatly unfinished videogame renders). These women transform into giant snakes twirling through the sky with violent intent as their human magician counterparts throw cards and beams of light back at them to create some stunning sequences unlike anything you’d see in a Pixar film.

That violence juxtaposed with Light Chaser Animation’s more westernized computer-generated aesthetic shouldn’t, however, be ignored by parents hoping to bring young children to the theaters. While it looks more Disney than anime, it’s also not without using sex to depict love (tastefully) or sexualized characters that would fit perfectly in an anime like a fox demon who manufactures weapons with mostly evil intent (Xiaopu Zheng’s Jade). Wong and Zhao effortlessly move from the comic hijinks of Blanca enchanting Xuan’s dog Dudou (He Zhang) with the ability to talk to the two characters’ one-night stand before a big fight. While not a big deal (there’s no nudity involved), America’s prudish nature might still object. So be warned when your kids ask to go if White Snake comes to town.

Its themes of inclusion, greed, and heroism shine brightly otherwise while its fight scenes embrace their stakes to amplify the suspense and allow characters we’ve come to care for teeter on oblivion’s edge. Some plot points are rushed (Blanca’s rebuke of Xuan after their evening of passion is so abrupt that you can’t help thinking you missed a conversation somewhere), but they’re easy to overlook when White Snake’s success truly lies in its visuals. We want to experience Xuan’s transformation to assist his love in her fight and witness the elaborate, magical assault Guo Shi unleashes to ensnare his prey knowing their essence is the equivalent of a thousand regular snakes. Eventually the townspeople must recognize life isn’t black and white. The difference between a Demon and God is small.

White Snake played at the Fantasia International Film Festival and opens on November 15.