Don’t mess with a Nepali “cantara” on New Year’s—especially if you’re a virgin. Had young Nico (Javier Bódalo) only been warned, he might have avoided the worst nightmare of his life. While his virginity wasn’t for a lack of trying (or spilled drinks, vomit, and curt rebukes), somehow surviving a night in the home of the first female to ever look at him with desire (Miriam Martín’s Medea) could force him to never want to undress again let alone wish to do so in the vicinity of a woman who might potentially let him. Let’s just say that Nico’s travels to a cesspool of urban filth (Medea’s bathroom rivals Trainspotting) in hopes of being deflowered by someone twice his age don’t quite turn out how he imagined.

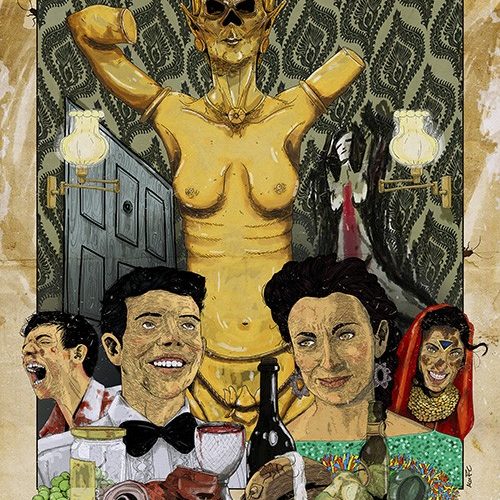

The film that has Nico by the balls (although anus may be more appropriate) is The Night Of The Virgin. Directed by Roberto San Sebastián from a Guillermo Guerrero script, this two-hour horror flick brimming with bodily fluids looks to capture the attention of splat-stick fans that adore genre predecessors such as Peter Jackson’s grotesquely entertaining Dead Alive. And for the final thirty-five or so minutes it reaches those heights of repugnant excess as its disgusting locale is covered in blood, semen, excrement, and amniotic fluid to name just a few forms of discharged “humors” we experience onscreen. Between the human and demonic screams, bodies dragged by umbilical cords, and faces scratched to deformity, its target audience should be pleased.

While I’m not necessarily a member, I do enjoy a splatter-fest done right with ample comedy and no limits. This doesn’t quite fit those criteria, however. Many of its faults lie in its middle hour’s excruciatingly slow pacing despite all the necessary set-up for its unforgettable finale already being successfully explained during the first twenty minutes. We know very well what kind of weirdo Nico is (his psych-up dance contains nipple rubs and two finger salutes after all) and find ourselves prepared for his world to flip upside down at the behest of Medea’s mysterious and deliberate predator. And we comprehend the crash course in Nepali mysticism her Spaniard embraces like a Bible, the ritual to resurrect Naoshi (goddess of the unborn) appealing as a worthwhile gross-out endeavor.

So why does it take so long to witness the fruits of our labor? (Yes, this middle portion is laborious to say the least.) You have to introduce Medea’s homicidal ex-boyfriend (Víctor Amilibia’s Spider) to advance the chaos coming, but it’s enough to respect his rage the first time he incessantly pounds on the door to kill Nico. We don’t need to rehash it again and again. The same goes for the constant back and forth between Nico and Medea: their will they or won’t they have sex for pleasure, revenge, supernatural necessity, or whatever else shtick. It’s like we’re stuck in stasis, the constant repetition of actions lowering the stakes they once possessed until their culmination loses all impact beyond thanking God it might be over soon.

San Sebastián and Guerrero do finally give us something to cringe at (or salivate about depending on your appetite for explosive diarrhea amongst other unsavory releases), but my patience had already worn thin by then. Once you start wondering whether the descriptions of insanity were lies or written by those with too weak a stomach, checking out is unavoidable. I felt trapped within the main locale of at most five rooms, wanting Spider to break the door down and inject some life. But we instead have to listen to the same threats fifteen times while losing the tiniest shred of sympathy we once had for Nico. The boy isn’t endearing and Medea’s evil potential as worthwhile threat wanes as time goes on. Eventually I forgot Naoshi’s presence completely.

The only thing that could have saved this extended set-up is laugher, but the constant use of “granny” jokes on behalf of Nico’s not-quite friends via WhatsApp aren’t my idea of comedy. It’s not funny to hear Spider swear while Medea pretends to bed Nico or to watch Nico lose his desire for sex as Medea starts scratching her face off. He was okay with a chalice of menstrual blood in the bathroom but a few facial cuts are what get his gag reflex going? To me the effective humor arrives with the absurdity pushing way beyond clichéd circumstances. It’s Medea’s choice of hiding place for Nico’s phone that got me laughing. It’s the close-up of a baby’s crowning head trying to escape a butthole that tickled me.

And I think that’s the film’s goal: to delight with an excessive use of graphic content and unbelievable situations. Painting three-quarters of the runtime as “real world” plausible while the supernatural intrigue fades into the background therefore subverts that mission. Only when the rules are thrown out so San Sebastián can bust out the hoses and let fluids fly for Naoshi does interest crest. Unfortunately this transition also serves to prove just how boringly ineffective everything that came before was. I can deal with overlong reaction shots that border on tedium when they’re in response to a grotesque development holding what’s sure to be a wild result. I can’t blindly endure a revolving door of Spider (“Let me in!”), Nico (“Call the police!”), and Medea (“Get out!”) nonsense.

That doesn’t mean The Night of the Virgin won’t find a rabid following. For some the end’s chaos is enough to hail the work a masterpiece of the genre or at least a worthy entry within. To me it’s too little, too late. I wish San Sebastián and Guerrero stuck to the Nepali legend as their main focus rather than introducing its uniquely fascinating motivation before rendering it the farcical cause of a domestic spat dissolving any suspense previously built. Rather than be the backbone to a roller coaster of bodily discharges, it becomes a punch line. So when the literal excrement finally hits the proverbial fan, we can no longer give Naoshi the respect she deserves. Rather than powerful deity, she becomes an excuse for gross-out effects.

The Night of the Virgin screened at the Fantasia International Film Festival.