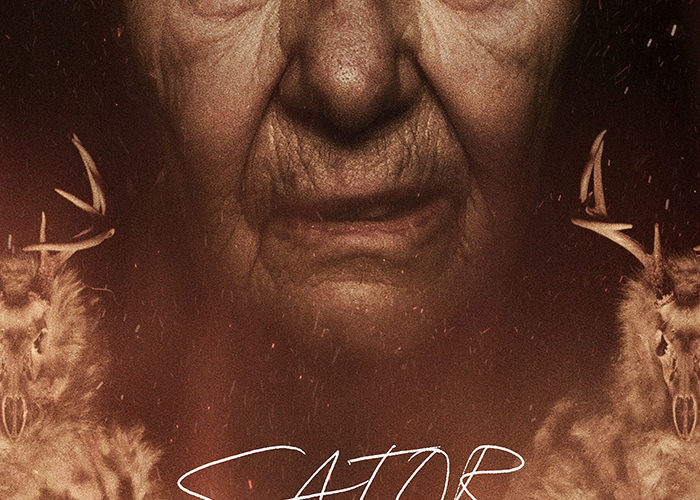

Jordan Graham’s grandmother used to hear voices and write the words being spoken down as though they were messages she needed to both understand and follow. She called the orator Sator, “his” name scrawled upon the pieces of paper that ultimately gave these trances permanence through physical form. I can’t imagine how it must have felt for writer/director Graham (who also takes on pretty much every other behind the scenes position a feature-length film demands) to experience the phenomenon—especially considering June Peterson wasn’t the only one in his family to have her dementia take that form. Her mother was afflicted as well as her mother, the voices becoming a mainstay for generations. And when June finally lost her memories of everyone she loves, Graham admits she never forgot Sator’s name.

It’s a fascinating bit of reality perfectly suited for the supernatural horror treatment wherein this unearthly being is brought to life with malicious intent. So Graham crafts a mythology that says this creature is a demonic presence in need of sacrifices by fire, his voice choosing those with the capability of becoming his disciples while those without are dismissed as potential victims to be gifted as payment for the others’ enlightenment. Or at least that’s what we’re told since the opening prologue of Graham’s film (full frame and black and white) portrays it as truth. Nani (June playing a fictional version of herself) and her daughter (Wendy Taylor’s Mother) stand in rooms filled with candles, the latter setting someone ablaze before rising into the sky above the flames.

The sequence proves eerily foreboding as the camera deliberately moves through the house, revealing secrets and characters more flashbacks, photographs, and home movies will soon introduce. Graham doesn’t tell us how much time has passed once his screen expands out and adds color, but we’re slowly made aware of the changes that this family has underwent. Grandpa (James W. Peterson) has passed on, Mom has disappeared, and Nani has begun to forget her grandchildren. There’s the stoic Adam (Gabriel Nicholson) who serves as the film’s lead, desperate to put the past behind him and live a simple life hunting deer in the woods. The more outgoing if equally severe Pete (Michael Daniel) visits from time to time while Deborah (Aurora Lowe) appears to have stopped coming back completely.

The quiet that surrounds Adam is anything but peaceful, though, as whispers are heard and paranoia mounts. He moves amongst the trees with his dog, blowing a wooden whistle in hopes of attracting prey he’s unsure even exist since the “deer cam” his grandfather set-up refuses to record. It might be that nothing has stopped by to trigger its motion sensor or perhaps the digital memory card is faulty. With Pete’s help he can switch it out, but it’s uncertain if Adam even remembers who his brother is to accept assistance and not just shoot him in the chest. To watch Adam visit Nani is to see him keep his distance—almost afraid to confront her in case Sator threatens to take hold like “he” did his mother.

Graham moves from one day to the next, abruptly shifting night to morning after creepy visuals (a lone flame crackling in the distance), creepy guests (Rachel Johnson’s Evie virtually sleepwalking through life more than Adam), and creepy sound design (he supposedly spent over a year of the film’s five-year gestation perfecting the sound) to fray our nerves and inch ever so closer to a mysterious climax. Adam’s dog snarls at nothing, the “deer cam” takes a darkened image of trees, and an apparition in animal furs and a skull mask enters his home uninvited. Is he spiraling out of control? Or has Sator come to make “his” presence known now that Nani is too old to do his bidding? The dread amplifies as “his” terror takes shape.

The result won’t be for everyone as the pacing starts art-house slow and never picks up speed. Think It Comes at Night with its forested locale, minimal cast, and anxiety-inducing potency taken one step further to blur the line between psychological breakdown (humanity is the monster) and supernatural malevolence (something is pulling their strings). Graham isn’t interested in giving us concrete answers because that air of the unknown that surrounded his real-life grandmother to inspire this nightmare is forever more effective without them. So he intentionally avoids dialogue, a clearly marked passage of time, and the difference between reality and dream to ensure we’re as unbalanced and prone to deception as Adam. Eventually one more fast-forward lets the epilogue deliver an unforgettable exclamation point of brutality.

Graham has carefully composed Adam’s (and our) progression by hinting at details that will only be given focus when the time is right. First, it’s the prologue providing us faces without names. Then there are snippets of conversations that our minds must decipher with what little context we have alongside photographs in Nani’s house and another black and white memory of eyes starring at us from down the hall before a videotaped birthday brings clarity to how that opening sequence could be real without being real. Everything has a purpose, from the deer whistle to a clearing of bleached white skulls, as modern medicine diagnoses that which our minds can safely process while our eyes warn us about how much worse things might be outside the realm of science.

Sator played at the Fantasia International Film Festival.