And here I thought capitalism’s hold on the American education system by way of unpaid internships was bad. As documented in July Jung’s extern drama Next Sohee, what’s happening in South Korea is even worse. It all comes down to incentives—not for the children, but the institutions profiting off their labor. When big companies with huge executive payrolls (since managers need managers who also need managers while hourly employees become statistical cogs in the slave machine) need cheap and naïve workers to fill call center desks or factory floors, they knock on the school board’s door offering positions. Since districts’ budgets are beholden to quantitative competition, schools say “thank you,” blindly assign their students, and threaten that quitting isn’t an option. Such “disgrace” is monetarily unacceptable.

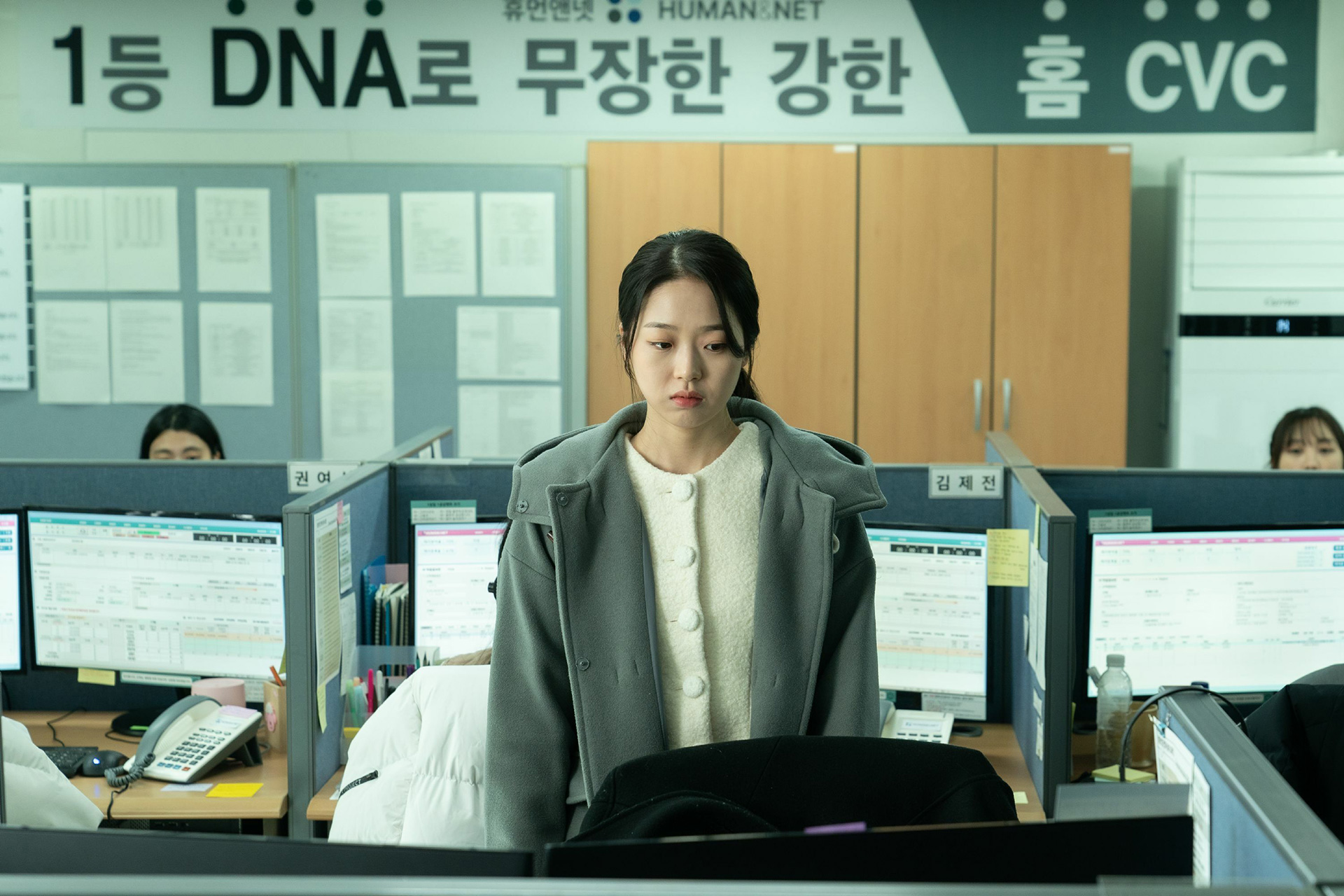

So-hee (Kim Si-Eun) is told she’s won the jackpot. Despite being an animal care major whose passion is dancing, it should be taken as an honor that she’s been offered a position with the subsidiary of a subsidiary of a major Korean corporation. She puts on her best clothes for the interview under the impression that prestige and professionalism is part of the deal. They barely talk to her, though. They barely look at her before saying she starts the next day. What is So-hee supposed to take from the experience as a teen who’s never had to deal with such things? Where it should send red flags that her new employer wants nothing more than warm bodies to sit in their chairs, she remains hopeful.

In the first 70 minutes Jung does a wonderful job portraying just how insidious this dynamic proves. We watch the life and fight that defined So-hee’s identity slowly slip away. One of her first scenes is at a restaurant with her friend Jjoonny (Hoe-rin Jung). The latter has quit school (due to them not allowing her to quit her extern job) and now makes money by streaming online. While eating, another table of men begins loudly talking about her profiting off her looks while they, “talents” who know how to color videos and not simply get by on the technology itself, languish in poverty. So-hee doesn’t think twice before rising to her feet and physically accosting them to prove they’re nothing more than whining babies.

To see that, as well as the joy radiating from her when meeting a fellow dancer friend Tae-jeon (Hyun-oh Kang) outside his work, is to see a young woman going places. So-hee knows what she wants and isn’t afraid to do what’s necessary. Does she aspire to answer phones for a telecoms-Internet company forever, delaying and passing customer grievances onto her co-workers indefinitely to milk as much cash from them as possible before finally processing their cancelations? No. It’s a means to an end. It provides her money to live her life and credits to graduate. If she must be berated and harassed on that path, it’s apparently just the way it is. At least that’s what everyone in authority says, explaining via textbook deflection.

A lot happens in a short period of time until there are two deaths and a host of other depressive episodes brought on by over-work. It leads to the film’s other hour, led by police detective Oh Yoo-jin (Bae Doona). We don’t learn exactly why she had to take time off, but her first case back is what her chief considers a slam-dunk: a cut-and-dry suicide. Yoo-jin agrees too. When she objectively looks at the evidence in front of her, that’s exactly what she sees. There’s a wrinkle, though: she knows the victim. This fact isn’t necessarily enough for her calculating nature to change her perspective on the case alone, but it does cause that objectivity to wane long enough to recognize there was a culprit.

Like so many stories of this nature, however, naming said “culprit” isn’t so easy. Not when it’s revealed to be a system composed of numerous co-conspirators all kicking the responsibility can down the road to someone else. Because who is to blame in these situations? Is it the companies that hire inexperienced laborers (like So-hee) to exploit them? Is it the teachers who let those companies do it because that’s the cost of keeping their jobs? How about the schools who consider the psychological toll of their students the cost of keeping the lights on? How about the Ministry of Education creating the environment for such cutthroat exploitation? The Labor Ministry? The legislature? The president? Or should Yoo-jin follow their lead and blame the deceased? Blame the victim.

Next Sohee handles a heavy subject with a steady hand. Jung showcases the system of gaslighting that’s necessary to manipulate an entire nation’s youth and reveals what the perpetrators really think “strength” means by way of putting the camera in their faces to watch how every single one of them must involuntarily turn away in shame. The tragic truth, too, is that the heroes who can instill real change rarely get to see it in action. Whistleblowers get arrested or have their reputations destroyed. Speaking up to power either earns more incentive to stay quiet or the type of emotional and existential crises that lead to drastic measures—such as suicide. And when someone like Yoo-jin finally does put their career on the line, who’s willing to follow?

Neither woman is the type to quit. We meet So-hee in the dance studio, repeatedly practicing a spin move she can’t quite master despite constantly falling. We watch Yoo-jin tirelessly knocking on doors to hold the real people at fault for these deaths accountable, even as they all exonerate themselves by reiterating how someone else is forcing their hand and thus the “real” villain. And both performances ultimately bleed into each other. Si-Eun takes us from a young woman with nothing but promise to a broken soul unable to fathom how everyone could let themselves waste away for nothing. Doona from an expressionless taskmaster going through the motions to an impassioned advocate dictating them. Life to death to life anew. Together they might win. Not today. Maybe tomorrow.

Jung’s script and direction keep things grounded while ensuring everything she shows us is necessary to the bigger picture. Little moments like So-hee’s manager (Hee-seop Sim) hearing someone scream at her and actually stepping in to scream at him rather than her stick with you. So, too, do the heartbreaking instances like So-hee’s cry for help to her parents being left completely unheard in a futile attempt to have it just go away. And while you may think a total shift in perspective halfway through is distracting, think of the film in Law and Order terms to understand why. We must first see the problem to know that one exists. That way, when Yoo-jin finds herself on an island alone, we know she’s correct to keep pushing forward.

Next Sohee closed out the Fantasia International Film Festival.