In order to make the rote activity of yearly list-making more interesting, there seems to be some need to frame it around a greater narrative. Take your pick: that the doomsday clock is ticking on cinema; that the medium can’t compare to what’s going on in that certain dreaded, instant-reaction-friendly entity (hint: rhymes with smell-o-vision); that one nation managed to produce a great output while others floundered, etc.

Yet in trying to get this list down to 10 (or 16, technically speaking) I had to exclude a number of worthy titles like David Mackenzie‘s muscular male weepie Starred Up, Yann Gonzalez’ vulgar yet sentimental You and the Night and Alain Resnais’ moving swan song Life of Riley, amongst others. Basically what I’m saying is that I see no reason to complain. Cinema is alive and well!

As per usual, to stick to the idea of “my personal year in films,” I’m going to include titles that haven’t seen a North American release yet.

Honorable Mentions

10. Whiplash (Damien Chazelle)

For every exquisite composition or edit, Whiplash occasionally gives in to ham-handed or clichéd images (yet another one of those oncoming car crash shots) — yet as simply part of the film’s utterly mad rush, even they gain a kind of charm. When taken as of a piece with what’s essentially a psychopath’s coming-of-age (not the quasi-inspirational tale of “what it takes to be great” that’s being widely interpreted as condoning emotional abuse), it’s wholly apt. Even the concluding musical number, which initially seems like the cathartic triumph, is an act of anger and revenge.

9. Listen Up Philip (Alex Ross Perry)

The asshole, the asshole’s instigator, and the asshole’s victims: certainly all regular players in an “edgy” indie, the kind self-satisfied with its own sense of confrontation. Though through a structure where they’re all given their own space and thus thoroughly humanized — if not entirely forgiven — Listen Up Philip continues Alex Ross Perry’s exciting revitalization of a seemingly stillborn subsection of American cinema. A special credit is due to Kate Lyn Sheil’s brief appearance, which feels like a lost dream sequence from Love Streams.

8. Jersey Boys (Clint Eastwood)

Seemingly found on a series of contradictions — classical, yet digital; self-referential, yet melancholy; a musical, yet directed by Clint Eastwood — Jersey Boys still remains a wholly mysterious film to me. And all of this couldn’t be more exciting coming from one of American cinema’s elderly masters, who I assume will live to Manoel de Oliveira-age, churning out one radically unfashionable masterpiece after another.

7. Jauja (Lisandro Alonso)

After seeing Jauja, I believe I remarked to my cinephile compatriots that it was the first Lisandro Alonso to work thematically as well as formally — that, finally, his considerable talents went towards more than a prankster-ish slow-cinema exercise. A couple of months of later, I honestly forget what the “meaning” I derived from the film might have been, though I think it was some nonsense about lineage and the passage of time and what not. But I don’t believe that really matters, for what’s made Jauja stay with me is its pure beauty — the synchronicity of light, movement, landscape, and even the physical presence of its star.

6. Boyhood (Richard Linklater)

Guess what? The ever-risible Ernesto scene, in which the long-suffering character of Mason’s mother is thanked by the Mexican laborer who she apparently steered into the glorious life of restaurant management through the mere suggestion that he go to school some two or three years earlier? It comprises about thirty seconds of a nearly three-hour film. Get over it.

5. The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson)

Whereas Wes Anderson’s past films occasionally shifted towards pathos in an awkward manner, The Grand Budapest Hotel naturally embeds it throughout. Or at least comes this realization in the gut-punch of its last five or so minutes, in which all of the well-noted Anderson traits come to feel like an embodiment of memory, all co-existing with what’s easily his funniest film since Rushmore.

4. Welcome to New York / Pasolini (Abel Ferrara)

Two men of power and thus two representations of one of Ferrara’s key themes: the politics of everyday living, itself heavily indebted from Godard. Stylistically, they couldn’t seem more different. Pasolini is far more Ferrara-like with its plentiful number of superimpositions between fact and fiction, and Welcome to New York brings the anomaly of matter-of-fact, long-take master-shots of acts both mundane and awful. Yet ultimately each comes back to personal hells, self-projection, and an upending of each lead’s assumed class relations.

3. The Immigrant (James Gray)

To use the pejorative of capitalization given to seemingly any film willing to take itself seriously, yes, The Immigrant has — forgive it — Grand Themes and Big Emotions. Of course James Gray, who goes as far as to publicly proclaim his place as one of the last few earnest American filmmakers, manages to actually carry the weight of his ambitions. This may be due in part to how, while typically emphasizing the subjectivity of his main characters, Gray allows his most nuanced supporting character, Joaquin Phoenix’s Bruno — with the actor’s remarkable skills in portraying someone never comfortable in their own skin — to become just as sympathetic as the fallen woman at the film’s center.

2. Goodbye to Language (Jean-Luc Godard)

I raised this idea with regard to Clint Eastwood, but might as well expound upon it slightly here. What we think of when bringing up a “late work” is either, in the case of the aforementioned, a decidedly unhip picture, or the death-is-rapidly-approaching dirge. Yet “late” Godard (a designation I believe have been given to everything from In Praise of Love onward) is so unlike anything else, and especially in the case of Goodbye to Language, so ultimately optimistic, that it defies all labels. And this may all be because it’s willing, at its end, to pose this question: “What do dogs dream about?”

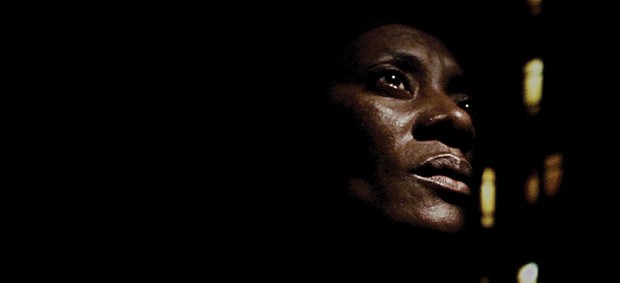

1. Horse Money (Pedro Costa)

I attempted to write about Horse Money immediately after seeing it back in September. I think I did a fine job, considering the hectic strains of festival life, yet I don’t believe that I in any way did justice to just how different the world felt coming out of it — how surreal and inappropriate the gaudy, space-themed halls of the Toronto multiplex hosting the press screening seemed after spending 100 minutes in what seemed like a mix of hell, purgatory and probably some other dimension of the afterlife not even comprehensible to man. If only I could find the right Wire lyrics to quote…