Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2023, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

I’m not much for introductions, but I have a confession to make; a difficult one, and maybe disastrous to my career prospects in the cat-eat-cat land of the media commentariat. But to anyone who knows me, the secret is already out: I am not very cool. I don’t live in a major urban center or have regular access to any hot arthouse theaters; I don’t travel the festival circuit and bump shoulders with the film critics you know and love. I don’t keep track of what’s new on Netflix or Prime or wherever. I don’t even get out much, really, except to walk my dog. When sleepy dark December rolls into town each year, most often I’ve barely seen more than a couple dozen films actually released during the past 12 months, and liked only a fraction of those; I’ve never seen enough, and certainly not enough good ones, that when I’ve been asked to submit a yearly top 10 list any answer I could give felt remotely honest.

But that’s not to say I don’t watch a lot of movies. I try to watch something new every day, whether it’s a full-length feature or a cartoon short, and scribble down some thoughts on my Letterboxd. If I can’t see something playing near me––always my preference, especially for the slower more cerebral fare you need to be trapped in a theater with a few other fidgeters to truly appreciate––I’ll pick through streaming back catalogs or search up a film on a whim. A favorite director or writer, a subject I’m interested in, something a friend or person I follow is passionate about. So my cinematic diet is myopic and a bit random, I guess, inasmuch as it mostly reflects the whim to watch something fitting my mood after work and not a responsible critic’s duty to sample a bit of everything or investigate the talk of the town. As far as the consumption of art goes I am a petty and temperamental animal, enslaved to my passions and prejudices, and not so much a being of higher consciousness or scholarly discipline. Maybe you’re the same. Hence, a list of my top 10 personal virgin viewings of 2023, instead of a yearly debut roundup.

With the long-winded apologies out of the way, I’d like to thank Jordan and Nick for giving me, as they have since 2016, a platform to more or less freely spew my thoughts on the medium I love in whatever strange, picky way I do. I am shocked and humbled any time words I write find a willing audience, let alone one of people who ought to know better. If you’re taking the time to read this, whoever you are, whether you know me personally or not, I hope you find something to chew on for a bit in this list of films that stuck out in my memory looking back at 2023. I hope the list is not boring, and that it gives the accurate impression of a messy, impulsive, ridiculous, self-contradictory, warm-blooded human being’s tastes and thoughts on art, as opposed to the “thoughts” of a content-sorting algorithm. If you discover any films that turn out to mean something to you as a result of reading this, or you’re happy to see a personal favorite get some acknowledgment, I’d love to hear about it. If you fucking hate one or more of the films on this list, if it kickboxed your eyes and offended your sensibilities to the point that you believe the world would be measurably better off without it or its admirers, and you’ve done the pitiless calculus to prove this… well, I’d be curious to hear about that too. Anything’s better than leaving you numb and indifferent. As somebody famous once said, the opposite of love is not hate; it is indifference. All I can ask, and all art can ask, is to just barely poke through that stinging shroud of indifference we all learn to live with every day.

10. Legend (Ridley Scott, 1985)

Sir Ridley’s infamous 80s bomb, an epic fairytale channeling equal parts Tolkien, Milton, Cocteau, and stoner decor, may be his most deeply flawed almost-masterpiece––to call it a “good movie” might not even be strictly accurate––but it is fascinating. His fourth feature film after the all-timer debut run of The Duellists, Alien, and Blade Runner, it exhibits every ounce of those films’ painstaking visual worldbuilding, thematic ambition, and unrivaled genius for practical effects. It’s never more astonishing than in the baroque, Dante-channeling subterranean labyrinth of Tim Curry’s crimson-red Satanic villain, himself a terrifying presence of both otherworldly baritone malice and oddly childlike vulnerability. The film is a lyrical, noble attempt––albeit one whose pursuit of broad, mythic archetypes flirts a little too frequently with tackiness and incoherence––to construct a popular work simultaneously hyper-modern and primeval. Its characters’ language and desires draw from premodern European folklore and childhood games of pretend, but they navigate cutting-edge technical spectacles from the master of the form in his prime.

It also, of great interest to me specifically, forms a provocative dyad with Blade Runner through the anchor point of the unicorn: Legend’s Genesis-inflected setting declares the mythical beast the symbol of dawn and innocence, revealing whole new layers of intent in the visions Rick Deckard sees, in his nocturnal Babylon, when he closes his eyes. Through fantasy and science fiction, the beginning and end of history are in direct conversation, one yearning for the other across the gulf of collective memory; try bringing that up the next time someone says Scott’s not an auteur. (Ironically, though, I strongly recommend the Tangerine Dream-scored US theatrical version over the plodding director’s cut with Jerry Goldsmith music; Goldsmith is a genius of course, but his attempt to score the film as a more conventional fantasy adventure pic just doesn’t match the dark, ethereal fugue state that Tangerine Dream correctly sees in it.)

9. Cruising (William Friedkin, 1980)

Friedkin’s grime-caked Manhattan thriller about the hunt for a killer of gay men would have already made my yearly list even before the Hollywood maverick’s unfortunate passing in August (on my birthday, no less––that’s a bad present). The final minutes do something I’ve simply never seen before: they ignite the film’s carefully constructed gritty realist verisimilitude like a backward-traveling fuse, exploding the preceding hour and a half––turning its insides out, inverting its entire semiotic logic––and, somehow, it works. What was passed off almost convincingly as the cold, objective gaze of the crime procedural, we suddenly realize, was the subjective gaze of a character we thought we were only observing––not experiencing. If that sounds a little abstract, it’s because this film’s ending recontextualizes the rest of it so radically that I cannot bring myself to spoil it if there’s even a chance you haven’t seen it for yourself. I will only say that Cruising wears its Pacino 70s crime genre getup like an unnervingly convincing skinsuit, beneath which lurks a violently interioristic film whose expression of raw pain is still as rattling and radical as anything seen today––and contrary to first impressions (and contemporaneous criticism), it courses with complex empathy for queer experience.

8. Candyman (Bernard Rose, 1992)

Absolutely not the Nia DeCosta/Jordan Peele reboot from 2021, though that film’s insinuations about the titular character’s murderous rampages as a form of “racial healing” did usefully predict new moral lows of elite radical posturing as of 2023. Rose’s film––fortunately for itself, and unfortunately for the world it reflects on––is timeless. One of the only American horror films to truly get Kubrick’s The Shining, it’s a cerebral high-angle cruise through the scarred, crisscrossed roads of America’s collective unconsciouss––its racial trauma, its burdens of history, and the taboo desires lurking beneath its steep sociological divides––and the maltreated urban landscapes which embody them. True to its origins in Clive Barker’s gifted imagination, the film is loaded with provocative psychosexual and political subtext but never deigns to let didacticism stand in the way of poetic ambiguity or a raw nightmare image––bees swarming on human skin, for example, or a killer’s messages painted in shit on a desecrated restroom wall. Tony Todd’s seductive growl as the untamed boogeyman avatar of black pain and rage makes one of the great horror villain performances of all time, and Philip Glass’s unlikely score––among his best original film projects made without Godfrey Reggio––has just enough flavor of Verdi via Wendy Carlos to further cement comparisons with Kubrick’s horror masterpiece.

7. Sing a Song of Sex (Nagisa Oshima, 1967)

Like all normal high schoolers weaned on Neon Genesis Evangelion, I watched In the Realm of the Senses in my senior year out of pure curiosity. (Did you know Nagisa Oshima is an Eva character’s namesake?) My conclusion: if they showed that film in sex ed classes, abstinence would be much more popular with American teens. For a filmmaker so famously obsessed with sexuality, Oshima’s engagement with the subject is almost perfectly anti-erotic: he sees it as human expression in its most uncompromised form, as many do, but his view of humanity––ever overshadowed by the great political failures of the 20th century––is none too affectionate, to put it gently. Oshima’s furiously angry 60s films were a surprise (re)discovery for me this year, and Song of Sex is the one I’m most unable to get out of my head.

It’s an icily beautiful, visually and thematically dense tour of the student left through the eyes of a disaffected bourgeois boy’s club drifting aimlessly about “the movement,” hunting for nihilistic thrills and easy sex, whose glib sociopathy and violent fantasies in contrast with the film’s formal beauty feel like an early take on A Clockwork Orange. Through smug opportunists and naive ideologues all chirping a hundred tunes about liberation, Oshima paints a delicate, free-associative nightmare portrait of the vacuous postwar subject and a movement fatally unmoored from its own land’s legacies of rapacious violence. Huge, ornate panoramic shots (Lawrence of Arabia is namedropped repeatedly) are contrasted with myopic soundscapes to illustrate through raw sensory impression its characters’ rejection of their own world. The final act turns to a succession of crimes, degradations, and dream logic setpieces before ending abruptly, leaving the audience feeling teased and violated. It’s confounding, surreal, and violently unsettling; it’s clawed and burrowed its way to a half-dream nest in my brain that I don’t think it’s likely to vacate any time soon.

6. Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957)

This one’s just so obviously among the greatest achievements of 1950s Hollywood that I’m not even sure I have anything constructive to say about it. I guess I’ll start by saying I’ve never liked Billy Wilder as much as most; I find him linguistically accomplished but visually unimaginative, and for all the talk about his films’ jarring cynicism they lapse into award-friendly sentimentality more often than I’d like. Sweet Smell of Success is like Wilder’s The Apartment with the full courage of its nasty, cynical convictions, and a dagger-sharp cinematic eye to boot. Ernest Lehman and Clifford Odets’ screenplay is simply one of the best-written of all time, as sopping-wet scummy and sleazy as anything imaginable under the Hays Code, an utterly acerbic take on the sold souls of hustling New York media folk whose ingeniously seeded twists never overwhelm the moment-to-moment vividness and verisimilitude of its characters and milieu.

Its every other line is a metaphor, witticism, or turn of phrase so opulent you could just as well label the whole thing a prose opera. (Elmer Bernstein’s lush jazz score helps on that front.) The words are enough, but James Wong Howe’s expressionist cinematography heightens the register even further, revealing the film’s cast of egocentric schemers as dwarves and titans scrabbling for stature under the skyscrapers in a nine-circled showbusiness hell. And have the times really changed? Hell no: you could remake the film for the age of the influencer with minimal alterations, get David Fincher to direct, and have an instant hit on your hands; but that’s provided any screenwriter working today could match Mackendrick & co’s verbal mastery. This, I doubt.

5. Cutie Honey (Hideaki Anno, 2004)

Finally checking this film off my watchlist in preparation to review Anno’s Shin Kamen Rider––which I did not adore––was both a relief and a disappointment, of sorts. Turns out my more tempered responses to Anno’s recent output aren’t just me getting older: Japan’s great pop auteur has also changed. Where Shin’s formal experimentation felt workmanlike and IP-reverent, Cutie Honey––Anno’s first venture into silver-screen retro pop culture reimaginings, without the “Shin” label––zings and zips with manic energy across the director’s dizzying emotional range, refreshingly unconstrained by any pretense of acting respectable. It’s a delirious high camp highwire act embodying an otaku’s half-ironic affection for retro kitsch, a film where the throat-snorting pleasures of bad special effects and corny superhero dialogue play ball with wildly creative extensions of the form born from a master animator treating “real” camerawork as a 2D cartoon, and the bubblegum escapism of yesterday’s male-constructed hyperfeminine pop rubs shoulders with the quiet loneliness of the twenty-first century’s working woman. (It’s way better than Barbie!)

The film sits comfortably beside other 2000s “live-action cartoon” digital experiments like Speed Racer, Shaolin Soccer, Spy Kids, etc. but for my money also stands above them all: out of every filmmaker to try on the style, Anno is simply the best cartoonist. His alchemic tonal fluidity lets the film totally blindside its audience when it stops dead in its tracks to contemplate a tiny, intimate human interaction; the psychedelic climax pulls out classic Anno motifs of apocalyptic imagery and Gnostic intonation beside deeply felt introspections on love and loneliness. I’m not entirely sure the indubitably nerdy, indelibly human passion of the artist who made this orgiastic love letter of a film still exists in the culturally enshrined hitmaker who runs his own studio and inks contracts with Amazon––but I want to believe.

4. The Overcoat (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1926)

I saw this unfortunately obscure, morbidly beautiful Soviet silent film with a Shostakovich-inspired score performed live by a good friend (lovely!) without English subtitles in a predominantly Slavic crowd (alienating!) with only a Wikipedia summary’s worth of knowledge of the Nikolai Gogol story it’s based on (on me for being a philistine!) seated behind a woman who pulled out her smartphone every couple of minutes to make Instagram posts about the film she was in the middle of watching (the pits!). This means my ranking is tentative, maybe even a bit of a lie, until such time as I can see the movie again with the words on the screen in my own language. But it should tell you how captivating the film is in visuals alone that I include it this high on my list.

Shot heavily in the frozen, freshly revolution-blasted streets of Leningrad or else on shadow-soaked painterly sets, the film is a gothic tragicomedy with a somnolent airiness and a visual palette that warrants, in my book, the most generous kind of comparisons with Wiene, Dreyer, et al. But where their European expressionist contemporaries shot human faces and figures in the statuesque style of their gorgeous sets, young upstarts Kozintsev and Trauberg shook up their aesthetic foundations by looking to Hollywood as well: the actors in closeup move and emote with an undignified, semi-improvised vivaciousness that sets the film instantly apart from its Euro cousins. Curls of the lip, twitches of the hand and wagging of the tongue inject messy, devilish humanity into the tale of a middle-managing shlemiel with dark dreams of bourgeois decadence.

It’s said that the directors’ desired star was none other than Charlie Chaplin himself, but in a cruel story of the state’s violence against art, the American and Soviet governments conspired to forbid such a transnational collaboration of citizen artists. Even without Chaplin, the artists’ clear admiration for America’s physical comedy brings their stately nocturnal images to restless life, giving the whole thing the feeling of a Russian witching hour where ghosts dance and rave beneath the frozen moon. I’m kind of appalled that Kozintsev and Trauberg are so widely forgotten: judging by even a cursory look at this film, they should be remembered as major figures of Soviet cinema.

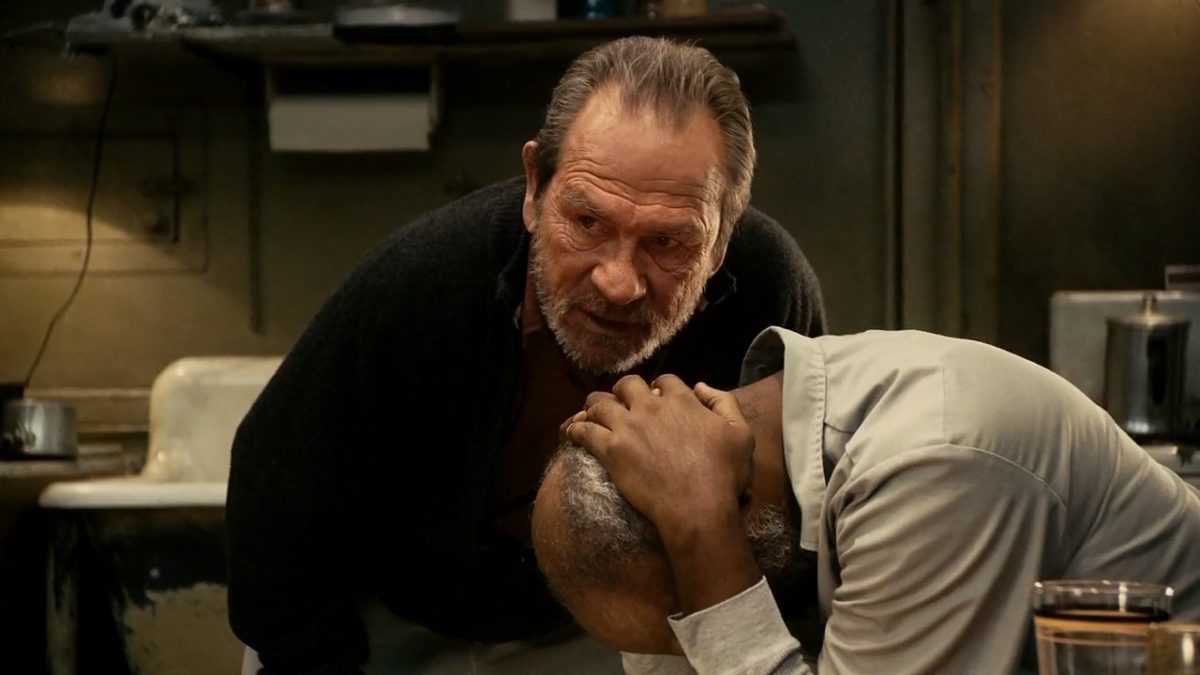

3. The Sunset Limited (Tommy Lee Jones, 2011)

Unlike Cruising, I did watch this one specifically in response to the death of an artist. Cormac McCarthy’s passing in June affected me enough, as someone profoundly impacted by No Country For Old Men as a teen, to go down a personal retrospective of all seven feature films adapted from his work. The Sunset Limited was the most rewarding discovery out of these. It’s a humble little film, an HBO adaptation of a stage play that feels exactly like what it is, but in the context of McCarthy’s corpus it’s a tiny gem that illuminates all that surrounds it.

Here, in two nameless, diametrically opposed men richly embodied by Jones the director and Samuel L. Jackson, McCarthy lays out in his barest terms the war between faith and despair that animates so much of his work of the 2000s especially. Jones, a nihilist academic, has given up on the world and life; Jackson, a penitent criminal of firm Christian belief, rescues him from suicide and tries every rhetorical route to dissuade him from oblivion. It’s characteristically bleak, of course, but Jackson’s character is also allowed to be one of the most charismatic and iron-willed voices for love, hope and justice to exist in McCarthy’s savage literature; the admiration with which he is portrayed and the gregariousness he is allowed to exhibit are only more powerful surrounded by gruesome McCarthyan fatalism.

The language of their verbal duel is as rich as one would expect, but in contrast to the cold, loveless, mannered verbal hellscapes of The Counselor or Stella Maris, these characters aren’t pure mouthpieces for philosophical ideas and academic namedrops: in between lecture points and parables they’re allowed to joke and laugh (with jokes that are funny!), to discuss chili and beer, to prod one another over racial anxieties and political correctness. To be characters, in other words, and not just the archetypes McCarthy’s verbal constructions sometimes find themselves reduced to. This minor, ambivalent work might be the most fitting epitaph to the major American author, and Jones realizes it respectfully and organically on the screen with a camera that quietly probes the two characters’ shifting reactions and performances up to the task of humanizing them. Necessary viewing for McCarthy admirers.

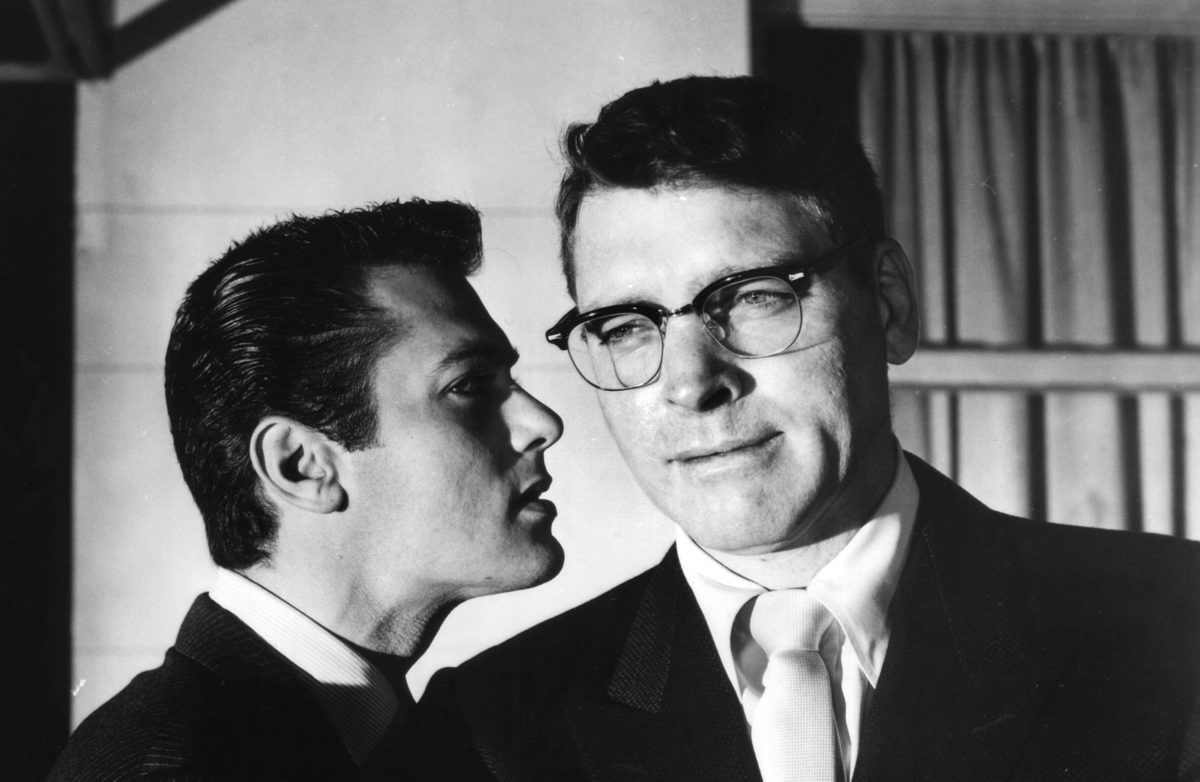

2. The Strange One (Jack Garfein, 1957)

To this day my most personally gratifying experience writing for The Film Stage was when seven lightning-fast years ago, as a literal infant child, I interviewed Method mastermind Jack Garfein at the Criterion offices. Now my biggest regret will be not having tracked down the first of his two too-rarely-seen feature films prior to that interview. Even more than his eerie, ambiguous trauma film Something Wild, the easily misunderstood Strange One certifies that Garfein should have become a major director if, like Orson Welles, he was not exiled by the Hollywood studio system for being too radical too soon. And the film is radical: adapted from a Calder Willingham play, it takes deadly aim at the subconscious mores operating a Southern military college beneath its facade of law and order, where the baroque disciplinary structures of the armed state institution conceal a sadomasochistic economy of secret desires and cruelties––one where the promise of punishment ensures the perpetuation of crime.

A young Ben Gazzara hypnotizes as Jocko de Paris, a sadistic sociopath turned unlikely victim who exploits even the ostensibly egalitarian, modern rules of the institution to his benefit – until his little games push its savage contradictions to the fore. The specter of queer repression hangs heavy over the film, which juxtaposes the physicality and hysteria of Method performances against the rigid geometry of its fictional academy––sharp right angles, blank white walls, and black iron bars, a purgatorial space that comes increasingly to resemble an asylum as Jocko’s provocations set off a chain reaction. But Garfein and Willingham needle in the subversion beyond just sexuality: after Jocko finally pushes his peers far enough to drop the guise of civility, the film culminates in a nightmarishly shot reenactment of an American lynching, its explosive racial subtext made all but explicit in a scene on a segregated train car that Garfein had to literally sneak past Columbia Pictures.

The film’s psychoanalytic tirade against US military culture and the national id it conceals is jawdroppingly dark and raw for 1950s Hollywood, prefiguring no shortage of intellectually cheaper, broader films in the Vietnam era – and, in its insinuation of state disciplinary structures tacitly in league with their own violators, of Michel Foucalt’s seminal Discipline and Punish published nearly two decades later. Had Garfein continued to make films into the 1960s and onward, it’s almost a certainty he would have produced masterpieces. As is, The Strange One and Something Wild deserve to be seen and studied as the radical challenges to Hollywood that they were, and still are.

1. Fateful Findings (Neil Breen, 2013)

Many, many, many filmmakers try to emulate David Lynch, his uncanny juxtapositions of middle-class domesticity with the violent and bizarre, the trademark dissociative haze that makes his work otherworldly and unforgettable. Only Neil Breen is truly unhinged enough to succeed. If auteur cinema is the culmination of formal choices to produce a complete imprint of one artist’s idiosyncratic view of the world, there’s simply no arguing the auteur credentials of the cult favorite writer/director/producer/actor/caterer/financier from California ––and Fateful Findings is his magnum opus.

Steamrolling over conventional representations of time and space, over narrative logic and any recognizable artistic impulse in any one of his many roles behind and in front of the camera, Breen’s suburban magical realist thriller follows the romantic exploits of an author, hacker, psychic and sufferer of an unspecified psychotic disorder––played, of course, by the man himself––as he reconnects with his childhood sweetheart while setting out on a spirit quest to unravel “the most secret government and corporate secrets” by abusing a series of laptops. Again and again, Breen’s creative choices baffle and enthrall. Important dialogue is almost always spoken twice in the same scene. Monotone conversations so distant from recognizable human behavior they make Tommy Wiseau seem like a regular guy are punctuated by characters staring at each other in dead silence between lines––often for unbearably long stretches.

When a mid-snack Neil spills his plate of raw spinach in front of his lover, the spinach gets a reaction shot before he does. Whenever vaguely supernatural forces are about to enter the film, a Windows 97-like ghost fart animation wafts through the exact horizontal center of the frame, accompanied by a single distorted wail that might very well be Breen’s own voice. The same James Horner-esque soft pan flute riff plays on the score when Breen meets the love of his life, when he’s lying comatose (and pantsless) in a hospital bed, and when his wife kills herself with drugs. Just when the film threatens to slip into monotony, it pulls a politically incendiary climax out of nowhere that catapults it into the most certifiably insane cinematic documents this side of ISIS propaganda.

Each of these decisions in isolation could be chalked up to (hilarious) incompetence, but taken all together they add up to something inexplicable. Comedians like Tim & Eric try to emulate Breen’s uncanny “cringe” style, but having tasted the fruit of ironic self-awareness they’ll never fully succeed––or be half as funny in the attempt. I did not feel more delighted, or more like I had tripped into a parallel universe, watching any other film in 2023.