In the new documentary Factory to the Workers, the men and women of a doggedly socialist metal factory in northern Croatia struggle facing up to the realities of our free-market society. Observantly and impartially directed by Srđan Kovačević over the course of five years, it is the story of an unravelling, beginning in 2015 as workers of the ISAT Prvomajska factory in Ivanec prepare to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of what remains their defining triumph: after a failed attempt at privatization in 2005, the workers occupied the building and restarted the production of tools. Their actions landed them in court, yet they somehow, shockingly won and essentially took over. Those inspiring events remain, as an opening text in Kovačević’s film explains, the only example of a successful factory takeover in post-socialist Europe.

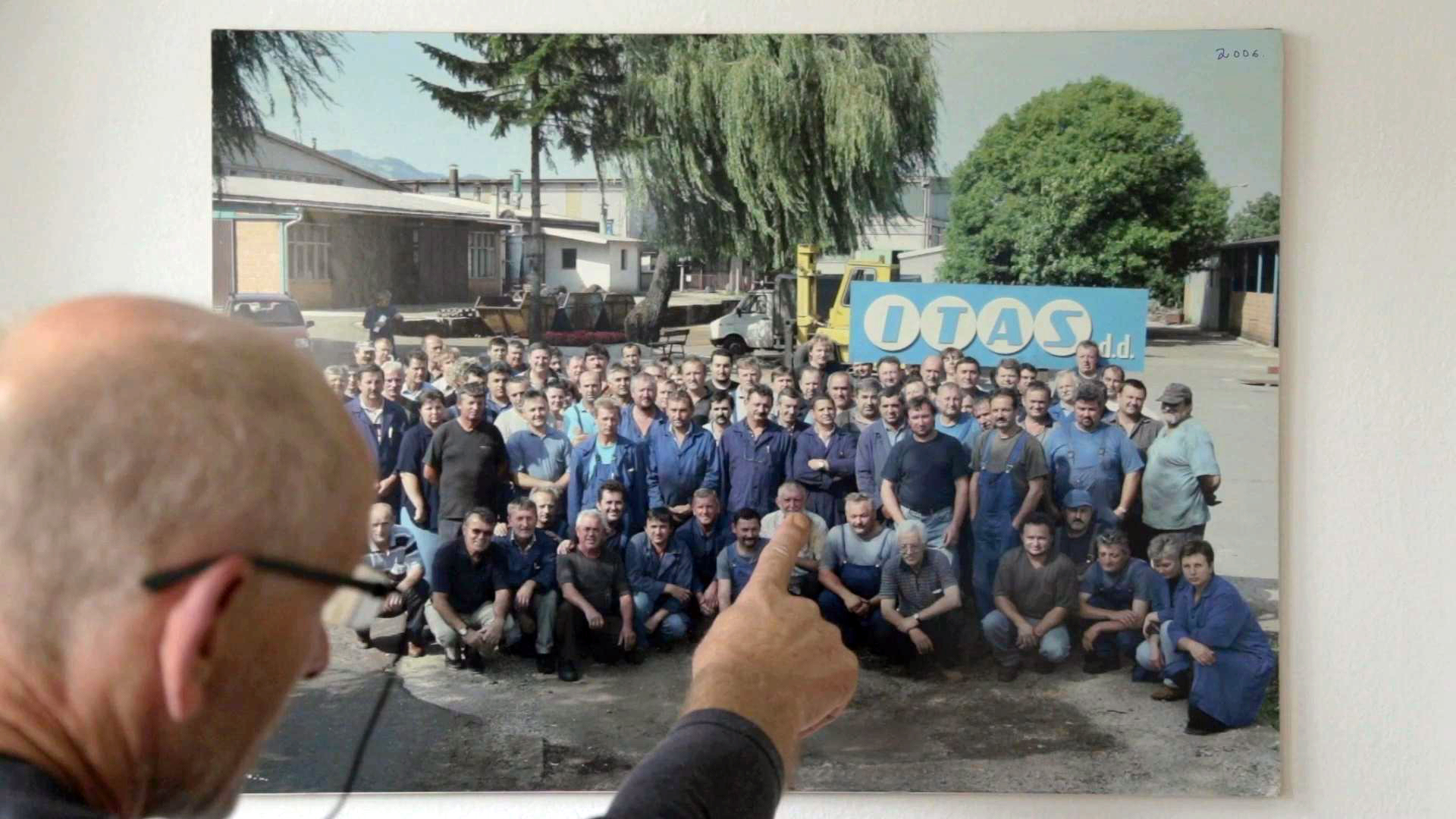

The pride in that achievement is as palpable in Factory to the Workers as it is increasingly contentious. Take the words of Dragutin Varga, original leader of the occupation who remains a spokesman for the workers, as he makes one of his many addresses to his younger colleagues: “The point of all this is that the young workers realize that everything we, the old workers, are doing right now, we are doing it for you … If we all are owners, this is a sustainable project.” Problem is, there aren’t many of that old guard left. In an opening shot, Kovačević shows Varga looking over a group photo of him and his fellow occupiers from 2005, many if not all of whom had grown up in the former Yugoslavia, and noting, without irony, how the majority have either retired or died. Varga is determined to keep the flame alive but the factory’s newest workers are more concerned with simply getting their wages on time.

Kovačević’s film thus becomes a study of a generational and ideological divide, but it’s also an example of how a once-thriving factory can be marginalized in its attempts to compete in a globalized economy. Most of ISAT’s business is done through German and Japanese clients but their management is growing sloppy and their talent being drained—apprentices who have been trained by ISAT’s skilled veterans are being cherry-picked by their rivals. “We are a nursery for our competitors,” one worker comments, distraught at seeing another trainee leave for better pay. Amongst this, Kovačević locates a power struggle at the top, between Varga (an inspiring orator with little experience of administration) and the suited executive director Božo Dragoslavić, the closest thing the place has to a boss.

The sense of a place out of time is also deeply felt. At one point Kovačević lets his camera linger on a faded picture of General Tito that still hangs on the factory wall—many of the older workers remain understandably nostalgic for that socialist past (for an equally engrossing meditation on Yugoslav nostalgia, look to Srđan Keča’s recent Museum of the Revolution). In another withering anachronism, the director also repeatedly returns to a mural being erected to celebrate ISAT’s decidedly past glories. It all culminates in a vaguely wry Wisemaneque rigor, most clearly in terms of its light-footed style and structure but also a clear sense of humility. Kovačević presents the older workers as inspiring but also blinkered and even naive. The younger generation, with all their frustration, come across as brash and short-sighted at first, yet the film is ultimately no less on their side.

Needless to say, there are islands of conflict to be explored between all those hopes and those realities, and we are never left in any doubt about how much skin these people have in the game. It is a thought-provoking paradox, similar in quite loose terms to American Factory, another allegory lodged between unstoppable force and immovable object. Meetings are conducted; rousing speeches are delivered; machines whirr and screech. It is uplifting at the off, dispiriting by the end, and never less than compelling.

Factory to the Workers screened at Doclisboa.