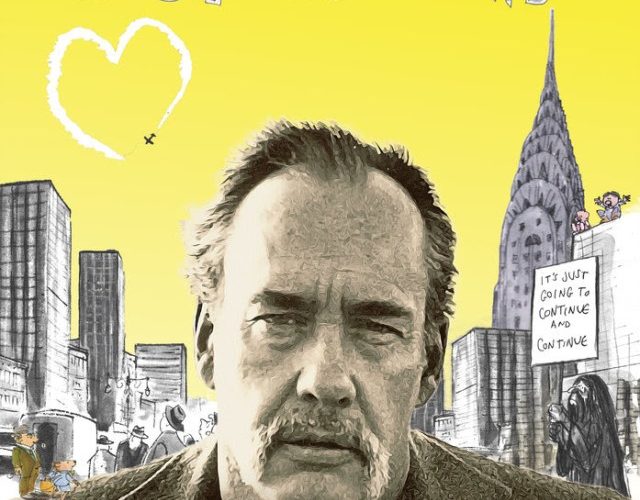

An intimate yet slight portrait of New York cartoonist, poet, children’s book author, New York Times op-ed contributor, and father to nine child, Stevenson: Lost and Found captures quintessential oddball and Yale-educated life-long freelancer James Stevenson. The film is a loving tribute to Stevenson who passed away in 2017 at the age of 87 as director Sally Jean Williams combines the recollections of colleagues from the New Yorker and the New York Times, his spouse Josephine Merck, and many of his children who recall a father preoccupied with work to the point he thought Skittles were an acceptable lunch.

The author of the Times’s Lost and Found Vanishing New York, his work takes a poignant turn (as does the film) as his health declines, although he continues to produce work like City Footprints in the Snow which bring a kind of joy as they celebrate the spirit of a city he observed largely as an outsider from his home in Connecticut. Early in his career, he started his day sequestered away from his family, drafting 15 jokes, and when he had to, he’d commute into the city to sell his wares. He soon discovered rather than just writing jokes he could make more producing cartoon works parodying the malcontent middle-aged professional male who never quite found his place in the world. A New Yorker cartoon image finds this figure in front of a movie theater asking the box office attendant how much he’s going to hate the movie.

Stevenson, a larger than life figure of boundless creativity, probably would enjoy this tribute, however minor it is. We do get to see the master work late in life as he finds love with Josephine Merck, also a late-career artist. His first marriage, which produced nine children, ends in tragedy and the film touches upon the death of his first wife and the reasons that drew them apart without dwelling in the sorrow. This is perhaps encompassed best in a metaphorical drawing of a ladder that James presents towards the end of the film, when battling a form of dementia. “Man is like a ladder,” he says, “strong in the middle and missing a few rungs towards the end.”

Williams is given intimate access without overstaying her welcome in the process of making the documentary, which at times feels like an often too polite exploration of Stevenson’s life, focusing on his art from the concise humor of his New Yorker cartoons to his children’s books which celebrate figures not typically celebrated in that form of literature. Overall, Stevenson: Lost and Found also doesn’t overstay its welcome, approaching a subject who led a rich life without much mystery. The film effortlessly employs watercolor animation in tandem with narration by David Furr from Stevenson’s journals, filling in the gaps in the film’s talking head approach, which can grow tiresome after a while. The documentary is unexpectedly moving as Williams captures an engaging subject, an American original who viewed and parodied New Yorkers with the kind of comfortable distance required to make great art.

Stevenson Lost & Found premiered at DOC NYC 2019.