If co-directors Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt have done their job correctly, audiences will walk out of their new film Diamantino feeling they were impregnated (to use Iñárritu’s lexicon) with “candy that doesn’t make you sick.”

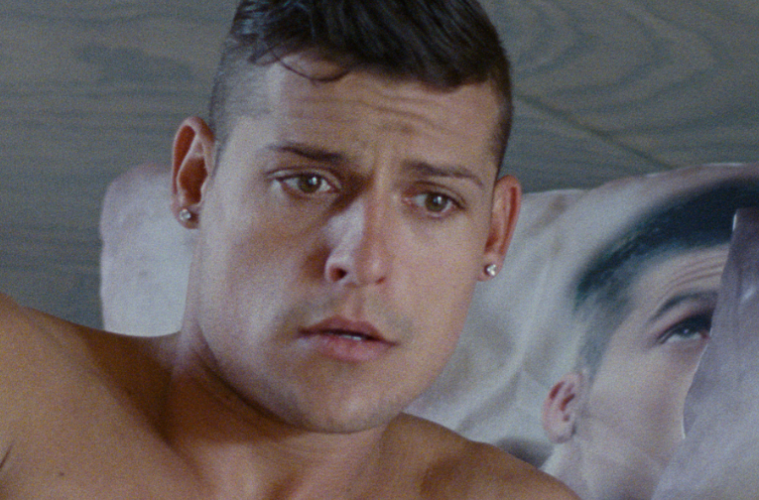

Diamantino (played by Carloto Cotta) has Cristiano Ronaldo-like fame, but makes a fatal error on the soccer field and loses his superstar status. Left with nothing but his good looks, Diamantino is revealed to be a bewildered and wide-eyed Forrest Gump for the 21st century; a century plagued with right-wing machinations for which the former athlete is duped into lending his image.

We sat down with Abrantes and Schmidt at the 56th New York Film Festival to discuss the political power of mass entertainment, how Diamantino defies categories by playing in Midnight and Avant-garde sections of film festivals, and how the comedy of Lubitsch and crude special effects of Cocteau shaped their modern fairytale.

The Film Stage: How would you feel if audiences approach Diamantino as pure entertainment?

Gabriel Abrantes: I think I would love it. I think Daniel and I came to film as entertainment, more so than an elite, fine, intellectual art. There’s this text by this philosopher Badiou… this is getting very intellectual to make an argument for entertainment. [Laughs.] “Cinema’s democratic emblem is its mass appeal.” That’s what makes it politically powerful. We’ve made lots of weird short films and with this film we had discussed making it funny and accessible to a large audience, not just to a cinephile audience. We have a huge respect for entertainment, and we think entertainment can be political and often is.

Daniel Schmidt: I think we also would like people to take away more than entertainment. A lot of the movies that excite us sit on that line or might be something purely intended as entertainment that we read in other ways. But I think this movie is certainly in that tension space of something that is a little bit more political, a little more experimental, someone described to me as “candy that doesn’t make you sick.” The film is still new to us and new to audiences, but it’s interesting to see how it’s been programmed in more avant-garde sections and then more quotidien, World Cinema sections. In Toronto it was in a section called Midnight Madness and there was cheering when there was certain kills or kisses. I think that for myself the varied response to the work is something that excites us.

At the New York Film Festival, Diamantino wasn’t in the Main Slate, but it played at the press and industry screenings. They usually only pre-screen Main Slate films and some documentaries, but your film and In Your Face were the only Projections films that screened early.

Abrantes: I think it was considered for the Main Slate, but then you know, however programming works out. Our friend was like “there’s no film that was in Midnight Madness and Projections and crossovers to the public” and we were really happy to be in Projections because it has to do with the film, because it is pushing certain aesthetic boundaries and trying to be entertainmart, but entertainment that makes you think and Midnight Madness which is about camp and kitsch and trying to make people scream.

Schmidt: I was also saying to someone how both those programs, these systems of ordering and categorizing films, I think programmers and certain gatekeepers are realizing, not to do away with these boundaries cause they can sometimes help find a new work that you like or whatever. But I think some of the horror festivals and some of the fantasy festivals are dealing with a sort of expansive notion of what that can be. It’s no longer like old white men making films about the poetry of light, or monster movies.

How is Diamantino different from your previous shorts?

Abrantes: It’s a little bit more of a human film, and the satire is more pronounced, and it deals with slightly more topical issues whereas the other films were in this more transhistorical wash of topics that may not have been as resonant to an audience. I did this film about particle physics which reaches fewer people.

I think before, there was a lot of stuff we would talk about, ideas about art that inspired the films, and we were always under the opinion these conversations would transpire to the spectator and the spectator would be in on our conversation. We understand now that a lot of the stuff we made over the years is obfuscated or obtuse, like it wasn’t of easy access. So a lot of our ideas got hidden behind the way we worked. In some ways we thought that was interesting that they weren’t like morals or messages painted on the film. I think in this film we wanted to make sure a lot of our ideas were understandable to people who weren’t from the same art school or taste.

Schmidt: And that doesn’t necessarily mean there aren’t aspects of the film that aren’t secondary. I think we hope the film is open to interpretation or allowed some kind of layers, but at least allowing people to enter on this first level of entertainment and puppies, and then people can enter in and ask questions.

When you’re co-directing, do you get on the same page in advance or day-of on set?

Schmidt: I think this project, and all the other projects, so much of the genesis of the film comes in the pre-production and the writing, and so much happens in post with editing and rewriting. This one had so much manipulation with the effects we were just talking about. Interpolating stock imagery or rewriting voice over. On set, it’s kind of the hectic, crazy crucible of everyone being there in this pressurized time-crunch.

Abrantes: I would also agree that in preproduction and writing a lot of the play between us is happening, but also in post-production. We spent twelve months in post-production which is long. Six months of it were just editing, him on a computer and me on another, going around to each other’s table. But we trust each other. We did the edit the same way we did the script: we had a structure and he took a bunch of scenes and I took a bunch of scenes and trade back. It was very organic in that way, it’s not a division of labor. There’s this huge element of trust. If there’s no time and we have to develop stuff on our own, we’re fine with it. But also the most fun thing is pitching ideas to each other and being censored by the other person and feeling awful about yourself. [Laughs.] Or the good part of that is throwing an idea maybe you wouldn’t take the risk on if you were directing alone and the other person is laughing or finds that idea smart and it really energizes you. Like the thing I thought was silly or stupid can actually be done.

There’s parodies of commercials in the film that play more like a parody of people who would parody commercials.

Abrantes: The only critique is literally presenting it exactly as it is. Which you see more and more, like with the Kavanaugh hearing that was parodied on SNL, which people said was epic and like, Matt Damon only repeated every single thing Kavanaugh said on TV the day before, which is very strange to me. It was that moment of history where comedy becomes reality which is very depressing.

Were you channeling Lubitsch with satire in the film? Also your use of crude, amateur special effects (no judgment intended) reminded me of Cocteau.

Abrantes: I think Lubitsch is spot on. He’s definitely one of my favorite filmmakers. To Be or Not To Be was a huge influence on me, but also his romantic comedies.

Schmidt: We were looking a lot at Trouble in Paradise.

Abrantes: Trouble in Paradise was a huge structural influence on the film. Also romantic comedies, but also like South Park as a structural, satirical way to deal with topical material. Au Hasard Balthazar by Bresson. The Donkey was a huge influence on us, how there are all these world pressures on this innocent “lamb of God.” That the donkey is innocent to these pressures.

I love effects in early cinema from Méliès to Cocteau; all of Cocteau’s effects had a big influence on me. And then all the way to 2018 tutorials from a kid in Sri Lanka using After Effects, and I’m trying to follow along because some of the effects we do ourselves, some are a professional company, the more complicated 3D stuff. Then some more popular stuff like Minority Report or Iron Man for the more holograms. It’s from a whole range of things.

Schmidt: I hope the movie becomes more than a pastiche of those things.

With the character Diamantino we wanted to show someone’s extreme proficiency might be based on an extreme deficiency. We were inspired to show that by two David Foster Wallace texts. One is about Roger Federer called “Roger Federer as Religious Experience.”

To paraphrase, “Today the moments that give us faith are these sports stars who are doing a technical, aesthetic activity that they do so well that the rest of us can’t do.” And art no longer does this because we’re not impressed by how people paint anymore or how people sculpt, it’s not as technically impressive. There’s that quote of “well, my kid can do that.” But in sports, your kid can’t jump in the air for a whole minute before they dunk or whatever. So seeing that impossible feat on a court or on a field makes you subconsciously believe there’s is a deity or something because it seems possible that this semi-divine human is doing this semi-divine thing.

The other text is about Tracy Austin. Foster Wallace reviewed her autobiography after she quit tennis, got into an accident, broken her bones, etc. and he had this impulse to read about what’s the secret her genius like “why didn’t I have it?” and he reads this whole book and it’s the dumbest book he ever read and it makes him tragically depressed. There is no answer though. Probably the lack of complexity and emotional complexity is probably the key to it. She didn’t know how to say anything else but “family is the most important thing” which she says like 300 times in the book. So he understood that the key was this emptiness.

I just watched Free Solo the other day. His father has Aspergers, and I don’t know if it’s genetic or not but he clearly has some emotional issues. They talk about how he has a girlfriend throughout the movie and that’s she actually worse for him and an impediment. It was so interesting to see this person who was able to climb 3,000 feet with no ropes and not have a fear of death, and they did an MRI and when they show him images that were supposed to make him fear, it was just blank. So he has some natural fear-inhibitor, whether it’s cultured or whatever.

Diamantino opens Friday at Metrograph in New York City and expands in the weeks to come.