It has been two weeks since the passing of Cormac McCarthy, the taciturn Southern gentleman widely regarded as one of the great American novelists of the last hundred years, if not all of American history. His prose poetry, as deliberate and lacerating in its construction as the lethal instruments often featured therein, evokes the country as an earthy garden of sin where men gamble their fates and faith before a pitiless, Old Testament God.

Where many great writers of McCarthy’s generation carved ever-deeper niches into the peculiar artifices of language and the 20th century’s assault of information, his lucid, imagistic narratives and spectacles of violent incident have often suggested the cinematic. His engagement with genre––Western, horror, neo-noir––interrogated American myths, peeling back their skin and tissue to reveal the stark existential queries beneath. McCarthy was fascinated by cinema from early in his career––he wrote several screenplays dating back to the 1970s, some of them based on his fiction, most of them unpublished––thus it’s almost a surprise more of his work hasn’t made it to the screen.

In total, seven McCarthy-derived feature films were released during his lifetime: four adaptations of his novels, one adaptation of a play, and two films––the first and current last––adapted from his original screenplays. What follows is an overview of each, taking into account their widely varying levels of success in translating the author’s visions to the screen, for diehards and the curious. His work, more widely read and celebrated now than ever before in a nearly six-decade career, will undoubtedly cast a shadow over cinema and the American arts for generations to come. For now, though, here is the core cinematic canon of Cormac McCarthy.

The Gardener’s Son (Richard Pearce, 1977)

McCarthy’s first original screenplay, a made-for-TV movie for the PBS series Visions, fits comfortably with his early novels: a slow, quiet, moody Faulknerian tale of familial and class conflict in the Reconstruction-era South inspired by an actual South Carolina murder case. Brad Dourif delivers a haunting performance as Bobby McEvoy, the peg-legged son of laborers employed by the industrialist Gregg clan, who grows increasingly alienated from his family and the company town as he nurses a mutual antagonism with the elitist and lecherous Gregg scion (Kevin Conway). The young Dourif excels in this role, his simmering anguish and rage inviting the audience to wonder if his private anticapitalist crusade is fueled by righteous fury or some more existential despair. McCarthyan themes of choice, fatalism, moral corruption, and crucibles of the flesh are all visible around the margins, and the dialogue is as rich as one would hope. An acid bluegrass score marks The Gardener’s Son indubitably as a product of the late ‘70s while simultaneously placing this period costume drama’s themes outside of time entirely.

All the Pretty Horses (Billy Bob Thornton, 2000)

The first semi-successful attempt to adapt a McCarthy novel for the silver screen, directed by Thornton and written by Silence of the Lambs scribe Ted Tally, was infamously plagued by production difficulties. An unreleased long cut faithful to McCarthy’s 1992 bestseller––162 minutes according to Thornton, who still possesses it––was drastically re-edited and re-scored at the insistence of Harvey Weinstein, with the intent of marketing it as a PG-13 romance film. The released cut may be a compromised work––its inappropriately sappy scoring and crude, sometimes confusing editing show the marks of Weinstein’s “successful” interference––but it’s not totally without merit. The basic shape and language of the novel are preserved, if truncated, making for some appropriately tense, ponderous exchanges which Thornton stages well. The cast is more than up to the task: Matt Damon acquits himself particularly well as John Grady Cole, the wide-eyed romantic and America’s last cowboy taught harsh realities by his journeys across the Southwest. Damon exudes just the right combination of charm, cunning, and naïveté to sell Cole as the rare McCarthy hero to challenge fate and emerge from his ordeals alive and (mostly) intact. Ruben Blades and Penélope Cruz also appear in Pretty Horses playing father and daughter; they would speak McCarthy’s words on the screen again years later in The Counselor.

No Country For Old Men (Joel & Ethan Coen, 2007)

The most famous and lauded of McCarthy adaptations also happens to be the best. Few regard his 2005 meta-genre novel––written as a screenplay in the ‘80s and turned into a novel much later––as the epitome of his work on the page, but by combining his literary sensibilities with their cinematic ones, the Coens produced an alchemy that still stands among the 21st century’s finest American films. Their most brilliant trick––one which no other filmmaker adapting McCarthy has yet reproduced––is tactically trimming the author’s verbiage to its sharpest tips while using the full breadth of their cinematic arsenal to capture the rhythm and meaning of his heightened prose.

Roger Deakins’ visual palette of panoramic Texas deserts, skeletal border towns, and black blood oozing into pale dust elicit the all-encompassing scope of the novel’s purgatorial images. An incredible soundscape supervised by Carter Burwell lucidly renders every gust of wind, click of machinery, and crunch of wood and bone amidst a near-total absence of score. Cuts by the Coens themselves mimic the staccato hail of McCarthy’s sentences, sometimes drawing out a simple action (a character constructing a makeshift trap, for example) with methodical, mesmerizing intensity and sometimes zipping coolly through scenes a lesser storyteller would linger on––never a word wasted at either extreme.

Javier Bardem became a global phenomenon (and Oscar winner) for his terrifying portrayal of Anton Chigurh, an implacable assassin envisioned by McCarthy as the quintessential man of tomorrow: a personification of the void, absent human emotion, morality, or even free will, who casually takes the lives of those he comes across in his pursuit of stolen drug money as though he himself were the agent of a heartless God. Equally strong, though, are the other two pillars in No Country’s trinity of protagonists: Josh Brolin as Llewelyn Moss, another charming and quick-witted cowboy who dares play the odds to better his lot in life; and Tommy Lee Jones as Ed Tom Bell, a weary small-town sheriff who pines for the gentlemen heroes of the old Southwest as his world warps and crumbles beneath him. Critically, the Coens also locate and accentuate the dry-as-bones humor in McCarthy’s work with their impeccable talent for bit-part casting and deadpan takes drawing out the bleak absurdity in these heroes’ attempts to outrun the inevitable alongside the sparks of the fire that keep them running. A masterpiece.

The Road (John Hillcoat, 2009)

Over four decades after the publication of McCarthy’s first novel, the combined popular success of The Road (published in 2006) and the Coens’ No Country brought him and his work into the public eye like never before. The once-infamously reclusive author blushed and whispered through a nationally televised interview with Oprah Winfrey in honor of his Pulitzer-winning post-apocalyptic road novel, and was suddenly available to speak (on occasion) with journalists, artists, and Hollywood agents. When the film world took notice that he could be successfully adapted, the response was quick––the majority of McCarthy-derived projects on the screen would be released within a roughly four-year period ending less than a decade prior to his death. The first of these was The Road, from Australian director Hillcoat and Mindhunter writer Joe Penhall.

Once again backed by the Weinsteins, this adaptation is, ironically, slavishly literal in its rendering of a hallucinogenic novel with intentionally little plot or structure. A cavalcade of star actors––Viggo Mortensen, Charlize Theron, Robert Duvall, Guy Pearce, Michael Kenneth Williams, and a young Kodi Smit-McPhee as Viggo’s son and traveling companion––deliver the novel’s sparse dialogue largely as it appears on the page, and its ravaged hellscape (shot mostly in Pennsylvania) is an impressive showcase of late-00s digital gloom. But Hillcoat, unlike the Coens, is unwilling (or unable) to render the poetic qualities of McCarthy’s prose that set The Road apart from a thousand other works of post-apocalyptic fiction. The author’s impressionistic collapse and protraction of time through (a lack of) structure are met by a film reluctant to hold a shot for more than five seconds. His painstakingly monotonous, methodical descriptions of characters trudging, scrounging, and scanning for danger are adapted to cut hastily through “the boring parts” to sustain action, thereby diminishing the action’s gravity.

The novel’s funereal quietude and calculated sparseness of affect and story become a work with expository flashbacks and voiceover to orient the audience, and a frankly overbearing score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis to declare which scenes are sad, happy, or frightening––as if, say, the image of a knife held to a child’s throat doesn’t speak for itself, or as if without such audience handholding the depiction of this desolate, posthuman world might confuse or upset the poor viewer too much to navigate by themselves. The Road has its defenders, but compared to No Country most agree it exists firmly in the shadow of its source material. Of note: a short based on McCarthy’s Outer Dark, directed by Stephen Imwalle, was also released on the festival circuit in 2009. As of this writing it cannot be found online, and even images from the film seem never to have touched the Internet. John Hillcoat is currently attached to the long-rumored adaptation of Blood Meridian, for which McCarthy had perhaps contributed to a screenplay prior to his death.

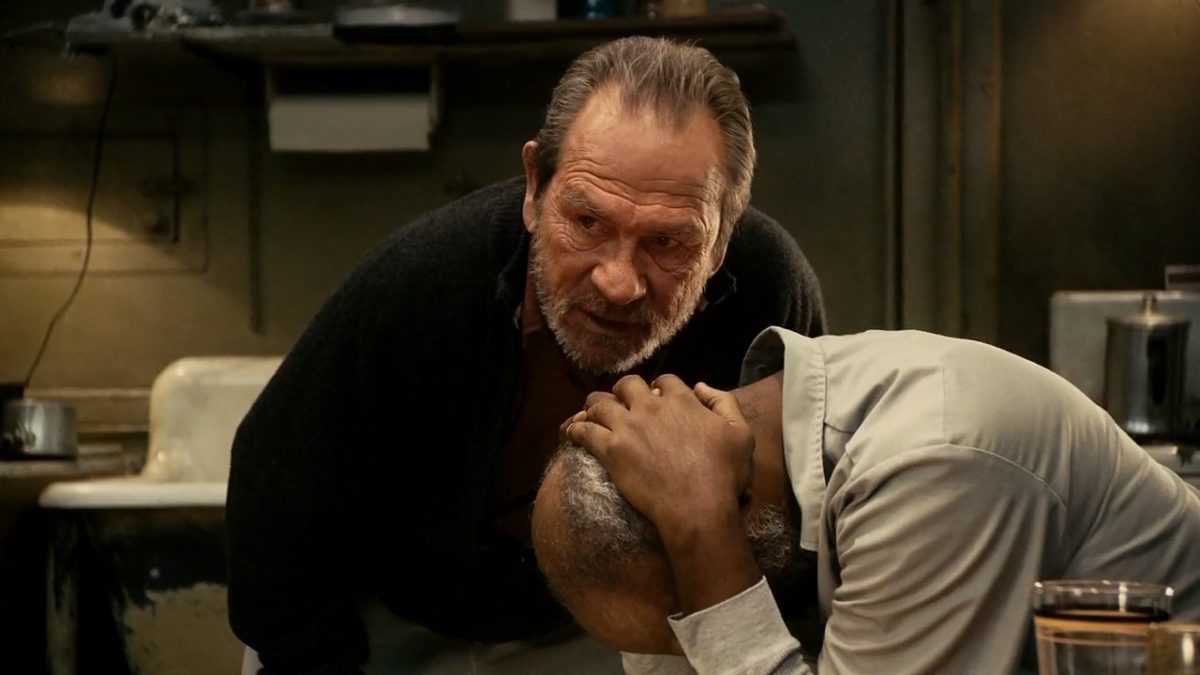

The Sunset Limited (Tommy Lee Jones, 2011)

Quieter but in many ways stronger than the other post-No Country spins, this HBO film’s script was adapted by McCarthy himself from his stage play of the same name. Jones both directs and stars as an academic on the brink of suicide––Western civilization is dead, he declares––opposite Samuel L. Jackson, a gregarious Christian ex-con determined to talk Jones out of the act. Like several of thue writer’s late projects it approaches the realm of pure parable––the characters do not even have names––but in doing so it is also perhaps the nakedest encapsulation of the spiritual and moral concerns that animate his work. Jackson’s character is one of the most fully and proactively moral in all of McCarthy’s fiction, a penitent sinner who now chooses the good because it is good, a selfless knight of faith as superhumanly dedicated to his cause of love and charity in the face of oblivion as Anton Chigurh is to nihilistic malice. In defense of his unconditional love for mankind, he declares: “God would not have appeared in the form of a man if the form were not fit to contain Him.” His optimism is resisted by the scowling, pacing, nebbish Jones, a man whose professed love of intellectual pursuit has soured to hate as he sees the contradictions in everything and everyone around him, who eggs on Jackson to disprove his despair even as he claims he will not listen. Though this heady exchange could easily slip into dour lecturing, McCarthy imbues the two characters with a humor and humanity that complicate their status as pure archetypes: there are ribald jokes, anecdotes about drinking, discussions of the ideal chili preparation, even Jackson ribbing Jones’s squeamishness about the frank realities of race, poverty, and politically incorrect language, all rendered in eloquent prose that the two master actors and Jones’s understated, sensitive direction render fully organic. It’s a heavy, complex chamber drama to challenge the accusations of nihilism often leveled at McCarthy, and an underappreciated gem in both master actors’ resumes.

Child of God (James Franco, 2013)

The undisputed nadir of McCarthy onscreen is Franco’s shoestring-budget adaptation of the 1973 horror novel about an Appalachian hermit whose extreme alienation and animalistic ways turn gradually to atrocity. The novel, like much of McCarthy’s work, uses its beautiful prose and repellent subject matter to tease Hobbesian questions about human consciousness and its relationship to the natural world. Franco, however, seems to have seen in it exclusively a story about a pitiable serial killer, to an extent which may have amused the author himself. The 2013 film is largely a procession of ugly, cheap-looking, amateurishly edited scenes adapted literally and artlessly from the pages of the novel, poorly acted despite E-for-effort contributions from the likes of Scott Haze and Tim Blake Nelson, and generally conveying no sense of place or pace crucial to the novel’s spiral into Deep South darkness. Franco lavishes attention on scenes of sexual violence and necrophilia (all of the titular character’s victims and near-victims are, notably, conventionally attractive young women with a similar body type who bare their breasts for the camera) yet the great mountainous natural milieu equally crucial to the story is practically an afterthought, crammed shapelessly into the backgrounds of shaky iPhone-like cinematography and digitally desaturated to a bright sterile grey. (Hillcoat’s The Road, at least, boasted depth and darkness in that color.) Franco occasionally even puts up the actual words of the novel onscreen, almost like a buffer, to proclaim Child of God’s superficial faithfulness. It’s the most extreme illustration of the quality common in lesser McCarthy adaptations: an eager adherence to the literal plot events of his fiction, oblivious to the poetry and philosophy contained in the words between the dialogue that make it more than just genre patchwork.

The Counselor (Ridley Scott, 2013)

The final McCarthy-derived film completed during his lifetime is also, perhaps, the strangest. His original screenplay, written as a five-week reprieve from the years-long development of his final novels The Passenger and Stella Maris, reads as something of both a frustrated vent and an act of defiance against his critics. Set in the modern day rather than the past, it is a scathing morality tale about beautiful, sexy American bourgeois sophisticates with cell phones and Internet access playing hot potato with Mexican drug money, to predictably grisly consequences. It is conveyed almost entirely in lengthy monologues of the deepest-fried ponderous prose he ever produced, paraphrasing Hegel and Goethe amidst streams of obscenities, slurs, and uncharacteristically graphic sex talk, pontificating on familiar themes of fatalism, choice, and chance within seething diatribes on capitalism, the moral decline of the West, and the oh-so-mercurial nature of women (the latter represented by perhaps the most dead-serious invocation of the Virgin and the Whore in recent memory).

When not knee-deep in verbiage it lays down some of the most outrageously sadistic concoctions in the McCarthyan canon––not just plot devices, but also a literal pocket-decapitation device, the “bolito,” invented by McCarthy as the all-powerful cartels’ assassination weapon of choice––before concluding on a note of absolute darkness, without the slightest hint of redemption or transcendence anywhere to be found. It’s the author’s most deeply embittered work in a body of work not exactly known for its humanitarian warmth, bristling with disgust for its characters and audience alike, politically echoing the fury of Occupy Wall Street but equally predicting Trumpian hysteria over the apocalyptic threat of Latin American cartels on US soil.

Ridley Scott, in his first work completed following the tragic death of his brother Tony in 2012, seems primed to match McCarthy’s bitterness and despair, but the writer’s heightened poetic register proves a bizarre match for the director’s late style. The Counselor is presented through his ultra-crisp digital lens as a sleek, sexy crime thriller: this serves it well in its handful of enervating, ultraviolent setpieces but leaves it in puzzling, sometimes laughable territory as actors on ultra-realistic sets with standard shot-reverse framing struggle to naturalistically deliver dense theatrical dialogue. Once a certain degree of gritty aesthetic realism is achieved in depicting a snuff-film-producing cartel jefe (Ruben Blades again, incidentally) delivering an impromptu lecture on poetry and Heidegger, it becomes a bit difficult to take seriously––especially when it’s presented as the film’s emotional climax. Michael Fassbender, Javier Bardem (again), Penélope Cruz (again), Brad Pitt, and a painfully out-of-her-depth Cameron Diaz try their damndest to sell all this and, for better or worse, to make it sound real––not an easy task when their characters on the page are ciphers and archetypes.

A more holistic realization of McCarthy’s script might have opted for either a Coenesque absurdism to render it as pitch-black comedy, some emotional interiority and sincerity to make it plausible as tragedy, or a surreal, stagey expressionism fully abstracted from its allegedly real-world setting to let the baroque language take on a life of its own. Sir Ridley’s cool, lucid detachment permits none of these, and the result is a queasy contradiction of a product devoid of any discernible feeling but contempt. Some people find the contradiction enthralling: despite failing to win over critics or audiences on release, it retains a devoted cult following drawn to its one-of-a-kind strangeness, molasses-rich language, and uncompromising acidity. Whatever else it is, The Counselor is hardly forgettable. Like many Ridley Scott films The Counselor exists in two versions, a theatrical two-hour cut and a twenty-minutes-longer extended edition featuring more of McCarthy’s monologues. The latter’s pacing is unsurprisingly a bit lumpier, but given that this is hardly playing by conventional cinematic rules to begin with, the even-more-verbose version might be the truer experience.