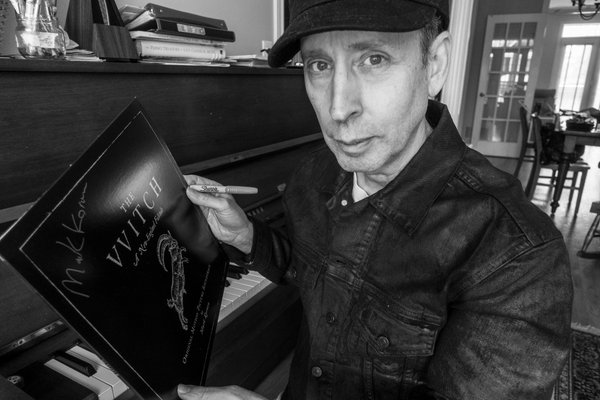

Mark Korven is a Toronto-based, award-winning composer of music for film and television, and has also composed feature film scores for acclaimed directors Deepa Mehta, Patricia Rozema and Vincenzo Natale. His latest work, for Robert Eggers‘ feature The Witch, helped elevate the truly unsettling film. The story follows a family of seven who are pulled apart at the seams by a malevolent force; while there are prolonged moments of downtime, it is still non-stop tension. The film is a “folk-tale” and if there’s anything to be learned, it is to honor your Mother and Father, don’t make a pact with Black Phillip (or any goat for that matter), and never play peek-a-boo with an infant in a New England field.

Sometimes, a film and its music are so symbiotic it’s impossible to separate one from the other. For instance, were you to only listen to the music from Timecrimes, you might not get the same feeling away from the picture. As such, the music to The Witch is like half of an eerie peanut butter and jelly sandwich – they can be enjoyed apart, but for maximum effect, they really belong together. We had the pleasure of chatting with the composer about his experiences creating the score, and one can check out the full conversation below.

The Film Stage: The Witch has been out for a bit now, and it is picking up fans wherever it goes. How have you viewed the reception to both the film and your music?

Mark Korven: The response really took me off guard. I initially thought that the film was going to have a really rough time – being the dialogue was spoken in Jacobean English – and I really didn’t consider it in the vein of a modern horror film, or something that would cater to typical hard fans. So I was surprised when it did so well at Sundance and all the good things that are following.

It is really good in that it makes you feel really bad. I have no shame in admitting that the film, and your score, gave a 36-year-old man nightmares. I hope you’re happy.

[Laughs] Just doing my job!

The score is great because it’s expected and yet not expected. It’s got the screechy/scratchy notes that put you on edge, but there are a lot of instruments that people don’t associate or anticipate being essential to this soundtrack. That and the choir just took things to another level. Will you break down your process of selecting instruments and creating this palette? Also, what discussions did you have early on with director Robert Eggers?

I should preface this by saying that, musically speaking, I came into this with Robert knowing very, very well what kind of score he wanted. He’s very much a hands-on director, and that goes right from what kinds of buttons are on everyone’s shirts, the art direction, the screenplay, the cinematography, direction, and everything else.

I should preface this by saying that, musically speaking, I came into this with Robert knowing very, very well what kind of score he wanted. He’s very much a hands-on director, and that goes right from what kinds of buttons are on everyone’s shirts, the art direction, the screenplay, the cinematography, direction, and everything else.

Rob was very much in control, and that applied to the music as well, and there were some rules he set down in our very first meeting mainly that he didn’t want any electronics. It all had to be instruments from the earth, made by people, because he wanted a organic nature to the sound. He didn’t want the music to be traditional, in melody or harmony, or anything that brought it back to the 1630s. But he wanted the sound of the instruments to be old and archaic.

What I brought into the picture was an instrument called the Swedish Nyckelharpa, and it dates back to about 1350. It’s essentially a push button violin of the 1400s. I heard someone say it was a cross between the typewriter and your grandpa’s old fiddle, because the keys click and clack. It has a organic quality to it, and as soon as Rob heard it he said, “Yes! That has to be the instrument that is going to carry the score.”

So that’s what we started with, and is the basis of the score, but the choir, that was something that I convinced him to add. I told him, “We have to have some vocals in here, and I know the perfect choir – The Element Choir out of Toronto – and they specialize in improvisation.” So we didn’t write any notes for them at all. It was all completely improvised with a lot of guidance from us.

Many times you hear a choir, and it’s along the same notes and harmonies the instruments play. But the choral runs in The Witch were directionless yet captivating.

They got to feel their way through the picture for sure, but we gave them a lot of guidance. And so, one time I told them, “Okay, for 10 seconds I want you to sing one note, and then you three come in with a really strange note, and then everyone starts whooping for 5 seconds and then build to a great chaotic crescendo…then when I drop my handkerchief, everyone stop.” That was about as much as we gave them. [Laughs]

Does it ever help your process to not only establish what a film is, but maybe with a film isn’t? I mean, this film is not really a horror story — it’s more of a familial drama. There are less jump-scares and horror tropes because it is terror on a human scale.

You’re absolutely right about that. I really view this as less of a traditional horror film and more of a family drama, because that really is the heart of the film. You watch this family fall apart, and there are these great performances all around that. Regarding the idea of freedom and establishing what a film isn’t, I always like to quote Stravinsky who said that there is great freedom within structure.

Sometimes when you lay down the creative walls and you decide what you’re not going to do, that frees you up in a way, because when you have total freedom that can be a prison in itself. It’s almost debilitating because you don’t really know what to do. So it worked out very well, and made the score more creative to have Rob lay down some very good rules to the score.

Going into a film like this, you have to know that this would not end well for anyone. From pretty much the first frame, we are thrust into the misery right along with the characters. There were scenes where the music seemed intentionally held back. You have these unsettling cues, but then you’d have a lot of downtime where it was eerie just because it was quiet. What discussions did you have with Rob about when to place music and choir, and when not to?

Most of that came from Rob, because he had a very clear idea of what he wanted. We decided that the choir would be mostly about The Witch, so we would never hear it in anything that involved the family unless she was present which would justify it being in the scene.

What specifically did you look for, in the film, to use for inspiration? I noticed, in one early scene, the music seems to pick up on the sequence when The Witch was performing a ritual. She was grinding something, and by using that sound source as a reference, it seemed like the music enhanced what was happening.

That cue was mostly driven by the Nyckelharpa, and we worked with it for quite a while. Rob would nod his head say, “Yes, that’s working good.” Then at the last minute, he thought we needed to push it in a slightly different direction and wanted to use another element to lift it just a little bit more. So we brought in this instrument from Finland called the Jouhikko. It was played by a good friend of mine named Ben Grossman. He plays the Hurdy Gurdy and many other instruments. The Jouhikko is an instrument with three heavy gut strings and a very primitive bow, and it can give a really scratchy and primitive sound which seemed perfect for this old witch.

A director sees the film numerous times before getting their “final cut” and can end up making many edits along the way. How many times did you revise your music or play around with certain elements and cues before you were happy with it?

It was a long process, and a very unusual one as well. Typically, when I do a film score, I do my sketches. I might send those sketches to the director or show them when he comes by my studio. He would give some feedback, I’d take some notes and then work on it, and when he comes back a week or two later to revisit – we’d do this a few times – we’d put that music into the mix. This, however, was a very unusual process in that Rob kind of moved into my house for about a week, because we’d work all day, have dinner, then work into the evening. He’s very hands-on and persistent in his attention to detail, just as he was for every other element of the film.

Normally that would drive me crazy, but it was different with Rob because, for one, he’s a super nice guy and we’ve gotten to be really good friends. Number two, I could tell, from the very first minute I met him, he was a very talented and visionary director. It felt like I was meeting a young Ingmar Bergman or something like that, and I really wanted to be part of what he was doing. So I parked my ego at the door, and I said, “Whatever I can do to help you achieve your vision, I’m here to help.”

Rob wanted a very dissonant score that never let up. So part of my job when I started was trying to figure out a way to make that work so that the audience didn’t start to yawn! If you’re starting from +11 on the dissonance scale, where do you go from there? I was like, “How do you get louder than 11?”[Laughs] So you find other ways of doing that, and one of the ways we did that was through lots of space in the score, as you pointed out before, and we played with the density of the instrumentation in the points when we really poured on the score as well as using instruments we had never heard before.

Do you listen to the music afterwards?

I never listen to my own music, and I have no desire to. [Laughs] No reflection on my abilities, but it just never comes up.

In the credits, I see you play the “waterphone.” Having an understanding of certain instruments is necessary because it helps you compose. But how do you write music for instruments you don’t play?

I’ve played the Waterphone for quite a while, and it is, at the heart of it, a very, very experimental instrument. Whether or not you’re good at it, you are still very inclined to play and experiment, because it is not a virtuosic instrument. Other instruments like the Nyckelharpa and the Hurdy Gurdy are virtuosic, so they don’t lean towards experimentation.

But as far as having no knowledge of an instrument and trying to write for it, it comes down to two things. First off, it’s always a good idea to have some awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of an instrument so you don’t embarrass yourself to the musician. [Laughs] You don’t want to bring a cello player in the studio and have them play something lower than a low C, so as a composer you have to have a working knowledge of every instrument that you work with. That comes with the territory. Now the other half of that is when you are writing a very experimental score, it’s almost better that you don’t know how to play it because you’re looking for those happy accidents.

It’s tough to know the impetus of the witches – it just seems like random chaos – and the success is due to us never really knowing what they’re all about. The film ends, and it sticks with you like chewing gum… but I don’t know who I would recommend this to.

I know, I know! After you’ve seen it, the film can really sit on you like a weight. But that was Rob’s intention, he said he wanted the film to feel like a 90-minute nightmare, and I think he got that because this was a really, really heavy film. He aimed to do something really different, and he’s influenced by many different people, none of which are contemporary horror directors. He’s much more fond of European directors, so if you’re feeling that dread, and a nightmare quality, that’s what Rob was looking for.

Visuals and the score in The Witch can’t prepare you for that ending. It is, in my mind, on par with scenes like the elevators of blood in The Shining, and Jaws’ head exploding. That scene, when the witches have their seance, and then rise up into the air, will be solidified in my head for probably the rest of my life. Where did your music for that come from?

Well, the inspiration came from a piece that Rob brought me to use as a reference. I don’t remember what it was, because I tried not to get too married to it or let it influence me too much during the writing process. But it was a tribal piece with very dissonant sounds. We used it as a jumping-off point. My suggestion of making it an improv choir piece worked quite well. The session was a lot of fun because at a certain point, I even got Rob out there conducting (waving his hands around!) which he really loved doing. I think we freaked the recording engineer out a little with that session. We were going to some dark places! [Laughs]

For an audience member to hear it and then be blown away by it, once is probably enough. But you guys had to do this for weeks, so what efforts did you take to bring the levity up after these dour sessions?

[Laughs] To people that don’t know Rob, they might think that he’s a very dark and serious individual. I suppose he is on a certain level, but he’s also a lot of fun. He’s got a fantastic sense of humor, and he really doesn’t take himself too seriously at all. So he’s very fun to be around, and not what people expect him to be.

Whether it’s Cube, The Witch, or a number of documentaries, you’ve got a very distinct sound. So what’s next? How do you branch off from this? Or do you, more or less, plan to stay in this zone?

I’ve been getting a lot of offers for more conventional horror films, mostly slashers, which I really don’t have much desire to do. I’d prefer to be involved in things that are much stronger as far as storytelling. In the horror vein, I like movies like Let the Right One In or Rosemary’s Baby which have really compelling stories. I’m not really into doing horror for horror sake.

I just want to do really good films. I know Rob is getting lots of things lined up, so I’m hoping he and I get to work together again because I think we make a really good team.

The Witch in in theaters now and arrives on Blu-ray on May 17th. To hear the full score, listen here or pick it up on vinyl, and for more of his music, head to Mark’s official website at MarkKorven.com.