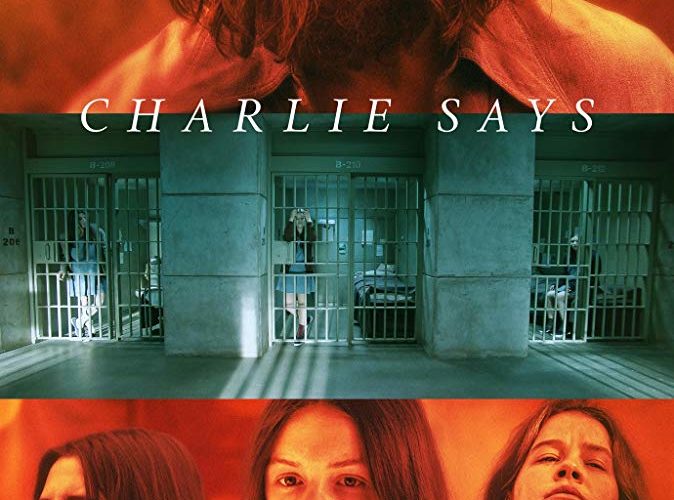

Certain events enter our collective consciousness and change its landscape forever. We watch news footage and listen to interviews. We read firsthand accounts. What we miss is the day to day unfolding of the plot, and as it turns out, the devil is in the details. Mary Harron’s latest film, Charlie Says, provides a unique look at the Manson family. Its emphasis lies not with Manson but his girls, their relationships, activities, and specifically, the incarceration of Susan Atkins, (Marianne Rendon) Patricia Krewinkle, (Sosie Bacon) and Leslie Van Houten (Hannah Murray). While never offering excuses for the actions of its principal subjects, it illustrates how the perfect storm of insecurities, a cultural movement, and a misguided need to be loved led to one of the most infamous crimes of the twentieth century.

Harron grasps the subject matter with the same elegance she brought to American Psycho. A sense of foreboding pervades each scene as the camera lingers on faces, colorful shawls, and stringy, dusty hair. Under Krenwinkle’s earth mother tutelage, new recruit Van Houten experiences warm inclusion but stumbles over the ranch’s cheerful misogyny. Family women are not allowed to hold money and only fix their dinner plates once the men have begun eating. She exposes the contraction in Manson being vegetarian yet demanding a suit made of deer skin. Had Manson accomplished his goals in the music scene he may have ditched the Family completely. Instead, he sinks deeper into a frustrated mania that fed upon and inspired the rampant insecurities of the girls and Tex Watson (Chace Crawford). We cringe as Van Houten declines an offer from a motorcyclist to leave the ranch, placing her deeper inside a family that thought with one mind. The film is at its strongest when presenting female pushback to Manson, played by Matt Smith in a riveting performance. One blonde visitor expresses disdain at Manson’s behavior and condescension. She tells him off and for that moment, we see Van Houten quiver in indecision, slapped by reality. In these moments of contradiction we are enthralled not by Manson’s circular verbiage but by women who do think for themselves, who are comfortable with personal agency, whose need to be loved never outweighs their common sense.

While the girls are most engaged during garbage picking or singing songs, their eyes retain in “B.C,” (Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkle’s glib nickname for “Before Crimes,”) the dullness they possess during family dinners or post-murders. Whether characters are free on the ranch or locked inside prison, Crille Forsberg’s cinematography creates sensorial cues through golden California tones or flat blue-grays. Teacher and rehabilitator Karlene Faith (Merritt Wever, a welcome addition to any cast) is tasked with handling the incarcerated Manson girls and is struck by their insistence on a diet of Charlie-fed nonsense. She continually asks each, “But what do you think,” and as time goes on, we watch them become unsettled by Karlene’s pokes into Manson’s unhinged commentary. Faith also served as a consultant for the film, her experiences connecting the dots in ways that news accounts and interviews could never do.

The often-repeated phrase “Charlie says” serves as the film’s emotional center. It isn’t what Manson did, it’s the way his ideas wormed inside the brains most eager to accept and/or misinterpret them. The ensemble cast is terrific, inciting empathy but also frustration and shock at their willingness to murder and deny basic truths. Onscreen violence is mercifully brief, but more disturbing is the look settling onto Van Houten’s face as she participates, staring at us instead of her victim. In Charlie Says, Mary Harron presents the in-between life, the seemingly banal details that orchestrated this perfect storm of destruction. By including diverse female reactions to Manson, we understand more about what happened and how, had circumstances been even slightly altered, it might never have occurred in the first place.

Charlie Says opens on Friday, May 10.