If Carl Franklin may not have many films in his oeuvre, what’s present has certainly made its mark. His 1992 neo-noir One False Move was originally set by the studio to go straight-to-video, only to be rescued by critics like Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, who caught it in advance and gave massive praise to its complex characters, rich world-building, and no-nonsense approach to the violence that American culture is steeped in. The film would go on to be Siskel’s number one of the year and receive the full theatrical release it deserved.

With a bump from One False Move’s critical cache, Franklin set about for his incredibly ambitious follow-up: Devil in a Blue Dress, an adaptation of the acclaimed Walter Mosley novel, with Denzel Washington to star in the role of Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins. In Los Angeles during the summer of 1948, two weeks behind on his mortgage and having just lost his job, Easy is enlisted as a private eye by the questionable DeWitt Albright (Tom Sizemore). His assignment? Investigating the disappearance of Daphne Monet (Jennifer Beals), mistress to a hotshot mayoral candidate. Of course, in this world, things can’t ever be so simple.

Having roots in the area, and an interest in our past that had him pursuing a history major in college before he switched to theater arts, Franklin immerses us in this noir tapestry as Easy plunges deeper and deeper, eventually calling in the help of his dangerous friend Mouse (an explosive, scene-stealing Don Cheadle). The tension and danger only pushes higher and higher for Easy, but the temptation of the almighty dollar, and the need to uncover the truth, keeps him on the hunt.

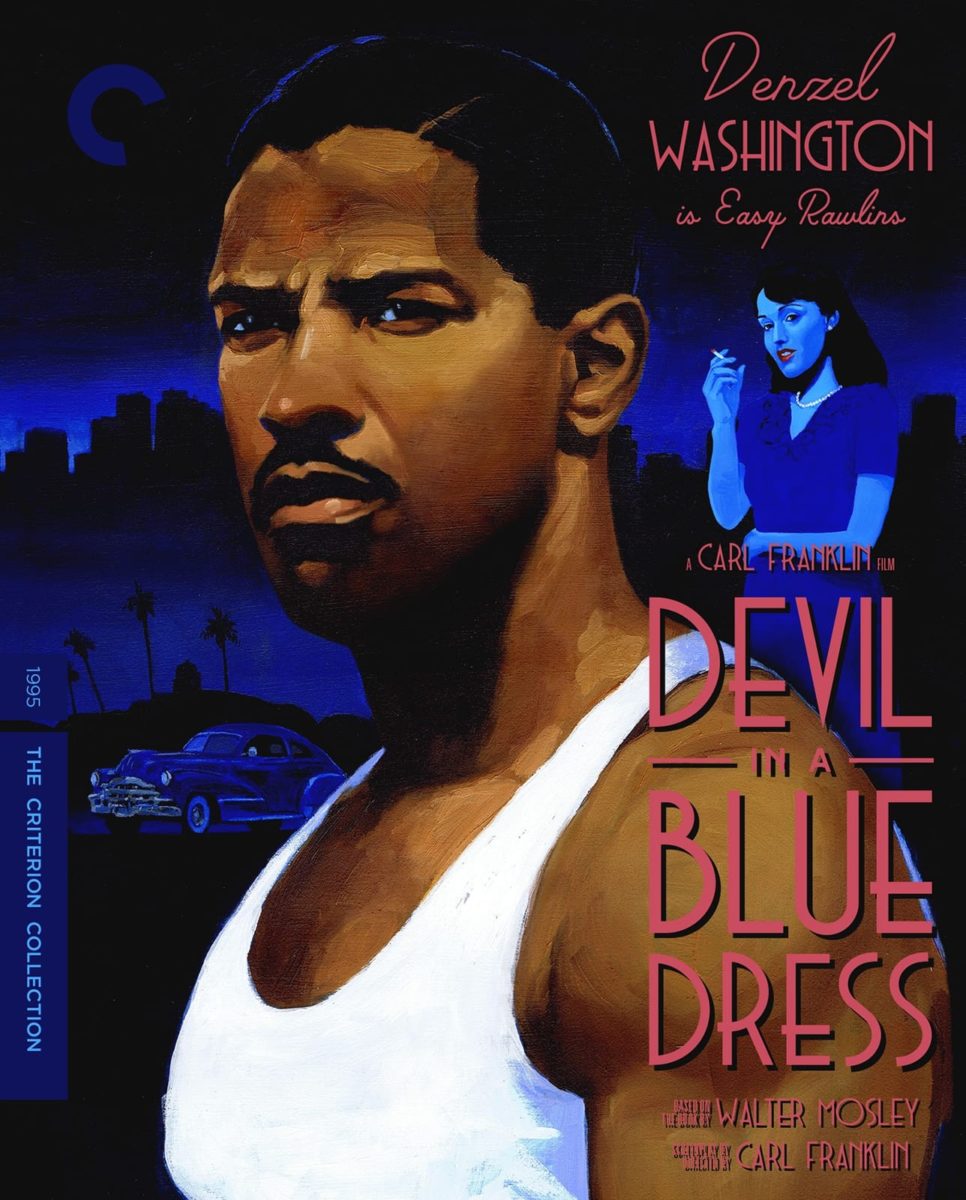

Devil in a Blue Dress didn’t set the world ablaze upon its release in 1995, but in the years since it has gained far greater appreciation, playing repertory screenings amongst some of the finest of the genre. That respect has now garnered it a sterling new 4K Blu-ray release from the Criterion Collection, jam-packed with extras including a new conversation between Franklin and Don Cheadle, a commentary track from the director, and a 2018 Q&A conducted by film historian Eddie Muller at the Noir City Film Festival in Chicago.

To celebrate the new release, I spoke with Franklin about the film’s enduring legacy, its themes on money and race, and the ways it both embraced and subverted noir conventions.

The Film Stage: I was reading this interview you did around the release of One True Thing where you described having a difficult emotional experience after Devil in a Blue Dress, partly attributed to ineffective marketing resulting in the film not getting the audience it deserved. How does it feel now, seeing the increased appreciation the film has received over the last couple decades?

Carl Franklin: Hey, it’s great, man. It’s the one thing that I have wanted with this film––is that it still seems to have legs. People reference it as one of the movies that they remember, and that’s a great honor to me. It’s a film that has somehow worked its way into the American iconography, or whatever you want to call it—that it’s viewed as an American standard or something.

I was thinking of the phrase “modern classic,” myself.

Yeah, yeah. That feels great, man. I couldn’t ask for more.

I know you’ve revisited the film plenty of times over the years, going to repertory screenings and everything, but when you’re taking on the oversight process for the 4K release and looking back on it all, how do your thoughts and feelings on it now compare to when you were making the film?

You know, now that I’m removed from it, I can kind of see it more as an audience member. At the time, when you do it, you’ve still got your hands in there. You’re still not that far removed from the mechanism, so it’s hard for you to sit back and receive the film in that same way. It’s refreshing to be able to do that, and to actually find myself really laughing at some of the things we did at the time. Having fun with the film. I can now go into the world and absorb it, enjoy my own suspension of disbelief, as opposed to remembering, for instance, the scene where Daphne Monet is out at the ranch with Albright and just remembering how cold it was the night we shot it. [Laughs] Those associations fade away and you can just think about the film—so I’m enjoying it.

Getting into the film itself, Easy is such an interesting character in the way that he’s sort of the anti-noir hero. He’s essentially a detective by circumstance. He lost his job, he’s behind on his mortgage, and he’s just doing it for the money. Tell me about taking that unique entry point for the character into this world.

That was part of what was interesting to me. In the film noir genre, a lot of guys out of Eastern Europe came over to the United States and expected it to be this upstanding, democratic answer to the fascism that was sweeping Europe. Then they got here and saw that the corruption here was just more civil, more below the surface. The traditional film noir character is a guy who’s very cynical, he’s already got this cynical view of the world, and oftentimes his journey will be to have a character that will somehow present the glimmer of opportunity for him to see hope. You take Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon and the Brigid O’Shaughnessy character, who for a second, he feels he could actually fall in love with her. The same thing with Chinatown, where the J.J. Gittes character starts to fall in love with Evelyn Mulwray, only to realize he’s fallen into the trap that he was afraid of from the very beginning.

Easy’s different from that. Easy’s a guy who actually had hope, he had more optimism about life, and he learns some lessons over the course of the film. He believes in the American dream, and then he finds out that in the real American dream there are mechanisms at work, cogs that exist in this subterranean world of leg breakers and backroom dealers. He gets acquainted with the real American dream and he emerges at the end a little more cynical, but still fairly optimistic. So yeah: he is kind of the anti-film-noir hero in some ways.

The film has this great sort of bookend where, early on, there’s the scene with Easy, Joppy, and Albright where it’s mentioned that it’s rare for Easy to be a Black man at this time, in this area, who owns his own home. Then at the end there’s that gorgeous line, “I sat with my friend, on my porch, at my house.” What does that idea of Easy being a Black man owning his own home mean for him?

Well, you know, I could relate to that because I was part of that whole migration. My family was part of that migration from Texas to California. My brother is three years older than I am, and he and I were the only two in our family who were born in California. Everyone else was from Texas, so they were part of that migration, and when I was born I spent the first eight years of my life in the projects, those wartime project homes. Well, they weren’t homes—they were apartments. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen those things before, but that’s where I spent the first eight years of my life, so the prospect of owning a home for a Black person was a very novel thing. There weren’t a lot of people who did.

I had family that had a construction company, and they started to buy houses while we were on the poorer side of the family. But that other side, with my half-brothers and sisters, they were doing pretty well. I always aspired to emulate them in some ways. So I have firsthand knowledge of all of that. It was an important thing for a lot of folks, and it wasn’t just Black people either. There were a lot of whites who came from the south who had the same circumstances. The idea of buying a home and owning property was all part of that post-World War II boom, where the economy was really profiting from all of the industrialization, and all the jobs that were created by the war really boosted the economy.

Money is certainly a key element of the film. I was struck this time around watching how these powerful men like Albright, Terrell, and Carter would just throw hundreds of dollars at Easy like it’s nothing so they could get him under their hook. What does money’s part here say about the social dynamics and conditions of these characters?

That’s the thing, and what it says about the characters, specifically about Easy, is really important. What happens is that the more money he gets, the more compromised he’s becoming. The more he’s willing to become compromised. That’s kind of a statement about society itself: that if you are willing to get your hands dirty, you can make a lot of money in this country. It’s that whole capitalist market culture that we have. If you really want to just make money and you don’t want to check yourself in terms of what your moral compass is telling you, what your sense of humanity demands, then you can do quite well. He takes that dollar, he makes that pact with the devil when he’s with Albright, and he just sinks lower and lower, but he’s getting more and more money, and submitting himself to more risk. That’s America.

Daphne is similar to Easy, in the sense that she fits the mold of the femme fatale, but she’s unique in several ways. She’s this enigma we don’t see for a large chunk of the film, and then that first scene with her and Easy is so electric, so charged. Walk me through the construction of that first scene with her, how you wanted us to be introduced to that character.

Well, in the book they actually do have sex, and I felt that would betray the character, because in some ways she’s a little bit confused. So yeah: in the way that Easy is that anti-noir hero, she is sort of the anti-femme fatale. To go back to The Maltese Falcon and Brigid O’Shaughnessy, that’s a character who was using her feelings to manipulate people. Daphne is basically trying to arrive at a point where she can fully express her feelings. She’s in love. Her motivation is to be able to have a real relationship with someone across racial barriers. She’s believing that somehow the love itself can push certain problems aside to break convention.

She’s quite idealistic, whereas Brigid O’Shaughnessy is not. And because of Daphne’s commitment to Carter, I couldn’t really let her and Easy have sex. Because then it’s like: how is she going to sleep with Easy when she’s supposedly in love with this other guy? That would violate her motivation. So we wanted to suggest some of that heat that is in the book, but we couldn’t actually go through with it. That’s really the most manipulative that she is, is in that scene where she does basically come onto him a little bit. And then she’s willing to do it again later when she comes and finds out he has the pictures. Ultimately, though, she’s doing that reluctantly.

It is a great bait-and-switch, because yeah: she’s introduced as somewhat of a conventional femme fatale, and slowly you peel back those layers to allow us to understand how we’ve misconceived her.

Right, yeah. It’s similar in some ways to Chinatown. It’s not quite the same, because Evelyn Mulwray is more in control of her environment than Daphne is. Evelyn’s still a victim—she’s a rape victim, of course—while Daphne is more of a social victim.

Another character that’s not introduced until quite a way into the picture is Mouse, which always surprises me because Don Cheadle’s performance is so stunning that my memory always tricks me into thinking he’s in the whole thing. He’s there in Easy’s mind for a lot of it, sort of like this specter hanging over him, and then when he’s introduced it’s like a handful of dynamite. He just changes the temperature of the room whenever he’s in it. I heard that working with Don Cheadle and seeing what he was doing in his performance altered the interpretation of the character. Could you elaborate on that?

Initially, the character of Mouse was pretty dark––he was more dark than he was funny. There was a hint of humor to him, but he was a pretty dark character. Don, on the other hand, there’s a certain lightness to Don. That’s because he’s incredibly intelligent. He’s a guy who has a certain kind of energy that thrusts itself up rather than down. He’s someone in whom I saw the opportunity to play some really dark comedic moments. Don’s a really funny guy, anyway, because he’s got that intelligence to him so he’s got a very good, very smart sense of humor. He had this interpretation of some of the things that were written that I think he made a lot funnier and more fun.

Don’s a fun guy, and there is a certain lightness to him, but there is a certain something about him when he’s playing bad that is very interesting. I really liked him in Colors, when he played Rocket, or when he played Miles in Miles Ahead, and I still feel that Devil in a Blue Dress is probably his best performance. He’s very convincing as these bad guys, but at the same time he’s very charming and he’s very smart, so when that combination of things comes together it makes Mouse someone who is irresistible in a lot of ways. I was almost concerned about him being so charming. [Laughs]

In working with your actors, you’ve said that the main thing you want to do is eliminate fear, that thing holding them back because they don’t want to make a mistake. What does eliminating that element allow you to draw out of an actor?

I think that the biggest obstacle an actor has is fear—especially when you’re in front of a camera, this thing that is inanimate. It’s not like when you’re on stage. Being in front of the camera doesn’t give you that same give-and-take you get on stage. So when you have that thing looking in your face, for one, and then two, you’ve got a crew of anywhere between 40 and 50 people watching you at the same time—and potentially millions of people who will eventually see it—that changes things.

Especially because you’re trying to do things that people do in everyday life, and you’re trying to be convincing at pretending to do those things. You open yourself up to criticism, where people can watch you and say “God, I’d never fight a guy like that,” or “I’d never make love like that.” All of that kind of stuff, which I don’t know how conscious people are of, but you carry that fear with you. It’s the same as anytime you have to stand up and deliver a speech in front of people—there’s a certain amount of nervousness that comes with that.

For me, what’s important is to arm the players with as much information as possible, and also to make them realize that whatever they do is fine. I trust who they are, and we may do it again. It may not be the best interpretation of the piece, or the best interpretation at the time, or the fullest version of it, but there is no such thing as a mistake. I want them to understand that they’re free—we’re all free to play around here. They’re armed with as much subtext as possible so they know who they are, where they’ve been, where they’re going, where they want to go when they enter a scene so they have tangible things to hang onto, and then we work our way through it. I think the actors appreciate that because that’s the foundation they want, and then we can participate in this invisible world with that.

You’ve talked about how you’ll storyboard action sequences and kind of plan out the general direction of scenes, but you leave open a lot of room for spontaneity and discovery. Is there any scene, or even just a moment, in Devil in a Blue Dress that you could point to as an example of something that was found in the moment?

There were certain things that Don brought, like where he raises his left hand as opposed to his right hand with Easy when he first comes in, and says “I’m gonna let you run the show.” Some of that back-and-forth between them were things that just happened. Originally in the script, and in the book, Mouse was supposed to pistol-whip Frank Green when he first comes in and Frank is fighting Easy. I just felt like that wasn’t something this guy would do. He would be cleaner; he would do something that would be a lot more serious. I thought about it at the time and I said, “Why don’t we try this?” We’ll have him put the big gun away and take out the little gun instead, and that was something we just did on the fly. I remember, in fact, my cinematographer [Tak Fujimoto] was concerned at the time that I was compromising the character and he thought no one was going to like this guy, but I thought it’ll be all right. [Laughs]

The special edition 4K UHD and Blu-ray of Devil in a Blue Dress are available now from The Criterion Collection.