Pablo Larraín is not finished wrestling with his nation’s psyche. His first three films, Tony Manero, Post Mortem, and No, formed a loose triptych that confronted the trauma of the Augusto Pinochet years from different angles. His fourth, The Club, was a blistering attack against the contemporary institution of the Catholic Church in Chile, which accused it of deep-seated corruption and of collusion with the Pinochet regime. With Neruda he returns to the past, back to 1948, the year the eminent poet and Communist senator Pablo Neruda (Luis Gnecco) went into hiding after the Chilean president outlawed Communism in the country.

As radical a reinvention of the biopic as Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There, Neruda is Larraín’s most conceptual and also his most demanding film yet. Like Haynes, Larraín attempts to create a hybrid between his subject’s art and biography, and, like Haynes’ film, Larraín’s is generally more fascinating than it is enjoyable. A crucial disadvantage of Neruda that will make it even more difficult for most is that few non-Chilean viewers are likely to be familiar enough with Neruda’s life and work to fully appreciate Larraín’s portrait of this important artist and historical figure.

This is evident from the first scene, which dives the viewer straight into a heated discussion between Neruda and his fellow senators. The camera rapidly flows through the room and swirls around the speakers, the brisk editing creating a strong sense of urgency as the men dispute the current political situation without preamble or exposition. Those unacquainted with this chapter of Chilean history will be immediately disoriented, though what does transpire is that Neruda is a staunch Communist and that the U.S. is pressuring the Chilean president to join their side of the Cold War, putting Neruda and his cause in peril.

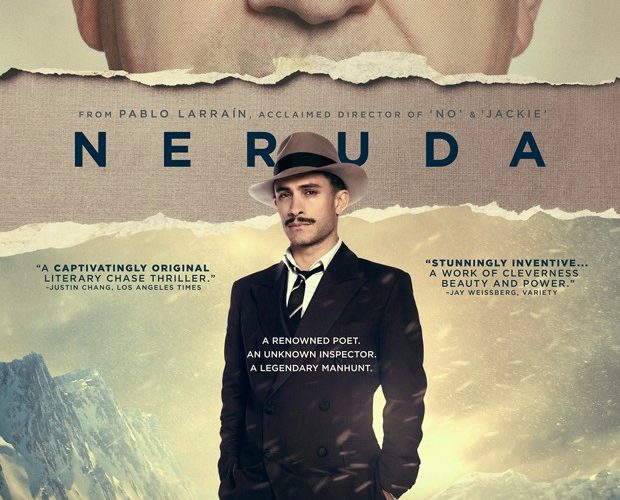

Soon thereafter, Neruda goes on the lam and a country-wide search for him ensues, led by investigator Oscar Peluchonneau (Gael García Bernal). The hunt for Neruda turns personal, becoming an odd type of cat-and-mouse game, with Peluchonneau always just a few steps behind Neruda, who enjoys taunting him by leaving clues for him to follow. It never feels realistic, though, and the film generates little suspense about the possibility of Neruda being captured.

This eventually reveals itself to be intentional, as Peluchonneau is not a real figure — though, according to Wikipedia, there was a chief of police with that name but he came into office four years later. Larraín came up with him as a character that Neruda himself may have invented. In a meta-development, Peluchonneau gradually becomes aware of his fictional status and has a full-blown existential crisis. It’s a fun, very literary contrivance, but how it offers insight into the historical events depicted in the film isn’t apparent.

Neruda is more successful visually. On every level, it is absolutely ravishing. In the early sections, the film is set in a series of gorgeous interiors and it’s a delight to watch the impeccably dressed characters navigate sumptuous locales such as the presidential palace and the senate, or to follow Neruda into his cherished brothels where he partakes in numerous intoxicated and extravagant orgies. Later, as Neruda’s flight brings him to faraway corners of the country, Chile’s nature is put on spectacular display. The climax, which takes place on the snowy summits of the Andes, is nothing short of breathtaking.

The photography by the gifted DP Sergio Armstrong, who shot every one of Larraín’s features, is coated with a smoky veneer that lends the images further historicity, while the conspicuous, impressionistic lighting imbues the narrative with a lyrical feel. Together with a creative use of editing, which regularly violates spatial and temporal continuity — often locating the same conversation in several different settings simultaneously — Larraín invents a new form of cinematic poetry by channeling the creativity of his subject. Neruda is a head-scratcher, but its sensual pleasures are undeniable.

Neruda premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released on December 16. See our coverage below.