When a filmmaker decides to tackle a story like Bombshell—which is set in the right-wing environs of Fox News—it helps to have a director who grew up in a conservative household, someone who can speak to the conservative mind, and understands the incendiary network’s appeal to that mind. It also helps to have someone who can humanize the sensitive and sadly universal experiences of its three leads without having to lean on political finger-wagging. Although director Jay Roach admits he feels like the outcast in his family given his left-leaning ideologies, he also acknowledges that these differences allowed him to develop a distinguished sense of self, and embrace his individual political identity. And though the film has been met with criticism for seemingly letting its propaganda-sympathizing protagonists off the hook, as well as the skepticism of having a male director be in charge of communicating this material, Roach’s upbringing allowed him to approach this film with the empathy, respect, and open-mindedness it deserved.

Here, the director—who’s pivoted in recent years from broad comedies like Austin Powers and Meet the Parents to more politically-driven fare—talks to The Film Stage about these justified concerns, how he addressed them, the ways in which Bombshell opened his eyes to a world of normalized indignities and complicities, and how even the most woke or sensitive among us can still learn a thing or two by just listening.

This interview has been slightly edited and condensed for clarity.

The Film Stage: Bombshell’s implicitly feminist ethos makes it particularly vulnerable to scrutiny in the hands of a male director. Can you talk a little bit about why you decided to helm this project, and what gave you the confidence to tackle this subject matter? I know that as executive producer, Charlize [Theron] reached out to you, but what was the collaborative process like?

Jay Roach: Well, I never would’ve done it without knowing that she and our other female producers, and our incredible female cast, were going to be a part of it. If they hadn’t agreed to make it a full, complete collaboration, I would’ve never felt confident enough to come on board. One thing I feel strongly about is that men have to try and contribute one way or another. We have to speak up, we have to speak to each other—or at least, we should want to, and I very much want to be part of the solution. So it was very much a, “How can I help?” type of situation. These are issues I care very much about, and obviously I can’t begin to understand completely what these experiences are like, but at least I care enough to try and help get the story out, to devote years to it, and to work with incredible collaborators in order to bring an empathy for these women going through horrible situations.

Speaking of empathy, the film is an exercise in empathy for the political left, as well as for men, and male workplace bosses in particular. It’s interesting that you talk about female collaboration, because you said in a previous interview that even as a sensitive man, you weren’t really aware of the internalized shame, disgust, and sense of violation often felt. What were the most valuable and previously unconsidered perspectives or insights that you gleaned from these collaborations?

We collaborated with some of the actual women who were the earliest of Ailes’ accusers to come forward, and we portray their experiences. Some of these women spoke to us off the record, and many of them were bound by NDAs, but a couple did come forward. For example, we had the chance to talk to Ruby Bhatia at length, and she told us the kinds of thoughts that were running through her head when her boss hit on her. We show this through her character’s internal monologue, and that to me was a great example of where just listening—you know, one of the most eye-opening things as a man was being introduced to the idea of how it feels when a woman realizes a guy is hitting on her during what she thinks is going to be a standard professional meeting, and now discovers that he’s pressuring her into having sex. After politely rebuffing him, she realizes that she now has to placate his ego even though he’s being the abusive jerk, and she has to figure out how to talk her way out of this situation so that her career can survive even though she gets the strong feeling that it won’t. In fact, despite the real-life Ruby—she was a great reporter who often went into battle-zones in the Middle East—being a rising star at the time, she gets fired six months into a three-year contract and doesn’t get the chance to work in broadcast ever again. I just don’t think men have any idea of the risks women are forced to take in those situations, and how they have to think so quickly on their feet just to survive from a career standpoint. One has to appreciate the gumption it takes to speak up to support Gretchen years later and break her NDA, even though that meant taking on smear campaigns and personal attacks. These realizations have been life-changing for me, and I hope men try to connect on that empathetic level.

That monologue is in fact frustratingly and depressingly all too familiar for many women, and it was also part and parcel with the film’s ability to convey the nearly impossible situation women who want to be recognized for their professional merits face when their ambitions are used against them, and how standing up for yourself can very well mean throwing away your entire life’s work—the sheer helplessness and moral outrage of it all. Can you talk a little bit about how you capture the tension of that kind of culture which pits ambitious women against each other?

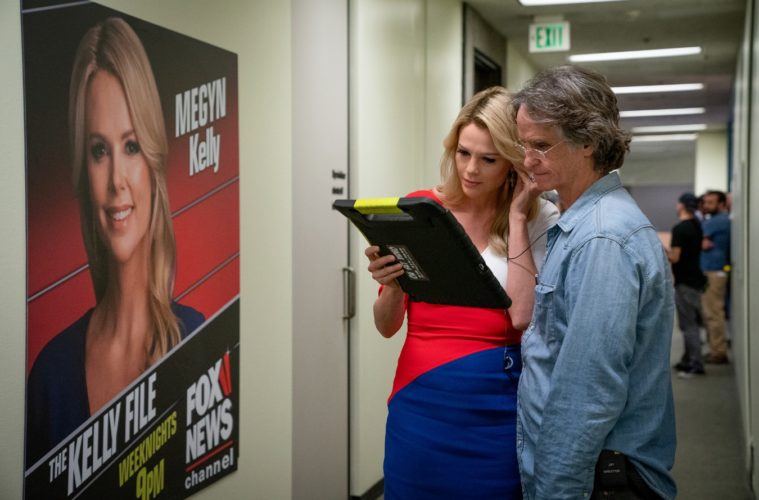

I use the elevator scene to illustrate that tension, because it’s the only scene in the film where all three women [Megyn, Gretchen and Kayla] are together—and it’s not by accident that this moment became the film’s teaser, because it stands for exactly what you just said: three strong and interesting women in this box that’s rising from the basement level up to the floor of Ailes’ lair where the harassment occurs, and none of them can feel safe enough to turn to the other and tell their truth about what’s going on. Each of them sense that something is going on—one has an old history with harassment, one has a relatively recent one, and the other is currently experiencing it—and the audience knows exactly what they’ve experienced. Yet they can’t support each other because Roger Ailes created a climate of fear; making them suspect that they’re being surveilled by one another, that they were replaceable by each other, and that if they spoke up, even the women might turn on them. Keep in mind that this was a year before the MeToo movement really kicked in following Harvey Weinstein, so although there was no dialogue, that scene spoke to me really loudly about the division and mistrust.

You really honed in on that atmosphere of mistrust once the allegations start to surface. You’ve described it as a kind of surreal atmosphere, filled with paranoia, side-glances, and an ‘every man for himself’ mentality. Had you spoken to former Fox employees to get first-hand accounts?

Yeah, especially regarding the perpetual surveillance. Not many people have asked about that—there really were video cameras everywhere. Roger had monitors in his office, but he was really watching how women treated each other, and whether they were loyal to him or not. There was an almost cult-like requirement of loyalty and fealty, where people had to pledge allegiance to Roger and the Fox brand—this was being observed constantly, kind of like undercover Gestapo agents that would check someone if they were going off-script or doing something that Roger saw as threatening, as in becoming a potential accuser. Anyone that fell under this category would be reported, and these ‘loyal soldiers’ as Roger would call them—including the “Team Roger” female anchors we see in the film, like Kimberly Guilfoyle—participated in character smears and assassinations, and would be quick to judge these women.

Had you spoken to any of those “Team Roger” anchors, which also included Ainsley Earhardt or Martha MacCallum?

Yes, two in fact, and they were very much on that team. Still to this day, to hear them talk about who Roger was and what Roger was like, as if it was just some old-school flirtation or normal bossing around, it’s really tragic actually. I’m conflicted between judging that kind of rationalization, but also feeling a sense of tragedy that they could be so clueless. It just reminds you of the lengths people will go to in order to reconcile their behavior. Megyn’s producer, played by Rob Delaney, is that kind of character who has the choice to believe Gretchen and believe accusers generally, but instead he takes the easy way out in order to protect his job.

One of the biggest themes of Bombshell is that power of compartmentalization. Those ethical contours were especially murky with someone like Megyn, who was at the height of her career and afraid she would lose it all, even though she had already wielded the immense power and legitimacy that comes with fame. By that point, she was far enough removed from those plebian indignities that she was able to consider Roger a friend. Can you speak to how you approached that inner and outer conflict with Megyn, given that predation relies on those kinds of power dynamics?

That’s a really good question. Holland Taylor, who plays Ailes’ assistant, represents the most extreme form of that kind of complicity—as she was basically luring young and ambitious women into his office to be preyed on. In her book, Megyn talks about feeling bad for having waited so long to go public—she actually didn’t even go public at first, she had just spoken to the outside firm tasked with investigating Gretchen’s claims, and that was leaked. Obviously she has since told the story quite publicly and frequently in support of Gretchen, but we weren’t easy on her in the scene with Margot Robbie’s Kayla, who confronts Megyn on her silence. Megyn’s response that it wasn’t her job to protect these women are the same sentiments she expressed in her book, but then ultimately she did realize that she had a moral obligation to speak up, and she did.

Bombshell is now in theaters.