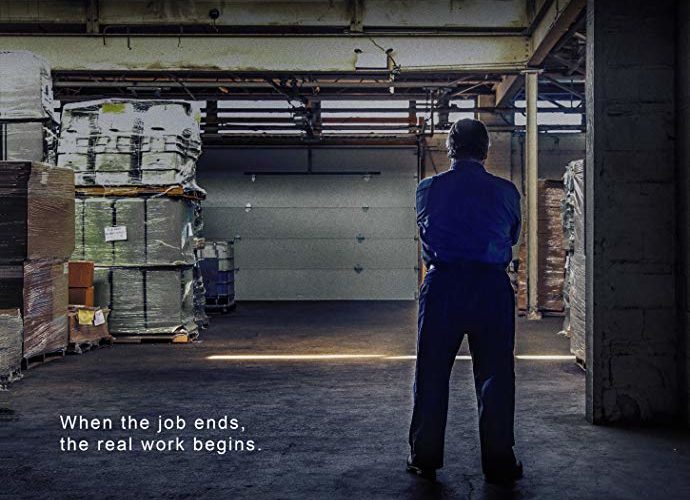

The title Working Man only deals with one aspect of Robert Jury’s film about the effects of a rust belt town’s last factory closing. Allery Parkes (Peter Gerety) is a “working man,” but his breaking-in to continue working without pay while his neighbors (also laid-off) think he’s gone crazy isn’t a product of compulsion. No, he does this because it’s the best excuse he has to escape home. As the opening prologue alludes with Allery calling his son’s name to no avail, this current version of him suffers from unacknowledged depression. He doesn’t talk to his co-workers anymore and his wife (Talia Shire’s Iola) can barely coax two words out herself. The job has therefore been his reprieve—a solitary task that stopped him from thinking about his loss.

Now it’s gone. Now he must sit at the kitchen table and listen to Iola discuss her plans for the day as though everything was normal. We never find out how long it’s been since Gabe passed away, but the intense frustration on his face this first morning after losing his job proves it hasn’t been long enough. So he gets his lunchbox and thermos ready, walks out the front door, and tells anyone who asks that he’s walking to work. While they laugh (and Iola worries), he forces himself in through a side door and begins cleaning the machines since the lack of electricity prevents him from turning them on. After three days of this, one man (Billy Brown’s Walter) stops by with an offer to help.

More than that, Walter stumbles into an opportunity that might get this factory operational again. Because it’s a risk and he’s the newcomer of less than one year, he presents the solution to their fellow factory workers as Allery’s idea instead. Since the latter doesn’t talk and is the person who went back without permission first, he’s the perfect face to go with Walter’s potential revolution. Even a skeptical Iola gets on-board because she sees what this glimmer of hope gave her husband—something he unfortunately wouldn’t let her close enough to provide instead. The town comes alive again and the single local news station puts a reporter on the scene to capture what he can (not too much). Will they get arrested? Or will the company flinch?

Like I said, though, this film isn’t solely about citizens discovering (in admittedly overwrought speeches) that so much of their identity and pride was connected to their ability to work. It’s not about social classes or economics either—territory Ken Loach mined beautifully in his I, Daniel Blake. This story has always been about Allery and that doesn’t disappear because Walter arrives with optimism and promise. He’s still a sad man floundering emotionally regardless of whether he’s been able to put on a better façade for those fighting this cause alongside him. And despite Walter flirting with becoming a “magical negro” archetype, his own journey reveals a similarly debilitating hurt too. Suddenly his role shifts from renewing Allery’s escapism to present both an unlikely second chance at life.

I won’t get into how this happens since that would spoil a rather dramatic reveal changing the course of the entire movie—a necessary one with the plot starting to forget “why” in order to show “how.” Jury understands this isn’t enough to give his character a satisfying conclusion, though, because the factory job has always been a Band-Aid placed upon the bigger issue facing Allery. He needs to pivot away from hope and expose this man’s despair in a way that forces him to confront his own vulnerability through that of another. It’s here too that Iola puts her foot down as someone tried of sitting back while her husband pretends nothing is wrong. She can no longer live as though they all died with Gabe.

Hard truths enter the equation and neither Allery nor Walter is ready to face them. What’s worse is that they can’t quite see past their own noses to recognize that helping the other move forward is a means towards helping themselves. Why would they, though, when all they now know is the sorrow and pain they’ve lived with so long? Iola becomes a crucial piece as a result because she can put a mirror up and show them how alike they are despite initial appearances. This epiphany happens pretty conveniently with that similarity falling victim to the feeling that its origins were a convenience specifically built for the narrative, but the heart is real. Gerety, Brown, and Shire are fighting demons and we appreciate their struggle.

This is key because Working Man lives or dies by our accepting these characters and the trials endured to (maybe) exit the other side with feet firmly planted on a road towards healing. You must see them as more than pawns in a capitalist agenda-driven game because that game is ultimately a pawn in theirs. Losing their jobs is tragic—as anyone in the rust belt knows—but their worries are rooted in something much deeper and more complex. Jury has crafted an internalized drama getting to the core of our values and the way we can become warped by them in the context of love and the guilt of being unworthy born in the process. Facing this reality demands hindsight and perhaps forgiveness in oneself.

Working Man played at the Buffalo International Film Festival.