When Tony Conrad passed away in April of 2016, I knew of him as an experimental filmmaker. It’s hard to be an art student at the University at Buffalo — despite his teaching in Media Studies rather than Fine Art — and not know his name. But that was all I knew: a name, reputation, and the plaudits of countless friends who knew so much more. Only when obituaries started being released in the likes of the New York Times did I realize how renowned a figure he was beyond local heroic status working alongside Paul Sharits and Hollis Frampton in my hometown. Then Rolling Stone posted. Pitchfork, Stereogum, NME, and other music publications quickly followed suit. Suddenly a whole world was opened by his sprawling legacy.

This is where documentarian Tyler Hubby arrives — with a film twenty years in the making that proves perfectly suited for a Conrad novice like myself. Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present is a crash course spanning his avant-garde New York City underground beginnings after studying undergrad at Harvard through his years teaching students how “not to learn” onto a renaissance of sorts that finally positions him as a leader in the minimal music movement. It focuses on his geniality, sincerity, and anti-establishment philosophies, touching upon the music and movies without delving too deep into the theory so as not to risk alienating audience members. Hubby’s film is Tony Conrad 101: a syllabus into one of the twentieth century’s most influential artists who you don’t know.

Seeing it with a crowd of ex-students, friends, and colleagues shines a light on this aspect for better or worse with almost every question being prefaced with, “Tony was assertive … difficult … etc.” — adjectives that don’t necessarily show onscreen. Hubby admits Conrad wasn’t the easiest subject where planning was concerned, eventually resigning himself to the reality that he was “capturing this specimen in the wild.” He was willing to assert control over the project in the edit, letting Tony perform for us in the documentary’s making as much as explaining the journey to that point. This piece is ultimately working towards cementing some of his life’s truths that have been clouded or silenced, so perhaps this version of Tony is sanitized to a point. But it’s no less intriguing.

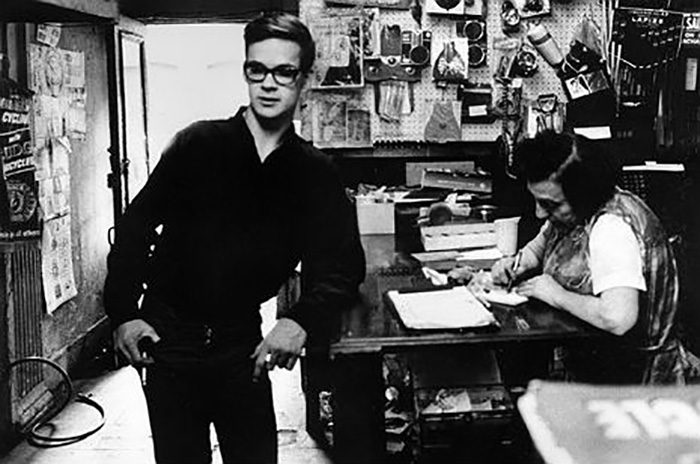

Do I hope Hubby eventually makes a companion film cobbling together the lengthy conversations about what his specific compositions and movies mean? You bet I do. But that isn’t as palatable a subject when you’re dealing with someone the layperson doesn’t know. I therefore appreciate this introductory experience first because it peels back the layers of history to reveal Conrad as an enigma not to be contained by one mode of creation while also excelling and transforming each mode he touches along the way. He performed with John Cale, La Monte Young, and others as Theatre of Eternal Music and / or The Dream Syndicate. He played with Lou Reed in The Primitives, helped form The Velvet Underground, and then left music (temporarily) to create seminal experimental film The Flicker.

That’s quite the pedigree in international terms without details providing more local worth as an educator and mentor, albeit with unorthodox methods. Always on the cusp of new technologies, Conrad worked extensively with public access television to break down the barriers of the media elite and help underprivileged kids engage in homework. He even Skyped into classes while on tour with his violin to connect the world in profound ways, no matter the reality that only forty or so people were experiencing the phenomenon. He was a singular entity revolving on an orbit all his own, and Hubby’s extensive access puts it all on film. We see the funny side of Tony, an innovator seeking to destroy the systems he worked inside while utilizing them to do so.

There’s a mixture of formats and quality like one would expect from a film centering on a career spanning half a century and myriad recording methods utilized within, all set to a soundtrack of Conrad’s own drone harmonies of sustained pitches readying to hypnotize us if we’re not too careful. Hubby includes excerpts from The Flicker and Straight and Narrow to give an idea of the disorienting state viewers experienced while watching and video work Conrad admits was made to force the audience into cultivating a dismissive attitude. If there’s one thing to take from watching Tony engage with his own past, it’s the gleeful delight he shows when talking about rejection. He wore every instance that viewers didn’t like what he made as a badge of honor.

In this respect, the film merely piques interest to jump down the rabbit hole that was his life, and remains an indelible mark on the art world at-large. The first thing I did after leaving the theater was search Spotify for his music; I’m now listening to Talking Issue in its entirety as a result. Hubby doesn’t really provide interpretation, motivation, or Conrad’s own self-criticism. Besides a single admittance of personal life regret, this is a straightforward depiction of unfiltered genius with little adversity, other than some authorship issues exacerbated by La Monte Young and more-or-less defended by the devotees and historians Hubby interviews. It’s a heartfelt memorial for us to meet Tony. Experiencing and dissecting the work left behind further is next semester’s independent study.

Tony Conrad: Completely in the Present played at the Buffalo International Film Festival and opens on March 31.