It’s hard to believe America’s first black Supreme Court Justice hadn’t yet earned the big screen cinematic treatment until now. Besides Thurgood Marshall appearing as a character in a few TV productions (including HBO’s Emmy-nominated one-man play Thurgood starring Lawrence Fishburne) and two movies (The People vs. Larry Flynt possessing the highest profile), this iconic hero who successfully argued Brown v. Board of Education in front of that same Supreme Court was all but invisible. And that ubiquitous 1954 moment interestingly isn’t even the one screenwriters Jacob and Michael Koskoff chose to adapt as Hollywood’s first mainstream look at him. They decided to go back even further to 1941 so they could highlight the hunger and fight of a young man on the cusp of changing the world.

The case: Connecticut v. Joseph Spell wherein a black chauffeur was accused of the rape and attempted murder of his employer’s wife Eleanor Strubing. By all accounts it was an open and shut case considering the defendant was an uneducated man without a penny to his name that left a wife and children in Louisiana, was dishonorably discharged from the military, and recently fired from his last job (but never charged) for stealing. His word against an affluent member of a well-connected family represented by a district attorney being groomed for the Senate in front of a judge who used to work with said prosecutor’s father? That’s the definition of slam-dunk if not for the NAACP sending their best man to gauge Spell’s innocence and take the case.

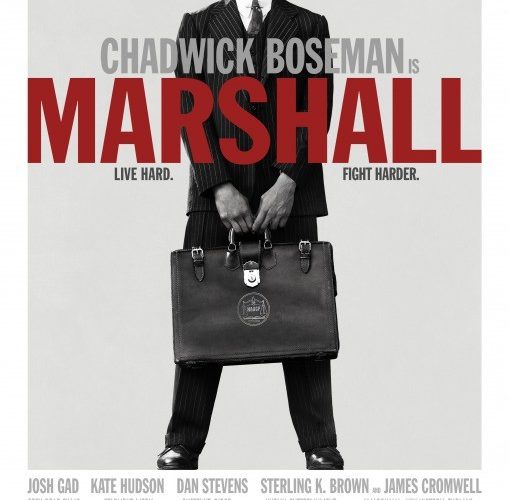

This is the setting for Reginald Hudlin’s Marshall. And if you recognize that name from his early films (House Party and Boomerang) and recent sitcom work, you wouldn’t be wrong to wonder why’d they get a comedy guy to helm a courtroom drama. The answer comes rather quickly, though, once the hoops needing to be jumped through for a New York attorney to argue in front of a Connecticut jury are revealed. Marshall (Chadwick Boseman) must be petitioned by a local lawyer and subsequently accepted by the judge (James Cromwell’s Foster). Finding someone to do this in a rich city with a 1941 racial climate isn’t easy. Some bamboozling might be necessary to coax assistance from an insurance litigator who wants nothing to do with the unavoidable exposure.

That man is Sam Friedman (Josh Gad) and his inexperience isn’t lost on Marshall—it’s coveted. Thurgood will need all the help he can get and a white advocate willing to do whatever he’s told is priceless. The result, however, leads to inevitable friction in no small part due to Marshall’s constant trolling. If the Koskoffs’ script is to be believed, he had one hell of a wry sense of humor. Boseman and Gad’s rapport in this way is nothing short of fantastic for the entire duration of the film, it’s biting severity tempered by a constantly growing mutual respect. One could say the proceedings are just as much or more about Marshall stewarding Friedman onto the career path he’d eventually lead as it is about Spell’s case.

There’s also much to be said about race where Friedman is concerned as a Jewish man considering World War II ramping up. We watch as the city he calls home turns on him and the strength he musters to combat the ever-escalating hate. Hudlin and company sprinkle in many little asides whether it Friedman’s wife understanding just how racist her community is despite being oppressed itself or locals growing enraged at the sight of a white woman (a brief but effective Sophia Bush) hitting on Marshall at a bar. These are the moments that really help to color the time period and the stakes involved. Some find themselves cutely harboring epiphanies in seemingly throwaway lines, but this device effectively moves things along no matter how contrived.

And that brings us to the case itself, the “he said/she said” between Spell (Sterling K. Brown) and Strubing (Kate Hudson). The truth is of course much more complicated than a single lie and it becomes Marshall and Friedman’s job to expose exactly what’s involved. I’ll let the film do this itself considering the shrouding of information plays a key role in the characters’ motivations and in-court chess match against the prosecutor (Dan Stevens’ Loren Willis). What I will say, however, is that Brown becomes the heart and soul of this film almost from the instant he is introduced. Here’s a broken man without the means to even hope freedom is still on the table. Why sully his innocence and admit guilt if a plea means eventual release?

The driving force behind everything he does is fear. When the benefit of the doubt unjustly lies in the hands of someone who appears more trustworthy because of the color of his/her skin or the gender of his/her birth, hope for equality becomes a luxury you simply cannot afford. And before any dude-bro sexual predator sympathizers out there take hold of this film as evidence of their MRA agenda that women “lie about rape,” know that Hudlin and Hudson do well to ensure we understand she is also a victim here. Marshall gets very good advice early on from a female acquaintance to the tune of, “Why would a woman fabricate a rape?” Strubing’s statement isn’t because she hates Spell or his race. It’s a matter of self-preservation.

This hard truth is Marshall‘s best attribute because the film becomes your regular run-of-the-mill courtroom drama without it. I wouldn’t blame anyone for saying it’s exactly that either way, but I do personally believe it’s more memorable than this train of thinking allows. Yes, it hits all the civil rights beats and hinges on the two-dimensional villainy that is a product of insular and bigoted upbringings, but it’s all true. You can’t fault the story for being “clichéd” when those moments that feel like forced adversity or opportunistic victories are authentic. If anything this is why the story is important: it shows us that books cannot be judged by their covers or past actions. When the evidence is presented, humanity still has the ability to overcome any prejudice.

It’s this lesson that renders the whole a success. I’d love to say the setting does too, but the simple fact that I’m a Buffalonian stops me. Until more Hollywood fare uses Buffalo, New York as its backdrop, separating reality from fiction will remain difficult. Everything probably looks great and unobtrusive to outsiders (our architecture is first-rate), but my knowing it so intimately lends a “fake” sheen. Thankfully the acting transcends any surroundings as Boseman brings this badass attorney oozing warranted confidence to life opposite Gad’s non-confrontational everyman experiencing the true power of his occupation as a result. And Brown steals the show with an emotional turn able to earn empathy from the most jaded audience member like Spell did Marshall. It’s time new generations learn Thurgood’s name.

Marshall screened at the Buffalo International Film Festival and opens on October 13.