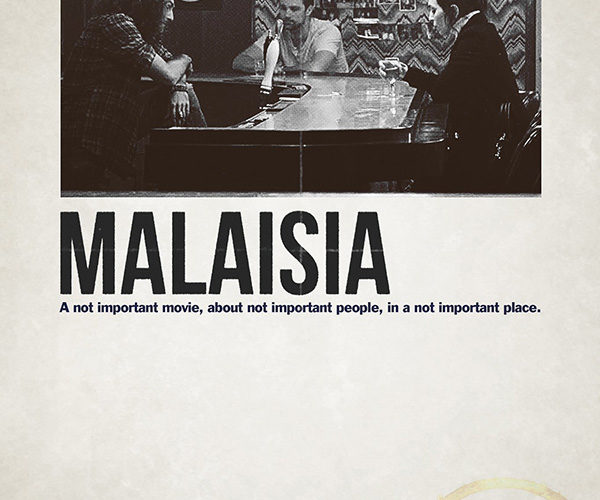

There’s a joke told about a third of the way through Mac Cappuccino’s film Malaisia. It’s bad. Jay Schmidt is the one laying out the excessive amount of exposition while his compatriot (Kevin Guzewich) looks on in exasperation—at one point even interrupting his interminable drone with an interjection to break up the monotony. On and on it goes and we’re unsure what to think as viewers since we haven’t even seen these two characters since the very first scene wherein the roles were reversed and the joke marginally better. The humor takes a nosedive into melancholic introspection before a sharp left turn to a punch line as bluntly eye-roll inducing as “A pig fell in the mud.” And Guzewich inexplicably laughs anyway with genuine praise. It’s weird.

I let the scene fade away due to its seeming insignificance beyond the promise of a robbery they love planning but refuse to execute. The men are grounding wires for a triptych retelling of a few days in Gwen (Sarah Baskin), Art (Leonardo Santaiti), and Lance’s (Josh Nuncio) lives. They introduce the bar for which a majority of the runtime is set and return to mark two rewinds that allow us to watch what’s already occurred from the other lead characters’ disparate perspectives. And we eventually reach a nexus point climax where everyone converges for a conclusion so off-the-wall bizarre that you can’t help but laugh. That’s when I realized the joke wasn’t random. The joke foreshadows the film’s construction and, to my surprise, is funny after all.

Nothing Cappuccino does is therefore without intent even if it remains shrouded under darkness until the final fade to black. But even that can’t necessarily be trusted since there are enough fades throughout to render the story into a series of very brief vignettes setup to simultaneously exist as individual episodes and crucial progressions from one to the next. Think of them as the closing of sleepy eyes made heavy by too much alcohol (Gwen and Lance) or too many expectations (Art)—everything that precedes them a figment of a mind operating well below its threshold for clarity. So actions play out completely differently depending on which character is in control, each letting his/her wants, desires, and paranoia color the others’ attitudes and intentions. There’s one constant: love.

While Gwen and Art are in a relationship and Gwen and Lance share the parallel baggage of unrequited desire for the other, however, I don’t mean love in a person. The emotion here is about happiness and how none of them have achieved it despite the desperation they possess in order to find its elusive existence. Gwen wants to be with someone who understands her and supports her as more than a checklist item. Art wants rock superstardom and will embrace any cliché he must to let it happen through osmosis rather than hard work. And Lance wants companionship that doesn’t come from the bottom of a bottle. They want what the world won’t provide because they won’t open their eyes to what’s keeping them back.

Or will they? That statement makes it seem there’s a correct path towards happily ever after if only they’d take it, but things aren’t so objective. Much like the art on display (Gwen is a painter whose latest will either be her ruin or success, Art is a musician who cares more about what record executives think than fans or bandmates, and Lance is a fledgling comedian whose jokes carry too much philosophy and not enough laughs), interpretations are subjective. Just because I think Schmidt and Guzewich’s deliberately told wisecracks lack humor doesn’t negate the fact that they enjoy them to a sickly sweet degree. Maybe Gwen, Art, and Lance simply need more time, luck, and courage to find their answers. Maybe fate is in the driver’s seat.

So it’s difficult to objectively judge what’s happening. While I was invested in the three-piece narrative and how what’s happening in each of their respective lives infers upon their decisions, presenting it this way doesn’t have any significant payoff. We know from the beginning that Art cares more about “what” Gwen is than her as a person. And we know that she and Lance have mutual feelings Art’s presence has made impossible to express. Viewing their days in triplicate doesn’t change that knowledge or add anything new to the equation. Those few moments that exist in one but not the others could have just played out naturally with the repetition culled to shorten a barely two-plus hour runtime. The structure’s value arrives in its ability to distract instead.

Cappuccino is intentionally walking us around convoluted circles because it keeps us invested in what we see and ignorant to what we don’t. He allows his actors to showcase their skills (Baskin, Santaiti, and Nuncio are all very good), lets his characters have their moment to unleash a pent-up rage they keep poorly hidden in the others’ memory, and gives us nothing to latch onto as far as how he’ll end everything beyond the inherently melodramatic fallout love triangle films always have waiting in the wings. Where he goes to supply his leads what they crave (albeit in off-kilter ways) won’t satisfy everyone, but even his detractors must admit that taking the risk to alienate his audience was a bold maneuver. And he embraces it with unrepentant delight.

Malaisia played at the Buffalo International Film Festival.