Everyone’s family is crazy. Some may seem crazier than others, but that’s generally a byproduct of them being less self-conscious. The question we don’t ask ourselves — whether a part of the insanity or watching as an outsider — is why. Why does one member prove so gratingly obnoxious when you know he/she knows what others think? Why does another member retreat into his/her insular existence away from the sprawling chaos so that any opportunity to join the others feels like a chore? What has happened to drive this wedge that grows larger with each passing year of silence? The answer usually concerns blame. To be so close to someone when something bad happens to you both requires empathy and understanding. Guilt, however, often forces us to find fault instead.

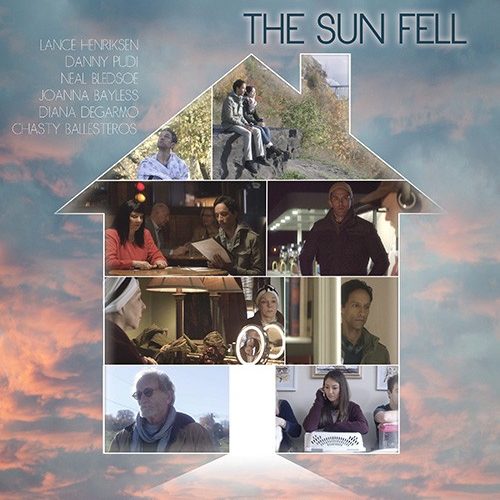

This is why Brandon (Neal Bledsoe) dreads returning home. He never wants to endure the circus longer than necessary, but has to go and risk being trapped nonetheless. His current visit stems from the fact that he’s about to ask his girlfriend (Chasty Ballesteros’ Yuan) to marry him and hopes to acquire his grandmother’s ring for the proposal. That means asking his mother (Joanna Bayless’ Mary) to gift it to them despite never having met her potential future daughter-in-law. She doesn’t even know her name. So Brandon is anxious. Embarrassed by his parents (Lance Henriksen’s Dicky rounding out the duo), he always assumes the worst when change is involved. And since a buffer might help, he invites his friend Adam (Danny Pudi) along to conveniently siphon off attention.

Unfortunately, the tragedy haunting this family is directly correlated with there being three members where four had once resided. This means Adam’s presence can potentially open wounds they’ve taken pains to keep closed for far too long. So while he sought to escape his own reality of having just broken up with the girlfriend whose apartment he called home, Adam ultimately becomes an unwitting conduit for ancient drama not yet reconciled. In their own unique ways, he becomes the son Brandon’s parents had lost. Adam’s migraines trigger Mary’s maternal instincts, her warped desperation rising to coddle him and pretend he’s her Travis. And his proximity ignites Dicky’s combativeness, providing a figure to prop up as psychological opposition to Brandon like he used to with his deceased son.

The message writer Jonathan Caren (adapted from his own play) and director Tony Glazer seek to embody is one of filling voids. Their process is a bit on the nose considering a literal hole in the roof of Brandon’s family home exists as a direct reference to Travis’ absence. But After the Sun Fell (the title is perhaps a misplaced pun) does also possess nuance. You just have to sometimes wade through excess to get it. I can point to a dinner scene between Mary and Adam meant to bolster the over-the-top loquaciousness-bordering-on-hysterics of the former that doesn’t provide much we didn’t already glean beforehand. Its eventual culmination towards a blow-up between Brandon and his mother is crucial, but Adam’s simultaneous hallucinatory disorientation distracts rather than enhances.

There are multiple instances like this including an entire secondary character that doesn’t add nearly as much to the whole as her appearance seems to initially intend. While Piper (Diana DeGarmo) arrives as a voyeuristic outsider like us — an employee of Mary’s who is helping to clean the house — Adam steals that role away rather quickly. Suddenly Piper becomes little more than reaction shot model save a subplot concerning the aforementioned ring and a timely line of dialogue that sparks epiphany towards the end. But whenever she isn’t necessary to propel the plot forward in ways that could have been rewritten without her, she’s gone. The simple fact no one asks where she’s went only confirms how her character is always more device than living, breathing person.

Strip away this clutter, though, and a ton of heart is revealed. The impact of Travis’ death is forever present in Mary, Dicky, and Brandon’s actions, its story hijacked by each in order to supply half-truths that ignore their own personal roles in what happened. Adam is therefore the clean slate untainted by one version over the other. So he listens to the arguments and sees the pain. He pieces together the truth in a way that lets him be an active participant as far as stirring the pot just enough to force them to confront each other. This arrives with more superfluity — Adam uses his experience as creative inspiration for a comic Glazer brings to life through three random thirty-second animated snippets — but also packs a punch.

Henriksen and Bayless are the standouts as their characters’ emotional upheavals are the most resonate and pure. One of their sons died and the other left them to pursue his life. They don’t begrudge that decision, but his absence did make living without Travis harder. Dicky became quieter and frustrated while Mary grew louder through her constant inebriation to fill the silence. They’ve driven each other mad as a result, their lack of outside interaction exacerbating these new identities until they’ve lost all perspective. Brandon’s appearance therefore forces them together, the resulting awkwardness and unpleasantness proof of how much their son has missed. And his desire to get the ring and go tells them he’s as much ghost as Travis — worse even because he’s choosing to stay away.

But Danny Pudi is the star, his Adam the stubborn glue holding a mirror onto them so they can no longer hide from the animosity and guilt defining their lives. He’s a spark plug in this way, a catalyst whose problems become inconsequential once he discovers the reason why he’s there. This trip starts with him as the fifth wheel postponing his search for a new apartment and ends with him as a puppet master pulling the strings to uncover civility and recognition. Adam’s presence rekindles a dynamic that had been erased, his inclusion allowing the other three to finally acknowledge the façades they’ve constructed. He reminds them that healing is possible if they stop letting anger and self-hate guide their actions. That’s a hard truth to bear.

After the Sun Fell screened at the Buffalo International Film Festival.