Fatih Akin’s latest movie is a fetid stain on the CV of a good filmmaker. Akin has made the true story of a repulsive, grotesque serial killer into a repulsive, grotesque movie, a calamitous misfire for a critical darling of recent German cinema. This is a film that wallows in the most appalling sexual abuse, that fetishizes facial disfigurement and physical deformity and, most cowardly of all, gives no voice to women who were the victims of horrific historic crimes. Set in the early 1970s, it offers a view into many of the trappings of that era’s misogyny, but gives nothing in the way of ironic retrospection or insight–especially inexcusable in today’s #MeToo era. The House of Jack Built, released to indignant uproar last year, is a profound statement of human condition by comparison.

Based on a non-fiction novel by Heinz Strunk, this is the story of Fritz Honka (Jonas Dassler), a real-life killer who murdered at least four women in Hamburg’s red-light district and left dismembered body parts festering in a spare room of his apartment. A vicious, alcoholic sexist, he preyed on sex workers and the most destitute women who frequented a rotten local working men’s bar that bears the film’s title. Akin’s aim perhaps was to focus on the underside of Germany’s post-war economic miracle, emulating the likes of ’70s filmmakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder, but while his work often depicted a cruel, indifferent universe, movies like Fear Eats the Soul offer a font of human insight. There is none here.

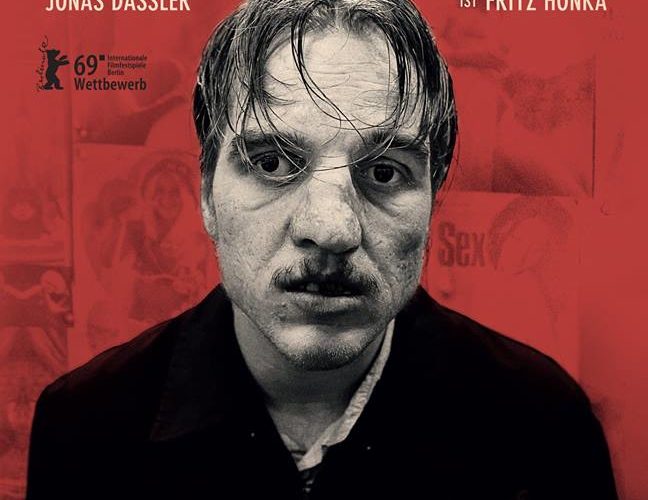

Under layers of makeup that gives him the look of an eczema-ridden rancid gargoyle, 22-year-old Dassler gives it his all, playing the much older Honka as a prowling, hunchbacked creep. The film fetishizes his facial disfigurement, his squint and his wretched limp, and at the very least is complicit in a repulsive fixation of physical attributes. This is a film in which the camera is an accessory to Honka’s sexist worldview, that argues beauty is the height of moral achievement and physical ugliness should be disposed of.

What Dassler’s performance offers in expressionistic talent–notes of Peter Lorre in M are surely no accident–it lacks in self-pity, self-reflexion, and remorse for his character’s violent misogyny. This is a man whose repugnant worldview appears fully formed, where emotional context is discarded in an effort to provide morbid immediacy. Within the movie’s first five minutes, Honka has already sawed off a naked woman’s head, chucking discarded body parts into a plastic bag that he disposes of in local dumpsters. In another scene, he forces a concentration camp survivor as his slave (mercifully, she is one of the few who escapes). Later, he strangles a woman in a scene that lingers as if for eternity. At least Akin has taken some effort in the production design here–Honka’s nightmarish apartment is a dank, harshly lit, where pine-scented needles hang from the ceiling to mask the stench. The set design looks like it was given far more time than the spineless script, which offers women characters little in the way of voice, passive victims to be discarded of in service of the film and Honka’s plot.

So why did Akin make this movie? It is simply head-scratching that this is the same filmmaker as the one who made Head-On and Edge of Heaven, or the one coming off the acclaim of his last film, In the Fade. I imagine that among the nauseating bloodletting, there’s a buried satirical statement–after all, Honka got away for so long because society didn’t care about the people he killed. The fatal problem here is this film doesn’t care about those people either.

The Golden Glove premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival and opens on September 27.