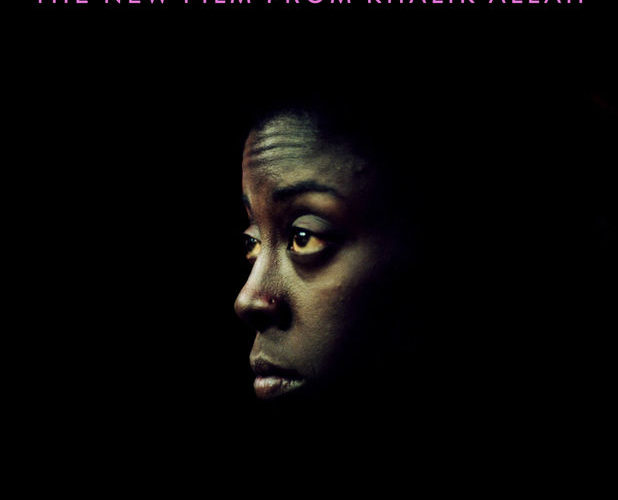

Photographer Khalik Allah has been documenting down-on-their-luck New York denizens on the streets for several years. During the summer of 2014, Allah swapped his still camera for a video camera, and set about shooting life at the corner of Lexington Avenue and 125th Street in Harlem. But Field Niggas is nothing like a typical documentary that “profiles a milieu.”

Allah recorded audio and video separately. While the characters speak about their religious beliefs, or their opinions on current events, or just how their day went, slow-motion imagery plays across the screen. The movie tends to focus on blowing up the smallest gestures, such as hands rolling a K2 blunt or walking-and-talking arguments. Most often, it’s simple shots of people — the homeless, the police officers, the pedestrians — merely looking the camera in the eye. The disconnect is only momentarily disorienting, and, after the viewer adjusts, it helps make the documentary extraordinarily hypnotic.

Any sense of narrative structure is eschewed. The various snatches of dialogue could barely even be called vignettes, since there’s rarely anything approaching a full conversation. This vividly evokes the feeling of walking a city sidewalk at night, overhearing brief parts of other people’s lives with every pause at a crosswalk or bus stop or simply to take in one’s surroundings. Reinforcing this is the brilliant digital camerawork, capturing every variety of night blacks and hazy lights. So, too, does the scant, hourlong runtime — about the length of any walker’s commute.

Field Niggas takes its name from a Malcolm X speech. It was filmed over the summer in which Eric Garner, a black man, died after being put in a chokehold by white police officers over the sale of unlicensed cigarettes, inflaming racial tensions already stoked by similar incidents across the country. All of the subjects are people of color, most of them homeless. Politics are in this documentary’s bone marrow. These are the people crushed deepest into the pavement by institutional racism and classism: many of them talk about their own run-ins with police, how their mere existence is a matter of navigating behavioral hazards.

Allah only missteps towards the end, when he gives the closest thing the film has to a full-on speech. Throughout the documentary he repeatedly affirms his love for all people (including the police) to his interviewees. His goal, as he makes clear, is to create a better understanding between all people. The closing is him restating this, and comes not long after a title card paying tribute to Eric Garner. But given that there doesn’t seem to be any interviews with police (only glimpses of their unfriendly, wary faces), this is more of a disclaimer than anything else — a preemptive heading off of criticism that the film might be somehow energizing anti-law-enforcement sentiment. Empathy is better felt than claimed, and Allah’s interventions into this material only muddle an experience that, otherwise, is purely felt.

Field Niggas screened at AFI Fest 2015.