In an episode of my podcast, The Cinephiliacs, colleague Vadim Rizov noted a humorous but mostly essential statement when describing his disappointment with the movement of the Duplass Brothers into more mainstream territory: “Bros need independent movies, too.” Most depictions of “bro culture” have depended on some of the loudest names in Hollywood — Judd Apatow, Adam McKay, and Seth Rogen among others. The problem is that these bro movies often seem to focus on the pleasures and perils of being a bro — a subject only worthy of intermittent screen depiction — and few of them use that milieu to explore other factors.

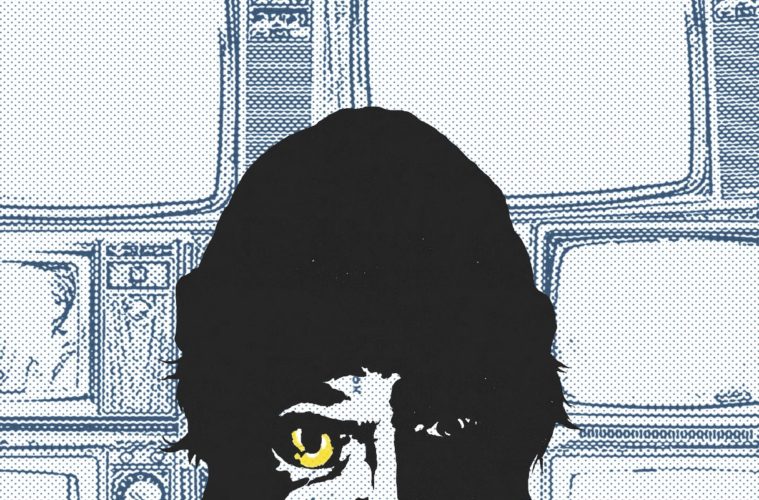

That’s what makes Buzzard, Joel Potrykus’s second feature, one of the most exciting pictures in contemporary American cinema. Starting with an oft-kiltered shot of its main character’s hand breaking a Nintendo Power Glove, Buzzard is a truly uncomfortable sit featuring an asshole who pushes everyone’s boundaries. But unlike the similarly designed The Comedy, Potrykus’s film explores essential class issues at the heart of this film. While set in a social milieu of Grand Rapids in an unspecified time around the late ’80s or early ’90s, Buzzard is a film obsessed with the post-recession, post-NSA era. It’s a film littered with money (or the lack of it) that recalls neo-realist greats, but not by making a film about the toils of the human spirit. Instead, it takes the form of the previously mentioned bro genre, and peppers each one of its moments with stunning accuracy and an extreme paranoia. It’s a film that understands the post-recession American dream is a bowl of spaghetti and meatballs instead of two microwaved Hot Pockets.

Buzzard follows the world of the standoffish asshole Marty (Joshua Burge) in his shitty existence as a temp for a local bank. What Marty mostly does is scheme money. He attempts to close and open a bank account for the free $50 offer. He calls in coupons on the back of pizza boxes. He returns office supplies bought on the company card for cash. Most importantly, he schemes a plan to cash undeliverable tax returns from his bank. Buzzard’s working class milieu is not one of desolate poverty, but utter tedium. Potykus captures Grand Rapids (and later Detroit) with little flair, emphasizing its monotonous lighting, littered locales, and only the punching sounds of Marty’s hard-metal tunes to add any character to a lifeless universe.

What makes the film compelling, however, is not just Marty (and Burge’s absolutely committed performance), but the way it depicts the delusions of the working class in its era. Throughout the film, numerous people offer Marty tips on how to make life more convenient (and thus more profitable) to him, not realizing he will use those tips to essentially abuse and steal from the system, and at points finds himself a victim of the same scheming. Marty’s co-workers are equally unaware of how little they can progress out of their social strata — the secretary temp, Sharon, boasts about being brought in full time to her $10-an-hour position, while Marty’s best friend, Derek (played by Potrykus), talks up his new “party zone,” which turns out to be little more than a TV with Sega, a couch, and a colorful moving lamp (in his dad’s basement). In the party zone, Marty and Derek essentially “bro out,” playing video games and doing stupid shit like a game involving eating chips off a treadmill (delivered in a hilarious, long-take close-up) and slashing each other with violent objects. The lack of inertia or plot during these sequences conveys both the comedy (Potrykus’s shooting style sneakily frames things for the highest laughter) and the utter disparity of mobility of their social strata, as they regress into their 10 year old selves.

From there, Buzzard moves into a more surreal territory, but never loses its focus on and obsession with the frantic paranoia of survival. The film hits a climax as Marty checks himself into a just-above-average hotel room, eating a plate of spaghetti while sitting on a big, clean(ish) bed and watching cable TV. As shot in real time, Marty allows the spaghetti and meatballs to pour all over his face and body, a moment of true happiness that captures the apex of Marty’s goals and desires in life while also emphasizing how his ideological environment has stunted any potential he may desire. That the next night is spent in a drabby motel, eating cold Spaghetti-Os from the can, only emphasizes the bliss that came before. From there, Detroit slowly becomes a nightmare situation, where the necessity to survive becomes an uncertainty, and the world of surveillance cameras that infects every part of reality shows there is no possibility of escape.

Buzzard takes pages out Taxi Driver, Mauvais Sang, and other greats as the film reaches its conclusion, where Marty’s violent outbursts are less a psychological push than one, as the title suggests, of animalistic necessity. Potrykus may be a cinephile director who wears his influences on his sleeve (look for a prank involving a copy of Cinema Scope Magazine casually placed in a 7-11 magazine rack), but he uses genre tropes — bro comedy, realist long takes, and surreal horror — to investigate the state of this social milieu. Buzzard might hit an important note of zeitgeist in its depiction of America, but what makes it phenomenal is the lack of grand statements — it simply focuses on a life without hope, which, thankfully, can still be a source of humor.

Buzzard screened at AFI Fest and will be released by Oscilloscope Pictures next year. See the trailer above.