Let’s start with this obvious point: few cities need another repertory outlet less than New York City, which provides enough decent-to-outstanding options every week (or day) to fully occupy any caring customer. And so when a new theater, Metrograph, was announced this past August, the largely enthusiastic response — people taking note of a good location, a dedication to celluloid presentations and new independent releases, its strong selection of programmers, and other services (e.g. a restaurant and “cinema-dedicated bookshop”) — went hand-in-hand with some people’s skepticism, or at least a certain raising of the eyebrows. The question of necessity was premature, but such is the influx of available material that it should inevitably come up.

It’s safe to say their first selections silenced those skeptics. Metrograph’s slate is strong in a way that’s uncommon; one could say it’s exactly the sort that a cinephile with love for movies of all shapes and sizes would imagine while “understanding” their dream is unlikely to ever come true. Having drafted a weekend repertory calendar for the past few years, I’ve seen many items, be they individual films or massive series, come and go, and the quality that stands out most is mixing the familiar — or, at least, the widely liked — with rare and esoteric titles so many wish to see in a theatrical environment.

I was fortunate enough to visit their office last week, where I found a small, impressive team at work. Metrograph’s Artistic and Programming Director is Jake Perlin, a programmer, distributor, and producer with years of experience at BAM and the current manager of Film Desk, which specializes in the restoration and distribution of foreign classics, along with film-related books. (The Truffaut one is a real delight.) Positioned as Head of Programming is Aliza Ma, formerly of the Museum of the Moving Image — a favorite moviegoing destination for New Yorkers — while Michael Lieberman, as well-trusted as any publicist in this city, works as Head of Publicity, and Michael Koresky, editor-in-chief of Reverse Shot and staff writer at Criterion (cherished totems of cinephilia both), is director of Publications and Marketing, a task relating to the numerous capsules in Metrograph’s emails and on their just-launched website.

There’s no doubt we’re looking at a reliable team right off the bat, a sense that grows stronger when sitting in the office for just 90 minutes some seven days before the theater opens. At this time, the environment is undoubtedly active, not hectic. If a lot of things are happening, they appear (to my eyes) to be happening at a good tempo — or so I’d think of almost any place where “two prints from Pennebaker’s office” are casually laid next to a stack of prints for Eyes Wide Shut (personally selected by Noah Baumbach for his dream double-feature with Babe: Pig in the City), The Long Day Closes, and perhaps one other masterpiece I’ve forgotten.

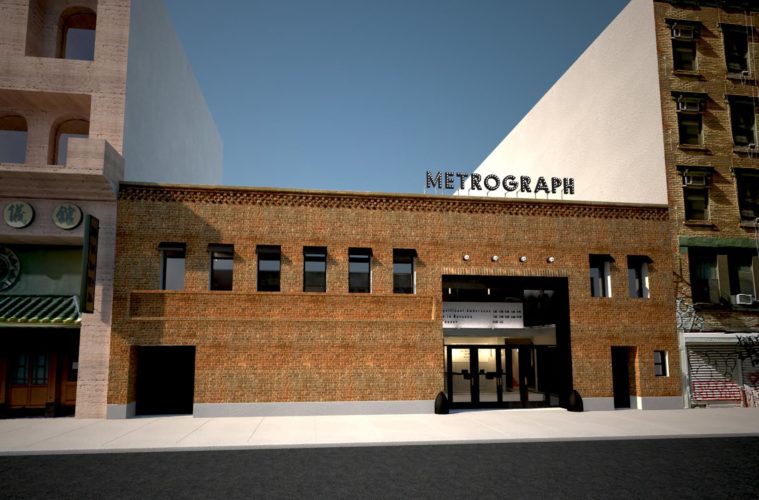

A knowledge of cinema, passion for the art of programming, and the ability to discuss these things in-depth are signs of a fine start, and their effect is almost immediately mitigated if there’s no proper space to support that energy. Good news: even in a not-100%-finished state, the theater — founded and designed by Alexander Olch — impresses a great deal. While I can’t speak for presentation, it’s nonetheless clear that Metrograph’s two theaters are well-sized: one, equipped with a fine balcony, is almost certainly the largest place in which you’ll ever see the likes of Johnnie To’s Office 3D and Tsai Ming-liang’s Afternoon, two exciting first-run titles, while the other screen is both admirable in scope and, as Lieberman noted, a proper setting for the more “vertical” 1.33 frame in which several of their titles were composed. I think it’s worth noting, too, that those with no interest in concessions, a bar, a restaurant, or a bookstore need not worry: upon entering, one can walk straight to the box office, take a handful of steps towards the theater, and make a direct exit once the picture’s ended.

Presented below is an extensive interview with Perlin, in which we discuss why Metrograph matters, the impetus behind certain programming decisions, the nuts and bolts of that practice, and where he provides an in-depth look at how their unique showings come together.

The Film Stage: You’ve certainly been immersed in the NYC film pool. Here’s a question that might lead right into things: did you observe that world — what plays, what people see, etc. — and decide there were things you wanted to do differently, or simply better?

Jake Perlin: I mean, I don’t like to say “better,” but “different.”

Jake Perlin: I mean, I don’t like to say “better,” but “different.”

Then what makes you stand outside the rush of programming?

Even before I was programming with an institution, when I was just putting on programs at this place on Ludlow called Collective Unconscious, or a place in Brooklyn called Galapagos, the Alliance Française, where my friend Marie Losier programmed — all places where I asked people, “Can I have the space for a night and do a program?” What was motivating my desire to do that was that I wanted to show stuff that I thought wasn’t being shown, right? Or stuff that interested me that I wanted to share that wasn’t happening other places. Or, if it was, I wasn’t aware of it, or maybe it happened five years earlier — whatever. It wasn’t groundbreaking stuff, but it was just stuff that I wanted to do. In that sense, it was trying to do something different. So I say to myself, “Oh, I want to show a bunch of movies that are on Cuba and made by non-Cuban filmmakers.” Or Marie and I are sitting around at the Alliance Française, saying, “Wouldn’t it be cool to invite Raoul Coutard to America?” And then we invite him to America and do a whole retrospective of the films he shot.

So I think it’s really just following your own interests and figuring out what other people are interested in as well. That was very early, but then… I guess Film Desk is a good example, too, because there are certain films that are really great and have fallen out of distribution, and you wonder, “Wait, no one in the United States owns Monsieur Verdoux? No one has ever released a Garrel film before?” You’re not looking to be the company “that releases the Garrel film.” You go to France, you see it, you love it, and you come to realize that very few people have written about Garrel in English. There was limited stuff a decade ago, and you get more interested in his work and think, “Holy shit, I could do something about this if I scrounge together a couple of thousand bucks and do something about it.”

But, yeah… I guess it’s just about following what your interests are, and your interests are probably increased by their inaccessibility sometimes. Or just a realization that, “Wow, no one owns Truffaut’s The Wild Child.” So I don’t know if that exactly answers the question. It’s not, “What can we do that other people aren’t doing?” It’s not, “What can we do that’s ‘different’?” It’s most just, “We want to do our thing, and the byproduct of the thing we want to do is probably something that hasn’t been done.” And then, more specifically, it’s like, “Well, there’s this experience we all share of going to the cinema. What do I like and not like about that experience?” When you build a website, you’re basing that on what you liked in other websites that you’ve navigated before, successfully or unsuccessfully. When you build a movie theater, you think, “What kind of room do I want to be in? I want to watch movies every day. What kind of room do I want to be in?” And then you try to figure that out. We’re not reinventing the wheel. We’re just sort of updating and maybe refining it.

I mean, one of the things you’re leading off with is a Jean Eustache retrospective. Alliance Française pretty recently played The Mother and the Whore, but it isn’t exactly something that earns a reaction along the lines of, “Oh, that’s playing again?”

Right. Exactly. But also because we knew they were playing it, and they knew we were playing it, and we’re friends, I think we were able to discuss it in a way. First of all, it’s not a movie that can’t be shown “too much,” because it’s so rare, and I think that’s a film that can sustain a couple of extra shows on the Upper East Side before it plays downtown. It’s going to be okay. Maybe, for certain other titles, you’ll be more rarified. But you’re not going to fight over The Mother and… it’s The Mother and the Whore. You know what I mean? It’s fine. [Laughs] The Mother and the Whore is going to be just fine. I appreciate you saying that, but I do think there is a conscious thing where you sort of develop a sense, either among colleagues or just internally, about what the audience exists for.

The Mother and the Whore — I’m happy they played it. Who’s going to see The Mother and the Whore and say to their friends, “That shit sucked. Don’t.” Someone’s going to say, “Holy shit, you’ve got to see The Mother and the Whore. I want to see it again.” But I’m happy it felt that way to you, because one doesn’t want to seem like they’re doing things by rote. Even if things are familiar. Like, we’re showing Singin’ in the Rain, a film that shows a lot. I think we’re doing something by pairing it, on the same day, with two other films that are also showing in IB Technicolor Prints — Vertigo and Hatari!

And you don’t often see Hatari!, either.

Yeah. Just… there are no words for that movie. Right. Singin’ in the Rain can sustain a lot of multiple viewings; it’s a film a lot of people want to see. I hope that people will realize it’s something we really thought about when we decided to pair these three films together. It’s not just because they’re IB, but because we thought all three represent an ultimate of what those filmmakers were trying to do — that everything in their career came to bear on that one film. Recurrent themes, psychologies, all that stuff, comes to bear on this film. So you see it’s playing, but we hope they realize, “Oh, it’s playing with these two other films,” and then realize that some thought went into it.

How much is the programming a matter of personal interest and, perhaps on the other hand — or perhaps not — what people will actually pay for? There must be a balance to strike with good material and what pays the bills. I hope you understand what I’m getting at here.

Oh, I totally… no, no, I totally do. It’s something I think about all the time. It’s the balance between just not being completely selfish and programming stuff that I only want to see, just to keep myself entertained, and not making a complete concession to commercialism. There are certain things I’ll be more interested in than others; there are certain films that Aliza’s going to love more than me and I’ll love more than Aliza. There are films that might seem more familiar to me that I might recognize might not be familiar to the audience, or some that aren’t of as much interest for me.

It’s just a balance the whole way. I have a lot of interest and experience working in cinemas. Audiences have the types of films they like. I’m going halfway with them and halfway with us. That’s the way to think about it. Programming is not just tablets flying down to an audience, and, at the same time, it’s not chasing trends. This is a long-term relationship that I want to have.

And you seem interested in fostering something communal and social, what with the bookstore and bar and restaurant. You don’t even have to see a movie.

That is definitely the hope. And it can be a place where you only go to see a movie. You don’t have to do anything; the space is there if you need it. If someone just wants to rush in, see a movie, and rush home, they can do that easily as well. It’s more about creating a space where all different types of personalities are going to feel comfortable visiting. Sometimes, if I want to see a commercial film in theaters that are showing those a lot, there’s a lot to endure when going to them. That’s not what we’re trying to create; we’re not trying to put obstacles between the audience and their ability to enjoy a film. I really like the idea that someone’s going to come here when they’re five, and come here when they’re fifteen, and come here when they’re twenty-five. That’s the goal.

How do you decide what charges out of the gate, programming-wise? After a while, you’re no longer the new kid on the block, but are ingrained in the repertory system. So if you want that 5-to-15-to-25 relationship, what does it mean to seem fresh and make yourself an established part of the scene? Which is to become “just” a place one can visit for a good experience.

The sense is to work yourself into the film culture in the sense that you’re a trusted entity, that you’re welcomed and standards — in terms of exhibition and presentation and access — doesn’t change. That’s less about programming and more about space. Someone who comes here when they’re five or twenty-five or fifty-five is still finding that the environment meets their needs, they feel comfortable here, and it still feels alive. It doesn’t feel like it’s past its days or whatever. In terms of programming: you never run out of stuff. There’s always something new, and I don’t just mean “new” film. There’s something new to be discovered.

So in terms of keeping a momentum going and keeping an interest… well, there’s interest in us now because we are the new kid on the block. That’s going to happen even if we were showing shit movies. People are like, “Wow, it’s a new place; they built it. That’s weird and interesting and unusual.” We want to keep that interest level on that aspect of it — however, this is what’s driving it. [Points to calendar] As long as we’re energized and we think the audience is energized, we’re not going to have to show bad stuff. There are more films out there than we’ll ever be able to see. We’ve just got to dive in.

Are you ever at the supermarket and find yourself thinking, “You know, this director hasn’t been given a retrospect in some time,” and then an idea pops in your head?

Yeah. I mean, not in the supermarkets, but other stores. I don’t really spend a lot of time in the supermarket. [Laughs] But yes, 100% — that is exactly how it happens. It is just like that. And that’s what’s exciting about it. Watching other movies, certainly. I find the most fertile time is when you’re watching a movie — when you’re in a movie theater — and you see something; you make a connection. It’s just about immersing yourself in films, and not just watching them — reading about them, too. It’s a great pleasure, reading about them. I never get tired of reading about films.

This is just a very basic question, but I’d like to hear more about the process of obtaining a film print — where you go, who you contact, and so on.

It really depends on what film we’re looking for. It is something that’s changed quite a bit in the decade that I’ve been doing this; there are so many variables. Should we just pick something out of the air?

Let me think of one. All right: what about Goodbye, Dragon Inn?

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is a film that, when it was released in the United States in the 2000s, had a distributor; it played around. There were prints, because it was pre-DCP. That company went out of business, so then it becomes a search for who holds the rights, who can clear the rights, and, if no one in America has the rights anymore, who are they with? And then if there’s a print to be found. In this case, the trail really started with Tsai, who Aliza knows, and that led us to the rights, and it also led us to the print. Sometimes, like Matinee and An American Werewolf in London… those are Universal. You call Universal; they book it to you. It’s very simple, because they have the rights and they have the prints. High School is owned by Frederick Wiseman’s company, and I knew that the Library of Congress had just made new prints. So I spoke to my friend, Karen, who works at Wiseman’s office, and I spoke to the Library of Congress to see when they were working on it.

The players are Hollywood studios, small distributors, rights holders — who can be filmmaker themselves or estates — and then there’s print sources, which can be, again, from a distributor or studio or rights holder or an archive in America or a national archive. I mean, there are just a million variations. But that’s part of it, you know? And then you run after those. For the Eustache films, you clear the rights. There are no American rights holders, so you clear the rights with those in France, and put it together through a variety of sources — different archives, or the cultural services of the French Embassy, which maintains a very rich archive of French films. So we can get it through a government organization. Not all countries have that. They might have national archives, but not necessarily distribution prints.

You just sort of figure these things out. So we want to show Daybreak Express, a five-minute short by D.A. Pennebaker. So I call his office and they say, “Okay, they have prints, but we don’t know what condition they’re in.” So I say, “Send me two. We’ll test them and see which one’s good.” That came today, via messenger, from 96th street. [Points] I’m pointing there, in the direction of 96th street.

So there are acts of generosity.

By them? Yeah. Well, we’re going to pay for it, but the idea is, that’s a perfect example. The rights to the Pennebaker films — the majority of them — reside with Pennebaker Hegedus Films. Pennebaker Hegedus Films is in New York. They also have a really active office run by Pennebaker’s son, Frazer. They keep the prints there. After enough years of working with them, you just know that. So if I was to call up another documentary filmmaker that I’d never worked with before, I don’t know where their stuff might be — but, after years of working with Pennebaker, I know they keep them right in their office. You just remember those things, also.

People are excited by the dedication to film formats, be it 8 or 35 or 70mm.

It’s only 8 and 70.

I see.

That’s going to be hard, I know, but I think we can do it. We’ll see what happens. It’s going to be 8 projected inside of 70. We’ll see how that goes.

I’m not an expert, but… well, I’ll leave that up to you. Anyway, if you’re hoping to show something but the print is hard to find or looks terrible, and a good DCP exists, what do you do?

It’s a situation. You have to make the decision. How much do we want to show the film? How familiar are people with the film? This came up on our first calendar. We wanted to show The Last Picture Show, and it was made clear to us that, in order to show that film, we have to show the new DCP restoration. The rights holders were very adamant about us wanting to show that. We thought about it and said, “Okay, we’ll go for it. We’ll go for it and see how the audience reacts.” Now, it wasn’t our first choice to book it; we would have liked to show a print. But there’s no reason to go to war over it, and it was made clear to us that this was a company that was also booking us 35mm prints of other titles. It’s not like they have a resistance to it.

Our preference is definitely towards 35mm, but it depends on the situation. But if we have a preference, it’s for 35mm. We’ve designed both houses with changeover 35mm projection. This room is fucking cluttered with 35mm prints right now. This is what is of interest to us. So, yeah, that’s the direction for sure. But to show a DCP of The Last Picture Show for one or two shows? It’s fine. We’re maybe not as interested in doing a week-long run of a DCP. The films that we’re doing week-long runs of on our first calendar — Student Nurses, High School, Hospital, Titicut Follies — are new 35mm prints. So that’s our feeling. Sidewalk Stories is a DCP, but it was shot on 16 and restored and that’s the best way to see it at this moment.

I want to ask about your series, A-Z. It’s so all-encompassing that I wonder if it’s just you and Aliza Ma making the decisions, or if other members of the office contribute.

Aliza and I are the programmers, but I do talk to Michael and Michael and Alex and people here enough to know what they dig. So when we were putting this together, everyone said, “Age of Innocence!” And I said, “All right. I love Age of Innocence.” If Aliza hadn’t been so in love with it, or… I just know. It’s not Michael or Michael or Alex suggesting so much as understanding. If I was left to my own devices and I had to pick one Scorsese movie, I’d show Color of Money. I love that fucking movie; I’ve seen it fifteen times. But Aliza and I are coming to it while feeling very passionate about certain things. Madeline Anderson is someone who’s very important to me and is not as well-known. There’s no debate about doing the Kenneth Anger films.

It’s funny — here’s a perfect example. We had already gone really deep in programming, and I came in one Monday and said to Koresky — because we had already mocked this program up — “I’ve got some bad news: I want to add in something.” He said, “You can’t. We’re going to press.” I said, “It’s The Beguiled.” He said, “Well, okay — if it’s The Beguiled, then we can hold it.” Because he just loved that movie. Boarding Gate is maybe a surprising choice for Assayas, but when Aliza and I talked about it… I mean, I love Cold Water. But we were like, “There’s something special about this one,” and it’s one that’s not seen often enough. So I think it’s a good mix.

You have Chelsea Girls, which could be an event just because of its rarity.

It’s one of the greatest movies ever made. There’s just no doubt about that. There are films that some might not know well, but they’re masterpieces. And there’s the self-imposed rule of one-per-filmmaker. So Equinox Flower is the film that’s representing Ozu.

That’s surprising.

Do you know it?

I do, and I like it, but I wouldn’t think to peg that as “the one” in a cinematic history.

No, no, yeah, but the thing was, that was instinctive for Aliza. We were thinking about Ozu, and, for me, I could do Tokyo Story or so many different ones. Aliza went with Equinox Flower, and in terms of being definitive about it, we said, “Okay, that’s the one.” And then when we were thinking about Polanski, I thought, “Fuck. Frantic. How fucking good is Frantic?” So it’s about a passion, too. No one’s seen some of these, but they’re masterpieces. I think that’s the governing thing. I love Once Upon a Time in the West and A Fistful of Dollars, but when I thought of Leone, I saw Duck, You Sucker! and went, “That’s the one. That’s just the one.”

You have this Fassbinder series, and, on the site, we like to post lists of directors’ favorite movies. That was one of them. To see a screening selection of those is so exciting.

And it’ll probably be the first time any of us have seen The Red Snowball Tree.

I have to search for clips from films, and —

You couldn’t find anything. If anyone shows up to that screening, myself included, who has seen the film before, I’ll be very impressed. That’s very exciting. Every single person in that theater will probably be seeing it for the first time. How cool is that? And us included. Yeah, the whole series was just a ruse to find an excuse to show The Red Snowball Tree.

That is very elaborate. Between that and the 8-70 dichotomy… a lot of things here are going to surprise people.

I know. Isn’t that weird? The Red Snowball Tree is the one film we’re going to show that’s not 8-in-70.

Metrograph will open on Friday, March 4. See more details on their official site.