While remakes are no stranger to the land of Hollywood and abroad, rare is the case when a filmmaker decides to provide a new take on their earlier work. Warranted or not, there’s a myriad of reasons that go into the decision, and, with the latest example arriving in theaters this week, we’re here to provide one with a handful of notable examples. Check out our rundown below, which contains both theatrical remakes and the jump from shorts to feature-length films. If you want to see more notable remakes, check out our list of The 10 Best American Remakes of Foreign Films.

Cecil B. DeMille // The Ten Commandments (1923) and The Ten Commandments (1956)

With a 33-year gap between these biblical tales, there are clear reasons why Cecil B. DeMille revisited the story of Moses with The Ten Commandments. His first go-round in 1923 was a silent effort, and one that actually only featured a portion of the biblical leader’s story, with the last two-thirds dedicated to seeing the commandments play out in a then-modern setting. While it was a commercial success, his follow-up (and the final film of his career) would provide the landmark entry most of us know today. Led by Charlton Heston, his 1956 version (which features some very familiar sequences and sets from the original) is one of the most-seen films of all-time, taking in an almighty sum of (adjusted for inflation) over $1 billion. – Jordan R.

Michael Haneke // Funny Games (1997) and Funny Games (2007)

A capsule on the first film copied and, then, passed off as a capsule on the second (with maybe an extra comma or two) would almost suffice, though even these to-the-point similarities do not stop yours truly from being more inclined toward Haneke’s original iteration — not only for the more-effective presence of lesser-known stars, but on account of a more decisive message. When brought to American shores a few years back, its refocused criticisms of what was now big in the horror genre — you know, the Hostel and Saw set — felt a little old hat, somehow weighing down the precise formalism of what’s nearly an exact replication. (Unless you want to indulge in the recent horror sensations he chose to mock, which is your own baggage.) – Nick N.

Alfred Hitchcock // The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

With over fifty feature-length films to his name, Alfred Hitchcock revisited many similar themes in his thrillers, but he only remade one of his earlier works a single time. The Man Who Knew Too Much, first arriving in black-and-white in 1934 — and, then, with a bigger budget and Technicolor VistaVision lens in 1956 — tracks a family who unknowingly become involved in an assassination plot and find their child missing. They both feature a rousing climax (quite literally, in the musical sense), but differences can also be found in the gender roles of our lead couples and their responses to the kidnapping — regardless, both approaches resulted in worldwide hits for The Master of Suspense. – Jordan R.

Michael Mann // L.A. Takedown (1989) and Heat (1995)

In the midst of the success of his television show Miami Vice, budding crime auteur Michael Mann had an ambitious, 180-page cops-and-robbers epic that he was struggling to get off the ground. As a solution, he cut the script down to 100 pages and contained the action to Detective Vincent Hanna (Scott Plank) surveying a crew of ruthless thieves led by Patrick McLaren (Alex McArthur), as well as the shootout that occurs after the robbery takes place. It aired on NBC in 1989 as L.A. Takedown to middling reviews. Six years and many millions of dollars later, the original script would become a crime epic, Heat, starring two of film’s greatest actors in the lead roles. – Dan M.

Hideo Nakata // Ringu 2 (1999) and The Ring 2 (2005)

Gore Verbinski translated Ringu into the first J-Horror remake, and the film left audiences hungry for more vengeful spirits. Five years after the original director Hideo Nakata helmed his own sequel, he was hired to reiterate the tale of a haunted videocassette for The Ring 2. His American debut opened to bad reviews and was soon forgotten (save for the viewers who remember its terrible CGI deer), but the flop didn’t stop Nakata from continuing as a successful genre filmmaker in his native country. – Amanda W.

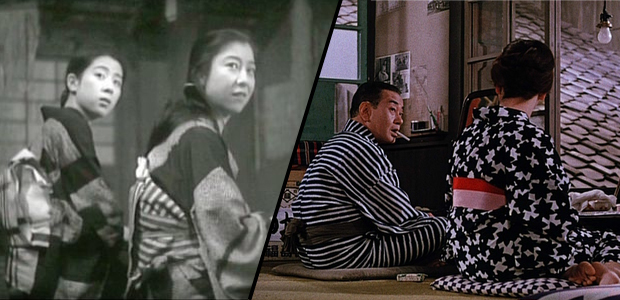

Yasujiro Ozu // A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) and Floating Weeds (1959) & I Was Born, But… (1932) and Good Morning (1959)

I Was Born, But… and A Story of Floating Weeds: two silent, black-and-white Ozu pictures revived, in 1959, as (respectively) the color-splashed talkies Good Morning and Floating Weeds. To watch an original and its redux within any relative proximity is to see the evolution of both a film artist and storyteller, one who’d grown more economical (though these films aren’t exactly The Hobbit in terms of narrative flab) and expressive, the latter accounted for by absolutely astounding implementations of color; Good Morning particularly stands out, feeling akin to seeing the dreams of Born’s central characters played out with vivid life on the screen. While there’s enough to marvel at, knowing these selections are no more than his second and third films in the format, one need not risk forgetting the achingly true-to-life stories at their cores. – Nick N.

Ken Scott // Starbuck (2011) and Delivery Man (2013)

Ken Scott’s remake of his small, cluttered Starbuck is a curious case; adapted essentially from the same screenplay, Delivery Man features restrained, heartfelt performance by Vince Vaughn, who is a clean-cut slacker compared to the scruffy Patrick Huard (the original David Wozniak, a.k.a Starbuck), seemingly a metaphor for just how different these films are. Scott wisely embraces the vibe of each city, crafting a portrait of sink-or-swim New York City in Delivery Man that’s wholly different than the way he lenses Montreal. Watching the two side-by-side could make for an interesting discussion in an intro to filmmaking class about the power of place, casting, and directorial vision. Both versions are delightful, although I couldn’t vouch for the other remakes — apparently the Bollywood and French versions, titled Vicky Donor and Fonzy, respectively, beat Scott’s own remake to theaters. – John F.

Paul Thomas Anderson // The Dirk Diggler Story (1988) and Boogie Nights (1997)

The purpose of this list is elevation, not denigration, so let it just be said that, in progressing from his first real directorial effort, The Dirk Diggler Story (available here), to his mainstream breakthrough, Boogie Nights, Paul Thomas Anderson displayed astounding growth in… well, every department required of a director. Both in spite and because of its amateurish qualities, the 1988 short should only embolden your appreciation of his 1997 epic, which is its own complement. After all, how many things can heighten your enjoyment of Boogie Nights even more? – Nick N.

Wes Anderson // Bottle Rocket (1994) and Bottle Rocket (1996)

Although it didn’t premiere until 1994’s Sundance Film Festival, Wes Anderson shot the 13-minute short Bottle Rocket back in 1992, two years after graduating from the University of Texas at Austin, the place where he first formed a relationship with Owen Wilson. Written by the duo, the original piece (seen here) has a playful, black-and-white aesthetic sensibility closer to early Godard or Jarmusch — certainly not similar to the vibrant unveiling of an auteur that would come in its feature-length version. For also marking one of the few examples where a remake used the same actors as an original, it’s well worth watching to see how the director launched his career. – Jordan R.

Tim Burton // Frankenweenie (1984) and Frankenweenie (2012)

In 1984, Tim Burton directed the charming, retro short Frankenweenie for his then-employer Disney. The company fired him after the film was completed, as they considered the story of a boy and his reanimated dog too scary for kids; Burton followed the termination with a successful feature debut. Nearly thirty years later, the Dark Shadows helmer revisited the live-action work that started his movie career and expanded it into a full length stop-motion film that, while beautifully animated, didn’t quite achieve the fun quirkiness of its predecessor. – Amanda W.

While these ten notable examples represent a variety of remakes in classic Hollywood, international cinema, and the recent landscape — across short and long formats, too — there’s much more in the backlog to discover. When it comes to the short format, before Sam Raimi and Bruce Campbell broke out with The Evil Dead, they helmed the precursor Within the Woods, while South Africa’s Neil Blomkamp made Alive in Joburg with Sharlto Copley before they expanded it in District 9.

We can’t forget George Lucas, whose student film Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB was the basis for his feature debut, THX 1138. In the animation field, Shane Acker turned his Oscar-nominated short 9 into a feature-length project. In terms of indie break-outs, Napoleon Dynamite, Half Nelson, Pariah, and the 2013 festival favorite Short Term 12 all began as short films from directors, while, on the bigger scale, this year’s Mama and This is the End got their start in a smaller format.

But feature-to-feature remakes can’t all be successes. The Pang brothers turned their debut Bangkok Dangerous into the Nicolas Cage-led Hollywood version, while Géla Babluani went from 13 Tzameti to simply 13, which starred Mickey Rourke, Ray Winstone, and Jason Statham, and was a critical & financial disaster. On the flipside, Hollywood gave Takashi Shimizu the chance to remake Ju-On as The Grudge, which translated into a huge box-office hit.

Ole Bornedal also underwent the same treatment, turning his Danish Nattevagten into the Ewan McGregor-led Nightwatch, while Francis Veber used his French crime comedy Les Fugitives as the basis for the Nick Nolte-led Three Fugitives. Jeff Bridges and Kiefer Sutherland starred in George Sluizer‘s The Vanishing, which came from his Dutch thriller Spoorloos. Going back much further, Howard Hawks remade Ball Of Fire only a few years later with 1948’s A Song Is Born, and Leo McCarey returned to safer territory for one of his final films, the Cary Grant-led An Affair to Remember, which came from his original Love Affair.

What versions of the above works do you prefer? What remakes were warranted?